Ancient Greece: scientists crack DNA sequence from 'cradle of Western civilisation' for first time

The findings reveal origins of the Minoan people of Crete, home to the legend of the Minotaur.

Ancient DNA from Bronze Age Greek human remains has been sequenced for the first time. The findings could transform historical interpretations of the two main cultures that dominated pre-Classical Greece.

Greece at that time is often known as the cradle of western civilisation. It was home to the first literate societies in Europe and the world's first democracy. The ancient Greeks invented libraries, the Olympics and even lighthouses.

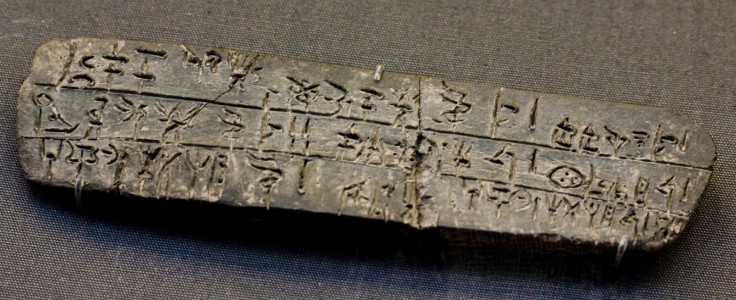

The two cultures that gave rise to all this were the Minoans, who lived on the island of Crete, and the Mycenaeans, who occupied the mainland. Swathes of history books have been written about these people. But a study in the journal Nature reporting the results of DNA sequencing of these individuals has yielded a few surprises.

Researchers studied the bodies of 19 Greeks who lived between 2900 and 1200 BCE has yielded a few surprises. These included Minoans, Mycenaeans and other people of south-west Anatolia. This was compared with data on 3,000 other individuals, ancient and modern, to put the relationship between the groups into perspective.

"We wanted to determine if the people who made up the Minoan and Mycenaean populations were actually genetically distinct or not. How were they related to each other? Who were their ancestors? And how are modern Greeks related to them?" said study author Johannes Krause, director of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

The Minoans were often thought to have come from a distant culture, arriving on Crete around 2600 BCE, quickly making their mark in terms of art, literature and architecture. Minoan Crete was the home to many legends, not least that of the Minotaur and the labyrinth.

In fact, the DNA of 10 Minoans reveals that they were locals, descended from the Neolithic farmers of western Anatolia and the Aegean. Far from being disruptive outsiders, they had deep roots in Greece stretching back for generations.

The Mycenaeans of the mainland eventually came to dominate Crete as well as the mainland and surrounding islands. They were in fact very closely related to the Minoans they succeeded, DNA from the bodies of four Mycenaeans indicates. Both shared about 75% of their ancestry from Neolithic farmers, with some additional elements from Iran and the Caucasus.

However, the Mycenaeans also had traces of Bronze Age ancestry from the Eurasian steppe that was absent in the Minoans. This could mark a previously unknown migration event from the northern steppe that reached mainland Greece but not as far as Crete.

"It is remarkable how persistent the ancestry of the first European farmers is in Greece and other parts of southern Europe, but this does not mean that the populations there were completely isolated," said Iosif Lazaridis of Harvard Medical School, lead author of the study.

"There were at least two additional migrations in the Aegean before the time of the Minoans and Mycenaeans and some additional admixture later."

Identifying precise timings and the extent of these migrations will be among the scientists' questions as they pursue this line of research, building up a clearer picture of the origins of Greek civilisation.

"The Greeks have always been a 'work in progress' in which layers of migration through the ages added to, but did not erase the genetic heritage of the Bronze Age populations."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.