Antarctic ice shelves are melting from within as well, making them a lot more fragile says ESA

The "canyons" are 200m deep and 15km across, and run the entire length of the underside of the Dotson ice shelf.

The European Space Agency (ESA) has discovered that large "canyons" are being carved out within Antarctic ice shelves due to the ice melting from inside. While the fact that sheets are getting thinner from the top surface is common knowledge, recent research has shown that the shelves have become a lot more fragile since they are melting from within as well.

This discovery was made after studying data from the CryoSat and Sentinel-1 satellite missions, the space agency said.

Ice shelves are thick bands of ice that surround Antarctica and provide reinforcement for ice sheets on the continent. These shelves extend out into the sea and float on the water, and one of their major roles is to slow down ice sheets in their gradual seaward drift.

However, the ESA points out that there have been a "worrying number of reports" about ice shelves thinning and breaking, like the recent one where a trillion-tonne shelf the size of Manhattan broke off.

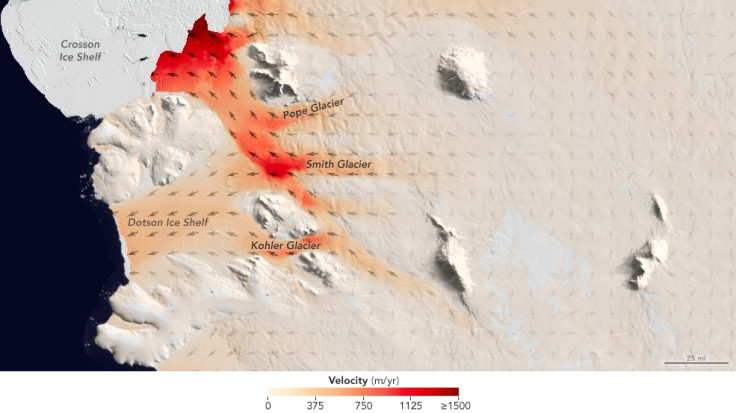

This thinning and breaking of shelves could allow the inland ice to flow faster into the ocean, says the report, which will further add to the rising sea levels.

"Melt from the Dotson ice shelf results in 40 billion tonnes of freshwater being poured into the Southern Ocean every year, and this canyon alone is responsible for the release of four billion tonnes – a significant proportion," said Noel Gourmelen, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh.

He added, "It is the first time that we've been able to see this process in the making and we will now expand our area of interest to the shelves all around Antarctica to see how they are responding."

The inverted canyons along the Dotson ice shelf are 200m deep and 15km across, and run the entire length of the underside of the shelf, Gourmelen said. He added that the rate of melting is increasing by about seven metres a year.

One of the possible explanations provided by the ESA as to how these canyons form is that it is caused by sub-glacial water that drains out from beneath the ice into the sea causing the ocean to stratify – form layers that act as barriers to water mixing – in this case based on temperature. The report says that warmer water collects at the bottom. This water is at 1 deg C.

When cold meltwater from the shelves pours into the ocean, it rises because it is less dense that seawater, but as it rises, it takes the warm water along with it to the upper surface of the sea and causes the underbelly of the shelf to melt as a result.

Another situation that could cause this level of melting is the way in which the ocean circulates under a shelf, the ESA reports. Using the CryoSat to study changes on the surface of the ice shelf and the Copernicus Sentinel-1 to learn how the shelves flow, researchers were able to learn more about the process.

"Revisiting older satellite data, we think that this melt pattern has been taking place for at least the entire 25 years that Earth observation satellites have been recording changes in Antarctica," said Gourmelen.