Beach Body Ready protest: Why aren't we more worried about naked men on the Tube?

Has our culture passed peak muscle mass? Earlier in April, fashion retailer Abercrombie and Fitch announced it was ending its longstanding policy of employing topless "beefcake" greeters in its major US stores, along with an immediate end to overtly sexualised advertising. It will also stop referring to its retail staff as "models" and will end its controversial policy of recruiting staff on the basis of their attractiveness.

Retail business analysts are in little doubt about the reasons for A&F's decision. The company's shares collapsed in value in 2014 by 39% and Michael Jeffries - the CEO who had personally steered the policy - stepped down in November of that year.

The A&F beefcake policy had always left the company toeing a narrow line between being seen as the most cool and desirable kid in senior high and coming across like the sneering, preening school bully

A reinvention of the brand has looked imminent ever since. The policies, which had sparked a string of court cases and PR scandals, always left the company toeing a narrow line between being seen as the most cool and desirable kid in school and coming across like the sneering, preening school bully.

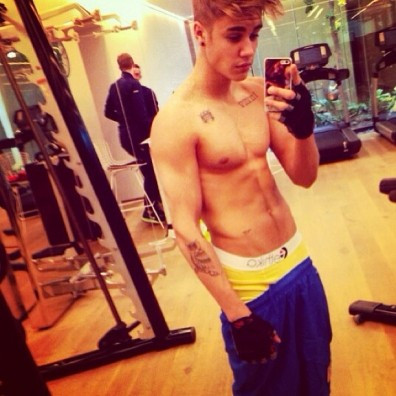

How much A&F's sexualised marketing gimmickry had to do with its decline in fortunes is a moot point. The announcement comes at a time when the rest of our culture seems ever more enthusiastic in attempts to install the sculpted, glistening male physique as a premium object of desire, aesthetic ideal or totem of personal attainment.

In March, a flurry of articles and blogs raised the bar on hyperbole. Men are now the more objectified sex, declared former lads' mag editor Martin Daubney. Writer and influential cultural theorist Mark Simpson went further: men are the new glamour models, he proclaimed.

Most such analysis contrast the increasingly ubiquitous male (near-) nude with the contemporary hostility to similar portrayals of women. Are we seeing some kind of like-for-like replacement? Are women's breasts, bums and legs being slowly covered up with the fabric ripped from the bulging frames of men?

There can be little doubt that we react very differently to portrayals of male and female flesh. A vivid illustration of this phenomenon has played out over recent weeks on the walls of the London Underground.

Protein World has been under fire from feminists for a billboard advert displaying the improbably thin model Renee Somerfield beside the slogan "Are you beach ready?"

The company appears to have been actively and deliberately stoking that fire, arguing with and insulting critics on social media. A petition against the advert has 65,000 signatories at time of writing and police have been called over alleged violent threats and malicious communications.

There was no such outcry about a similar ad for a similar product that graced the precise same hoardings a month or two earlier. The protein shake Bulk Powders was advertised with an entirely naked Adonis with chiselled muscles and pixellated penis, stepping off a Tube train as male and female passengers gaze upon him surreptitiously, captioned with the words "Reveal yourself".

Is it harmful?

To understand the very different reactions to the two adverts, one first has to appreciate the historical and political context in which the images appear. Without delving into the nuances of theory, many feminists would point out that women have spent centuries being valued and judged on little if anything more than their appearance and perceived sexiness and, understandably enough, they are sick to the back teeth of it. For men this treatment is a relative novelty and, as both Daubney and Simpson observe, by and large we are quite enjoying it.

The bigger question, I would argue, is not whether men enjoy being sexualised and objectified but whether they are harmed by it.

The academic literature is sparse and inconclusive but there is evidence that ever-greater numbers of young men and boys are struggling with self-esteem issues and eating disorders, while anecdotal evidence suggests use of dangerous anabolic steroids and/or fat-stripping stimulants might be on the rise.

There is an obvious temptation to place the blame for such problems firmly at the door of magazine editors, film directors and advertising executives who have conspired to make the six-pack and the V-shaped torso every young man's must-have accessory. Such an equation is simple and straightforward - and it is also profoundly wrong.

It is no coincidence male body-sculpting culture emerged in the rubble of the post-industrial economy and took hold among the first generations of working-class men to grow up in the aftermath of Thatcherism and Reagonomics. For centuries, young men had quietly asserted and performed their masculinity via their work, through providing for families at a young age, military service or even a carefully carved position within cultures of casual violence.

But the muscles that once wrought steel and hauled coal in Sheffield and Newcastle now pump iron and pull reps. The willpower and courage that once crafted mighty ships on the Clyde or in Philadelphia or churned out cars in Dagenham and Flint, Michigan is now instead turned inwards, nothing left to build but bulk.

The quest for bodily perfection can be seen quite profoundly in the journey from The Full Monty to Magic Mike - self-objectification travelling from desperation to a kind of proud, if sad, fulfilment.

Forty years earlier, another generation - my generation - of young men reacted to a similar sense of alienation and disengagement with a safety pin piercing, a mohawk and a cheap electric guitar.

The record labels, the management teams and the fashion houses quickly grasped punk, exploited it and sold it back to its creators, in the words of Joe Strummer, turning rebellion into money. The distance from nihilism to narcissism is a very, very short hop.

The same process has now overtaken body-sculpting culture and, as is the way with consumer culture, is simultaneously feeding it. The associated harms to young men's physical and mental health will not be addressed or contained by protesting a protein shake advert, picketing the Magic Mike sequel or demanding that Cristiano Ronaldo puts his shorts back on. Those are mere symptoms.

Boys do not need to be shielded from aspirational or sexualised images, they need to be secure that they have a meaningful role in society beyond zero-hours contracts, the call-centre and brief respite in the gym. They need to feel like they have more to offer the world than a perfect set of abs. Achieving all that will take more than removing a poster from the Underground.

Ally Fogg is a freelance writer and journalist based in Manchester, UK, who comments and blogs widely on issues of social justice, politics and male gender issues. He has previously worked in community media as a project manager and as lead author of the Community Radio Toolkit, as an editor and staff writer for the Big Issue in the North, and as an academic researcher in clinical psychology and epidemiology.

He can usually be found arguing with people on his blog at http://freethoughtblogs.com/hetpat/ or on Twitter @AllyFogg.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.