9/11 Anniversary: Airport Security is 'Window Dressing Dogged by Political Correctness'

Airport security is failing, with much of the current measures in place largely serving as window dressing that distracts from staff carrying out their jobs effectively, an expert has said.

Thirteen years on from the 9/11 terror attacks on the Twin Towers in New York, the perceived threat of an attack on airports or airplanes is still high.

Earlier this year, the British government announced it was stepping up security measures at airports, with passengers asked to ensure all electronic devices taken on board a flight are fully charged. The Department for Transport said the measures would impact "some routes", without specifying which and warned all international travellers to be prepared.

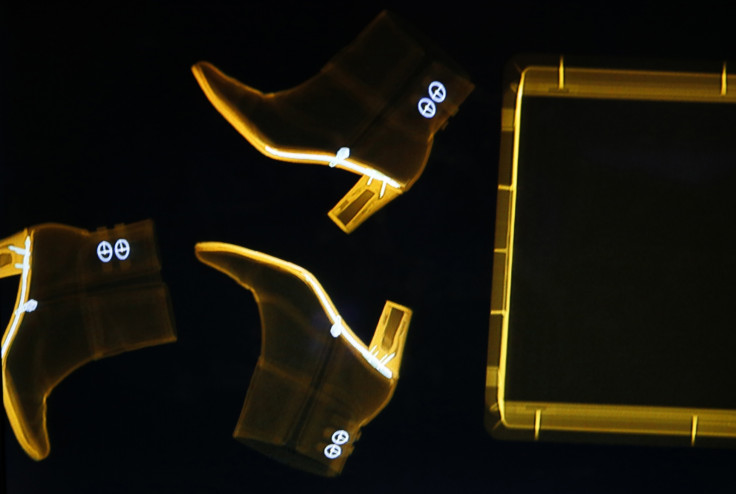

Like the process of taking off your shoes and belts to go through an x-ray machine, these measures affect all passengers – whether people are going on holiday, a business trip or planning an attack on board a plane.

"I've long felt that a lot of airport security is theatre – and good theatre," said Philip Baum, editor of Aviation Security International. "It's certainly had a deterrent effect otherwise we'd be witnessing far more attacks than we already are. How effective is the security system? It varies from location to location."

Baum said there are three main problems with airport security – that we are overly concerned with political correctness, too reliant on technology and that there is a lack of recognition on the wide range of threats not necessarily related to terrorism.

"We have this faith in 1960s/70s base technologies - x-rays and bomb detection - to identify threats if and when people go through the checkpoint. The number of stowaways shows that people don't always go through the checkpoints if they don't want to be identified. There's a lot of window dressing there, there's a lot of theatre, but huge loopholes."

Passport staff miss 14% of fake IDs

Echoing the problems with relying on checkpoints, David White, postdoctoral research fellow at UNSW Australia, recently found that on average, passport control officers let through one in seven people using fake documents.

While it has long been known people are bad at recognising strangers' faces, the study was the first to show how passport control officers perform at the task. While the average officer stopped 86% of fake IDs, some had a 100% success rate on the task – suggesting some people are better at identifying strangers' faces than others.

"We found those individual differences are actually quite stable, suggesting there is a latent ability. The implication of that is that we would expect to see the same result anywhere that staff aren't selected on the basis of that ability." He added that for these specialist roles, the ability to recognise a face "is key". However, staff are not picked on their facial recognition abilities.

Baum said that treating every passenger the same is a mistake that does not happen in other areas of security. He said that when passengers arrive, immigration and customs officers do not treat all passengers equally – they look out for those behaving suspiciously, and depending on where you have arrived from, you must join the specific immigration queue.

"At airport terminals you've got police officers looking for victims of human trafficking and traffickers because they're looking for certain characteristics that are associated with carrying out that type of crime or being victims of that type of crime. When it comes to airport security, somehow we dumb it all down and say everybody's got to go through exactly the same process."

He said the government justifies the process by saying the risks are much higher at an airport: "I will buy that argument but, on that basis, why are we paying airport screeners a fraction of what we pay customs officers? If it's so much more serious, then why aren't we deploying the best people to do it?"

The issue of racial profiling

After the 9/11 attacks, racial profiling at airports rose significantly, with many people who appeared to be Muslim or of Middle Eastern descent being stopped by officials. The practice – which was and is particularly prevalent in the US – has been widely condemned, despite a 2010 USA Today poll finding most Americans supported it.

As well as being highly unethical, researchers have found that racial profiling is no more effective than random profiling because terrorists are vastly outnumbered by regular passengers. Another study said it was less effective – terrorists do not always fit a racial profile.

"I'm a passionate believer in profiling and when I say profiling I'm not talking about racial profiling, I'm talking about behavioural analysis," Baum said. "We live in this type of society where we have to be politically correct, where any discussion of the word profiling somehow gets taken down the route of 'oh you're going to discriminate against people we've got to treat everybody fairly', rather than actually recognising that – as other security services recognise – there is nothing fair about terrorism and there is nothing fair about criminal activity."

Previous research has also shown that racial profiling poses a specific problem at airports – especially in light of White's study about poor facial recognition. People from one race have more difficulty recognising people from different races in comparison to their own.

"It's one of those things that people worry it's controversial to say that but in fact it's just a product of a perception," White said. "We are just less familiar with the variation in faces of other races due to the fact that it's not part of our visual diet, so yes people find it more difficult to discriminate from ethnicities other than their own.

"I think [racial profiling] happens for other reasons than the difficulty we have with recognising faces of other races, but I guess it would exacerbate the problem if you think your perception of identifying people of another race is poor."

Baum added: "I get concerned if people are suddenly going to focus on young Asian males aged between 18 and 40 years of age. Because then we're only starting to think about the one type of threat. We also forget the fact that you don't necessarily have to be Asian to join groups such as Isis, you don't have to be male to become a jihadist.

"The threat of the unruly passenger, who is more likely to be a young British male or female going on a stag weekend to Ibiza, is much higher."

What's the solution?

Baum said that much of what people go through at airport security is unnecessary and is actually "extremely poor security": "So many people have to take their belts off, so many people have to take their shoes off, so many people to take their laptops out of their bags, so many people to limit the amount of liquids they can take on board ... all this does is to serve as a distraction to the security guard from actually identifying who might be a threat. Most of the people who have to go through this procedure are obviously not a threat.

"Ultimately we need to derive an intelligent response to the threats that we face.

"We need to look at people and we need to decide based on how they appear on the day that they're flying whether or not they could pose a threat. And when I say pose a threat I'm not talking about terrorists, I'm talking about if they could potentially commit a criminal act on board an aircraft. And that can be anything from a suicidal terrorist to a drunk, unruly passenger.

"The problem is that we've turned aviation security into a counter terrorist operation, which it's not and it shouldn't be."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.