Brain damage caused by chronic stress reduced with experimental drug

Too much stress can lead to changes in the structure of the brain. However, this damage could be prevented by a new experimental drug, acetyl-l-carnitine, a study on mice has shown.

Published in Molecular Psychiatry, follows up on previous findings that hinted that the amygdala – the part of the brain that regulates emotions such as fear and anxiety – is affected by chronic stress. The scientists confirmed this, observing marked changes for mice in this region of their brain.

Over-stressed mice

The amygdala is a structure found deep in the brain. It is part of the limbic system that controls emotions and memories.

Stress is already known to have an affect on the limbic system, and now scientists have found evidence of damage to the amygdala in mice exposed to stressful environments.

The rodents were confined in a small space for 21 days. When the confinement period ended, they appeared to display antisocial behaviours as well as depressive tendencies.

Structural changes

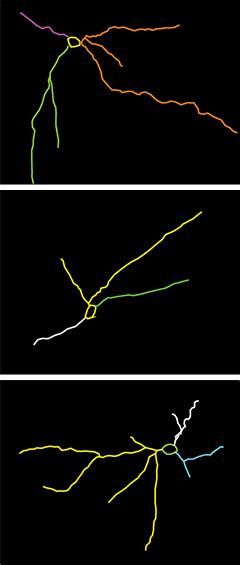

The scientists verified what had happened in their brains and discovered structural changes in two of the three regions of the amygdala.

While looking at the basolateral amygdala, the researchers noted that neuron branches became longer and more complex – a healthy sign of flexibility and adaptation. However, they also saw worrying changes in the structure of the medial amygdala. Here, neuronal branches forming crucial connections to other parts of the brain had appeared to shrink.

"When we took a closer look at three regions within it, we found that neurons within one, the medial amygdala, retract as a result of chronic stress", says lead author Carla Nasca.

This shrinking and the resulting loss of connexions increase the risk of developing anxiety and depression, according to the scientists. These findings suggest an explanation as to why stress in humans can lead to feelings of depression.

Drug to overturn the changes

The researchers have tested a solution to overturn the negative effects of this damage, treating some of the mice during their confinement with a molecule called acetyl-l-carnitine, an experimental drug that they believe works as a rapid-acting antidepressant.

The results were encouraging. These mice showed more sociable behaviours at the end of the 21 days in confinement, and their medial amygdalas appeared to have more branching than their non-medicated counterparts.

The team said that humans and rodents both produce acetyl carnitine naturally under normal conditions, and a number of depression-prone animals are deficient in it. They now plan to study whether people with depression have abnormally low levels of acetyl-l-carnitine.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.