Asbestos: How drawing pins are killing off UK teachers

Michael Lees has spent 15 years thinking about asbestos in British schools. The 67-year-old artist from Devon has been in its thrall ever since the death of his wife Gina at age 51 in 2000. She suffered from mesothelioma – a form of lung cancer.

Gina worked as a teacher for more than 30 years and Lees now believes she spent much of that time unnecessarily exposed to asbestos in the school building.

Frustrated with the official response to a problem that could potentially lead to the premature death of hundreds if not thousands of teachers across Britain, he founded the Asbestos in Schools group.

Lees went on to conduct research into mesothelioma incidence among UK teachers – he believes it to be the highest in the world – and has found little comfort in his findings.

"Exposure levels are likely to be lower than in 1960s and '70s but the difference is that all this material is now old," he said. "The Asbestos Installation Boards (AIBs), are so deteriorated with age it's therefore likely normal classroom activities can still release asbestos fibres that thousands can still be exposed to, so long as this material is accessible to children."

Worrying trend

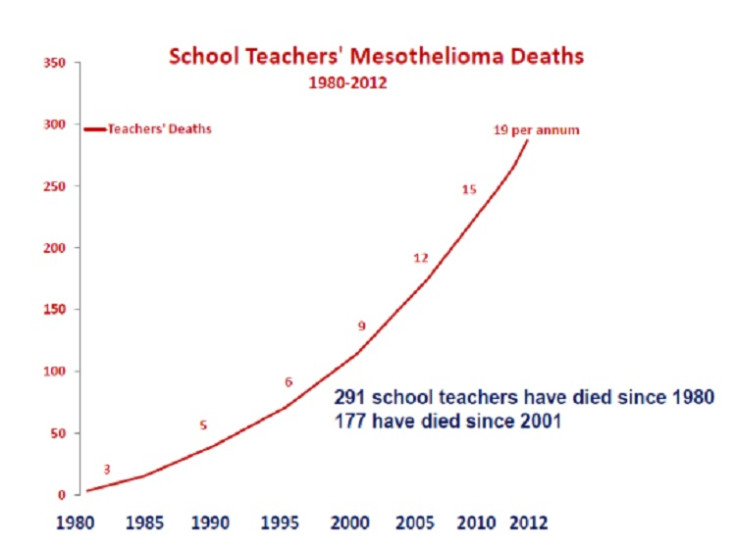

Using HSE figures he obtained via Freedom of Information requests, he found 291 teachers have died from mesothelioma since 1980. Three school teachers died on average each year in the 1980s, which now has risen to 19 a year.

Lees told IBTimes UK: "This is still a very significant problem because the deaths that are occurring now are due to the very long latency of mesothelioma, which can vary between 35 years to 55 years depending on the exposure levels."

In his wife's case, changing art work display boards daily, which was common practice for teachers, was part of her job.

"For each drawing pin, 6,000 fibres are released when you do that. When we took this research to the government advisory committee on science, the so-called Watch committee, they concluded that the breathing zone of the teacher the level is 0.5 fibres per ml of air – that is 50,000 fibres of a breathing zone of the person actually doing it regularly over the course of a day. This can build up to be a significant exposure."

He believes asbestos in schools should not be regarded as a "building legacy problem" that should be ignored. On the contrary, he is now calling on the government to change its policy of leaving asbestos "if it is not disturbed or damaged until a school is demolished" and carry out a national audit to identify schools that are most at risk and contain the most dangerous asbestos, such as AIBs.

"We fully acknowledge the fact there isn't the resources or the money to remove all these AIBs and the asbestos accessible to children," he added. "What we have stated is that children are more at risk so schools should be given priority. Having carried out a national audit, the government could then set priorities. They can make long-term financial forecasts and adopt a strategy so that over the years they have a policy of gradually removing the asbestos and therefore in the long run you will actually solve the problem."

An ongoing problem

On 9 April, a family in Gloucestershire decided to sue a council over the death of Jennifer Barnett, an art teacher. Her husband, Nigel, believes she contracted mesothelioma after years of pinning pupils' work to asbestos-lined walls while working at Archway School in Shroud.

A coroner recorded her death as being the result of "industrial disease". Gina Lees death years earlier was ruled the same.

Barnett is now taking legal action against Gloucestershire County Council over her death, blaming asbestos in the school.

But how many more families across the country will lose loved-ones as a result of asbestos exposure in schools?

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) assert it is impossible to link the role of asbestos exposure in schools to developing mesothelioma as being the sole cause of death for a teacher, taking into account other accumulative factors, such as previous jobs. It adds that as a group teachers "do not stand out as a higher risk" to any other professionals working in other public buildings like hospitals. The HSE said asbestos causes around 5,000 deaths every year.

Thousands of schools were built between 1945 and early 1980s, using Asbestos Containing Materials (ACMS), such as crocidolite and amosite, with the latter estimated to be 100 times more likely to cause mesothelioma.

An HSE report, written in 2004 on the management of asbestos in schools, stated "a high proportion of our present schools contain asbestos and represent the potential to release deadly fibres".

The Medical Research Council in 1997 also confirmed: "It is not unreasonable to assume that the entire school population has been exposed to asbestos in school buildings."

Since 2000 all asbestos has been banned from the building trade but the HSE stresses that asbestos can be found in any building built before this time, including houses, factories, offices, and hospitals.

All of which confirms that old school buildings abound throughout Britain and that they potentially pose a threat to children and staff, something that is made worse by local authorities that fail to manage asbestos in these structures properly.

Lack of uniform approach

At present asbestos removal in schools is reliant on each local authority to follow up and manage after their schools have been inspected.

Jon Richards, who is joint chairman of Asbestos Testing and Consultancy, whose contractors help identify and remove asbestos in schools, said: "The way asbestos is managed in school is better but it is still not great in quite a few schools across the country. The situation has improved but it is on a school by school, local authority by local authority basis. It differs a lot.

"There's an obligation for them to have a survey, an assessment of where the asbestos is. Whether they use that information is another thing altogether – some don't even have a survey on site. Others don't follow up."

He added: "I have heard about people getting an asbestos-related illness from pinning into walls but the problem is when someone contracts an illness of this type you're never going to be 100 per cent certain where the asbestos fibres that caused you the problem came from, was it case where you were in a building where asbestos was not kept in good condition? It's a balance of probabilities.

"Now if you can prove that you're in a building with asbestos in poor condition then that building or the people responsible for the building becomes liable. This changes what was done previously when you had to prove unequivocally where you were exposed and the exposure, and that the building at that time caused you the illness."

An HSE spokesman said it works with schools to make sure they properly manage asbestos and the exposure does not pose a risk to staff in schools.

But he added: "It is impossible to make any inference about the role that asbestos exposure during the course of working as a teacher may have played by considering figures for the number of deaths with teacher recorded on the death certificate in isolation. This is supported by evidence from an independent epidemiological study of mesothelioma in Britain."

Lees however believes if a death certificate records a teacher has died of mesothelioma, "chances are strong" that the victims spent most of their professional lives teaching.

"The coroner looks at all the evidence and they come to the conclusion like they did in the case of Mrs Barnett and my wife that it was death by industrial disease. They have then concluded the person was exposed to asbestos as a teacher at school and that's what killed them," said Lees.

The Department of Education is set to publish new guidance on managing asbestos in schools. In February 2015 it earmarked more than £6bn (€8.3bn) for improving the condition of schools with the aim of dealing with asbestos affected buildings.

Whether that's enough is difficult to ascertain but there's no doubt it's too late for Gina Lees and Jennifer Barnett.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.