The vindication of Gaëtan Dugas: How scientists finally vanquished the 'Patient Zero' myth

Dugas died in 1984 at the age of 31 from kidney failure from Aids-related infections.

On 1 December, people around the globe will mark World Aids Day. This year's event is particularly poignant as it is the year the man who was widely blamed for bringing HIV to the US was finally vindicated.

Throughout the 1970s, little was known about HIV/Aids – cases had been increasingly emerging in the West and understanding of what it was and how it spread was lacking. At this time, Gaëtan Dugas was a Canadian flight attendant working for Air Canada.

The first case of Aids was officially recognised in the US was Ken Horne, who was diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma in April 1980. By the end of 1981, 270 cases had been reported among gay men. Of these, 121 had died.

In 1982, a cluster of cases in California suggested the cause of the as-of-then unidentified immune deficiency was sexual. In September that year, the Center for Disease Control first used the term Aids (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). It was described as: "A disease at least moderately predictive of a defect in cell mediated immunity, occurring in a person with no known case for diminished resistance to that disease."

The following year, the World Health Organization held its first ever meeting to assess the global scale of Aids and to start international surveillance.

It was also the year the first AIDS Information Forum was held in Vancouver. Dugas was one of the speakers at the event.

During the conference, he asked a panel of experts questions about things for which there were no answers to. He asked if there was any reason to fear people with Aids or Aids symptoms. "What is the warning you give to people? It seems like there's kind of a fear towards those people here ... But you should, you know, not necessarily fear those people." He was advised that you should inform a partner if you had Aids, and told there is no vaccine and there is no test for Aids.

Dugas died in 1984 at the age of 31 from kidney failure from Aids-related infections.

How did he become 'Patient Zero'?

In 1984, the CDC published the study 'Cluster of cases of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome'. In it, experts were exploring the possibility that Aids was sexually transmitted. They found there was a correlation, with the sexual partners of people with Aids going on to be diagnosed.

In the study, they also looked at the geographical locations of the patients. "Four of the patients from southern California had contact with a non-Californian Aids patient, who was also the sexual partner of four Aids patients from New York City. Ultimately, 40 patients in 10 cities were linked by sexual contact. On the basis of six pairs of patients, a mean latency period of 10.5 months (range seven to 14 months) is estimated between sexual contact and symptom onset. The finding of a cluster of Aids patients linked by sexual contact is consistent with the hypothesis that Aids is caused by an infectious agent."

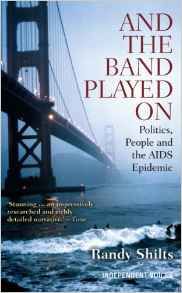

This did not lead Dugas to be identified as bringing HIV to North America. Three years later, gay journalist Randy Shilts published his book And the Band Played On. In it, he claimed to have identified Patient Zero – or the original carrier who brought Aids into the country.

He named this person as Dugas and the mainstream media rolled with it. They highlighted his promiscuous lifestyle and public perception of the disease led to widespread stigma. He became the face of Aids.

Speaking to NBC earlier this year, HIV/Aids activist Kelsey Louie said: "That created the stigma that now exists, and that has existed for the past 35 years around HIV and Aids – identifying gay behaviour and gay sex as the leading cause for the spread of HIV and Aids."

Fellow activist Eric Sawyer added: "It stigmatised gay men, as I said, like vectors of infection that would be responsible for spreading HIV and other horrible diseases, and that they should be avoided at all costs," he said. "It created a hysteria, which resulted in gay men being fired from their jobs, evicted from apartments, denied public accommodations and denied health insurance."

What Shilts had failed to realise was that in the CDC study, Dugas had been referred to by the scientists as patient "O" to signify he came from someone outside of California. But even after the mistake was clarified, the damage was done.

Writing in the journal Nature earlier this year, scientists looked back at the misidentification. "As investigators numbered the cluster cases by date of symptom onset, the letter "O" was misinterpreted as the number "0", and the non-Californian Aids patient entered the literature with that title," they wrote. "Although the authors of the cluster study repeatedly maintained that Patient 0 was probably not the 'source' of Aids for the cluster or the wider US epidemic, many people have subsequently employed the term 'patient zero' to denote an original or primary case, and many still believe the story today."

Final vindication

In the decades that followed, our understanding of HIV and Aids increased vastly – including how is spread across the globe. Scientists believe it originated in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, in the 1920s. The HIV virus was able to spread very effectively because of a number of factors, including urban growth, railway links and changes to the sex trade.

To finally show how HIV got to North America, the team, led by Michael Worobey of the University of Arizona, analysed Dugas' HIV genome to see where it came from: "We recovered the complete HIV-1 genome of Patient 0 and examined it against the backdrop provided by the 1970s sequences," they wrote.

They recovered eight samples from New York and San Francisco dating back to 1978 and 1979. Findings showed the virus had spread from the Caribbean to New York before it emerged across the rest of the US and Canada. The diversity of the virus also showed it must have been circulating long before it was recognised in the early 1980s.

"We recovered the HIV-1 genome from the individual known as 'Patient 0' and found neither biological nor historical evidence that he was the primary case in the US or for subtype B as a whole," they conclude.

Following its publication, many argued that Dugas had been exonerated long before and that there was no need to reiterate the perpetual myth. Commenting for the Guardian at the time, Steven W Thrasher summed up: "Let's allow Dugas's most recent exoneration to be his final one, and let's take this chance to retire the idea of the HIV/Aids scapegoat. Let's stop the shame and blame, so that we may move on the challenge of tackling the real, treatable and preventable ways HIV is transmitted."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.