Chancellor Angela Merkel Will Both Win and Lose the German Election

When you go to Berlin, you cannot escape the history of conflict.

The legacy is everywhere, from a banal car park over the ruins of Adolf Hitler's bunker to Checkpoint Charlie where American and Soviet tanks faced each other down.

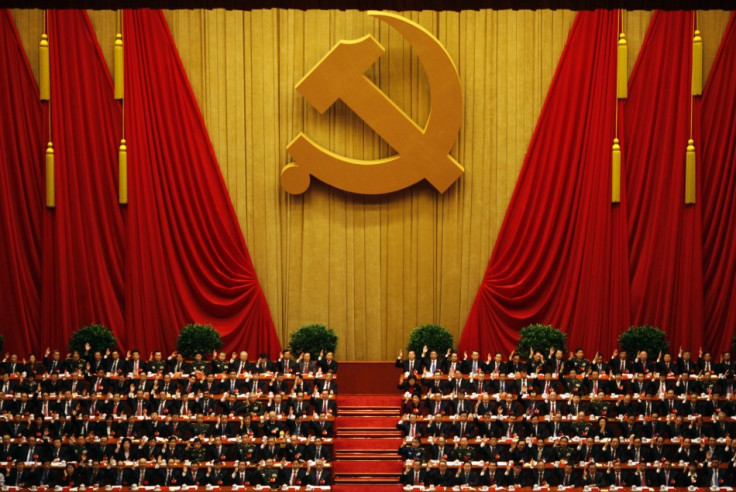

The old headquarters of the Stasi is a monument to communist paranoia and the Berlin Wall is a reminder of how the Eastern bloc was frozen out of civilisation by Soviet imperialism.

Berlin's many memorials represent failed answers to the timeless question of Germany's role in Europe.

All eyes were centred on Germany when it reunified in 1990 and now they are again with national elections on 22 September that could be decisive in steering Europe's future.

At the centre of speculation about Germany is concern about its power and how it shapes the rest of the continent.

The Iron Chancellor's Aura

Angela Merkel is the dominant politician in Germany.

For the past eight years no political rival has matched her popularity or longevity.

The outside world expects her to win a third term, but the exact composition of the coalition that would emerge from a Merkel victory is hard to predict.

That is where the danger for the eurozone lies.

David Marsh is a former European editor of the Financial Times and is currently chairman of the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum think-tank.

He recently published a book called Europe's Deadlock: How the Euro Crisis Could Be Solved - and Why It Won't Happen, a very sceptical look at the possible direction the European Monetary Union could take.

Coalition Building

Marsh thinks that Merkel has a 90% chance of regaining her chancellorship, but is uncertain about the alliance she might forge.

Merkel's current coalition is a partnership, between her own party, the Conservative Democratic Union (CDU) and the liberal Free Democrats Party (FDP), is not likely to be returned to power.

"A month ago I would've said 90% chance that Merkel will be the chancellor, 60% likelihood that she'll be leading the present coalition and 30% likelihood that she will be leading a grand coalition," says Marsh.

Now he believes that it is "maybe only 50% likely that she will continue the present coalition and maybe 40% likely that there will be a Grand Coalition".

The reason why a Grand Coalition is the most likely option is that support for the FDP has been withering among German voters and the FDP recently lost in Bavaria's regional elections, where they were trounced by Merkel's Bavarian allies, the Christian Social Union (CUS).

Stephen Adams, a partner at London-based political consultancy Global Counsel and an expert on Germany, agrees that a Grand Coalition is the most likely outcome of voting on the 22 September.

However, he thinks that a coalition between the Green Party and Merkel's CDU is the second most likely option after a Grand Coalition between the CDU and the Social Democratic Party (SPD), Germany's main left-wing party.

"I think there is a possibility of a Green-Black Coalition numerically that would probably work. It is not as unlikely as you thought it might have been 10 years ago," says Adams.

"I think the Greens have moved to the right politically. They are much more a party of economically comfortable rural Germany rather than a party of environmental activists."

Nevertheless, a partnership between Merkel and Greens is probably not on the table at the moment.

"I still think that the level of compatibility is not quite right and that leaves us with the prospect of a Grand Coalition, which would see the SDP in a coalition government with CDU as a junior coalition partner in the same that they did in 2005," says Adams.

"So the numbers look to me like they are pointing at this stage towards another Grand Coalition."

The Paradox of Strength

There is a paradox for Merkel in that she is by far the most popular and effective politician in Germany but under her aura is a fragile political system.

The Germans are becoming increasingly eurosceptic.

This is expressed in Alternative fur Deutschland Party (AfD) that could steal crucial votes from Merkel's current coalition partners, the FDP.

Adams explains the dilemma for Merkel faces.

"If they take four percentage points off the CDU over the week then that potentially is a really serious impact. They won't take 4%, I think, but they could take 2% or 3%," he says.

In many ways Merkel is not nearly as powerful as her image and record suggests and she also knows it.

Merkel and East Germany

At heart Merkel is a pragmatist, Marsh argues, who gives away little and is notorious for taking her time to make decisions.

