Aftab Bahadur Masih: Pakistan just hanged an innocent man

Record keeping is not a strong point of the Pakistani bureaucracy, but it seems probable that, when he was hanged at 04.30am local time last night, Aftab Bahadur became the 150<sup>th victim of the Pakistani hangman's noose since the moratorium was lifted roughly 150 days ago.

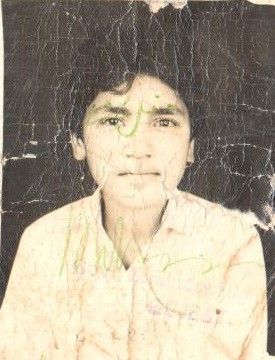

IBTimes UK broke the story just five days ago, and it is fitting that I write some semblance of an obituary, now that Aftab has met a gruesome death in the dark of the night in Lahore Central Jail.

In some ways his plight was typical. For example, he was too poor to hire competent counsel. He was too poor to avoid torture by the police. He did not have the £320 bribe that the police demanded to let him go.

Until we (Reprieve) and the Justice Project Pakistan recently jumped in to provide pro bono legal help, he had not had a lawyer at all for almost two decades. That is as it has ever been: capital punishment means those without the capital get the punishment.

He was too young and uneducated to defend himself. Aged just 15 when he was arrested in September 1992, he did not even know that his age disqualified him from the gallows.

So he did not press his court appointed lawyer to raise the point and the courts would later say he had missed his chance. But the best estimate is that roughly 1,099 of the 8,261 prisoners on Pakistan's death row may be juveniles, so again he was an archetypal victim.

He would have had a difficult time defending himself anyway, as he was tried in the special courts – the precursor to the anti-terror courts (ATC) – where there are fewer protections against evidence elicited by torture, and where the appellate process is radically curtailed.

But then that is not so unique: our recent study shows that more than 85% of those tried in the ATC had nothing even plausibly to do with terrorism. It is just a pretext, founded on fear, to strip away the limited due process that might otherwise protect someone like Aftab. And it is not unique to Pakistan, as I can attest after 34 visits to Guantanamo Bay.

It is, perhaps, ironic that he was tried in what is called the 'speedy trial courts', since Aftab spent more than half of his life (over 22 of his 38 years) on death row. Again that is not so rare.

We already have clear data for 112 of the first 150 people who have been hanged. Of these, just six were executed within ten years, which would be roughly how long they might have served on a life sentence. The other 106 spent far longer with the Sword of Damocles hanging over them - up to 24 years - before Pakistan finally got around to killing them.

Finally, the fact that Aftab was hanged for a crime he did not commit – the tragic death of Sabiha Bari and her two sons on September 5, 1992 – also hardly sets his case apart. After all, on one trip to Pakistan I had coffee with a judge who was presiding over a capital trial. I asked him how certain he had to be before condemning someone to the gallows. He said: Maybe sixty percent sure.

I pointed out that this meant he was aiming to be wrong four times in ten, and if he aimed low, he would surely miss. His reply: The evidence in Pakistani courts is so unreliable that if he held the prosecution to a higher standard he could never convict anyone.

Ultimately, however, there could hardly be a less appropriate victim of the hangman's noose than Aftab. In the past week, the 'eyewitness' to the murder recanted, saying that he lied when he said Aftab did it. Indeed, he said he was not even there, so he did not see anything.

Meanwhile the other 'witness' - co-accused Ghulam - said, to his credit, that he could not go to his own maker without clearing Aftab. He had, he said, been forced to implicate Aftab by the police, and he now wanted to make clear that it was a lie, and Aftab was innocent.

As the seconds ticked by to 04.30 am, a relative of the victims appeared and, hurriedly and long past the Eleventh Hour, insisted he wanted to pardon one of the two men waiting to die: one, but not the other. So who would live, and who would have a reprieve? Would it be Ghulam, the adult who insisted he had falsely implicated Aftab? Or would it be Aftab, then a 15 year old child, who had clearly had nothing to do with the crime?

And so it was that Ghulam was spared. Aftab made that last walk to the gallows, where he wept, and insisted that he was an innocent man. Then the executioner placed the noose around his neck and pulled the lever, hurling him down to twist and dangle until he was dead.

Clive Stafford Smith is the Director of the legal action charity Reprieve, at www.reprieve.org.uk

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.