Why this Italian family can't feel pain from burns and fractured bones

The cause of their insensitivity to pain goes all the way to their genes.

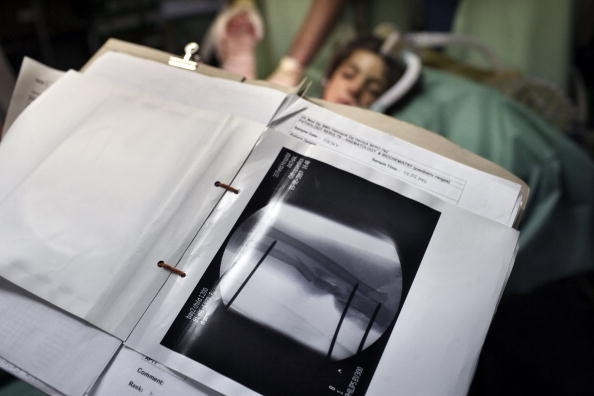

A group of British scientists has finally decoded why six members of an Italian family cannot feel pain even after suffering from burns and fractured bones.

The idea of not feeling pain may sound like a great superpower, but the fact is growing that without understanding the sensation of touching a hot stovetop or having a bone fractured could make people vulnerable to injuries. This is what three generations of the Marsili family have been dealing with.

"The members of this family can burn themselves or experience pain-free bone fractures without feeling any pain," said study lead James Cox from University College London. "But they have a normal intraepidermal nerve fibre density, which means their nerves are all there, they're just not working how they should be."

However, after analysing their DNA and comparing those results with mice models, researchers found the cause of their lack of pain – mutation in a gene dubbed ZFHX2.

Typically, this gene plays a role in how pain signals are interpreted by nerves and relayed to our brains and the research team believes further studies revolving around it could lead to the development of better pain suppressing drugs.

First, the researchers poked the family members at soft spots, asked them to touch hot surfaces and dip their hands in cold water. They then conducted DNA analysis of their blood samples, which revealed a novel mutation in ZFHX2.

As the altered gene was found in each family member suffering from the condition, the researchers decided to put their theory to test.

They tested mice modified with the same mutated version of the gene and noted pretty similar behaviour. The animals demonstrated difficulty in sensing hot and cold, something that confirmed ZFHX2 is indeed responsible for causing lack of pain for three generations of the Marsili family.

Now, the researchers believe further studies around this and other similar genes could offer them crucial insights to develop better drugs to reduce chronic pain.

"By identifying this mutation and clarifying that it contributes to the family's pain insensitivity, we have opened up a whole new route to drug discovery for pain relief," says study co-author Anna Maria Aloisi.

"With more research to understand exactly how the mutation impacts pain sensitivity, and to see what other genes might be involved, we could identify novel targets for drug development".

The results of the study were published in the journal Brain.