She is not an impulsive poker player, but rather a chess grandmaster with a brilliant instinct for power but no grand vision about how she wants to use it.

Her ruthlessness and ability to frustrate her adversaries is one of the reasons why she has survived for so long.

The key that unlocks her personality, perspective on Germany in Europe and the way she approaches the sovereign debt crisis is her past in East Germany.

"I think her instincts for ruthlessness and being very cautious and not saying too much was developed under the communist system where saying too much could cost you your job or worse," says Marsh.

The part of the German population who are becoming increasingly Eurosceptic are the East Germans who are reluctant converts to the single currency.

Their sceptical view of continuous bailouts of southern European nations is rooted in their experience of communism.

"Her East German countrymen are pretty antagonistic because they liked the idea of becoming German in a united German state with the D-Mark. They realised the next step was the euro but they are rather reluctant converts," adds Marsh.

That fact weighs heavily on Merkel's mind as she tries to read German attitudes towards further or less European integration.

Her methodical approach to decision making has slowed down any swift response to the debt crisis, according to her fiercest critics.

It will also prevent any resolution in the short term.

Insoluble Conundrum

With scepticism about a banking and fiscal union increasing among Germans, a fragile coalition outcome likely from the German elections and Merkel's cautious approach to Europe, the chances of Germany finding an answer to the Eurozone crisis are slim.

One of the other legacies for Germans apart from communism is that of the Second World War, which is in some ways more painful and controversial.

The tragedy of the monetary union is that it was meant to be an extension of the immediate post-war reconciliation between Germany and all of the nations it conquered.

Unfortunately, it has ended up dividing Europe even more with fierce disputes between debtor nations and creditor nations.

Adams insists that Merkel understands Germany's special obligations to the single currency due to its economic power.

"My sense would be that she has a combination of quite a characteristic German view of Europe for Germans of her generation. She understands that for reasons of economic scale and for no other reasons, Germany has unique obligations in terms of preserving the single currency," he says.

Yet any future direction of Europe will be set by a timetable in Berlin whether others like it or not. The Germans will not be rushed.

"She is a very pragmatic politician who understands that you can lead the German people only at the pace which they are comfortable to travel into further," he reflects.

Although Germans might feel special responsibilities due to past transgressions that does not mean that they are willing to write a blank cheque to Europe.

Delaying Tactics to Fix a Broken Dream

Merkel is only decisive on the issues of banking and fiscal union when she is forced to be by a crisis that has threatened to rip apart the whole monetary union.

She reacts to German public opinion on Europe and does not lead it, according to Marsh.

"On the banking union and a march forward to a more integrated European landscape, she's certainly not terribly persuasive or active in this," he says.

"She's going along with the banking union because she knows that is what the other countries want, but the Germans are slowing that down."

Due to her instinct for power yet lack of vision, it seems that even if Merkel had the power to create a better monetary union after the September elections, she does not have a roadmap.

Merkel's Vagueness

People criticise a lack of German leadership on the eurozone crisis. They have a point.

Merkel coins phrases like "we need more Europe" and "if the euro fails then Europe fails" yet she does not lay out what she means by this or what type of union the Germans want in concrete terms, says Marsh.

In her third term, Merkel will come under pressure from the French President Francois Hollande to specify what type of Europe Germany desires.

The problem is that even though Germany is the superpower in the European Union, Germany cannot lead it.

This is not only because of Merkel's pragmatism, but also due to a historical legacy that makes Germans feel uneasy about their power.

"To expect the Germans to just put a lot of money on the table and to bang their fist on the table and to say, 'this is our blueprint for the future' is just complete nonsense," says Marsh.

"Firstly the Germans don't want to do it. Secondly if they did do it, nobody would like it and thirdly it is not going to happen. So why spend our time talking about it?"

Merkel's Legacy and Priorities?

Marsh is pessimistic about the current sustainability of the monetary union and Merkel's ability to make the situation much better from where it is now if she wins.

"All that we can ask for is for the Germans to take a certain amount of responsibility for what is happening in Europe right now and to work with other like-minded countries like Britain and France to try to repair the situation."

Adams is more optimistic about how Merkel will be seen in the future and her influence on the shaping the currency area.

"I think that she will be regarded as having in her own way corralled the German political class behind a response to the eurozone crisis; pulled the German political class into signing up to four major bailouts of other eurozone states; and ultimately ensuring that Berlin signed up to what is at this stage the early form of a banking union and a greater system of fiscal co-ordination," says Adams.

Tragic Prospects

In a sense Angela Merkel, Germany and the eurozone are haunted by the past.

Europeans try to escape the shadows of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin through co-operation, but often come back to them.

The EU is meant to bring prosperity to everyone, with the euro an embodiment of this.

Now, with the most important German election in years unfolding, Germans and their neighbours are again asking fundamental questions about what they want to be.

It is a sombre fact that the fate of Europe will ultimately be decided in a city that the continent's complexities and conflicts have taken root in and been transformed from so many times before: Berlin.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.