Brexit is here, what changes?

Daily business between the United Kingdom and the EU will continue as before during an 11-month transition until the end of the year.

At midnight on Friday -- 1,317 days after British voters decided to leave the European Union -- Brexit finally came about. So what changed?

So far, not much. Daily business between the United Kingdom and the EU will continue as before during an 11-month transition until the end of the year.

This will allow London and Brussels to negotiate new arrangements to guide future relations, but in the meantime there are some practical changes.

The United Kingdom has left the EU and the union has lost one of its largest and richest states, the first ever to quit the project.

The EU has therefore lost 66 million inhabitants -- leaving it with a population of around 446 million -- along with 5.5 percent of its land mass.

If Britain ever does decide it wants back in, then this will be a matter for EU accession procedures as for any outside applicant.

In Brussels, the lowering of the Union Jack outside the European Parliament symbolised a concrete change: Britain is out of the union and a "third country".

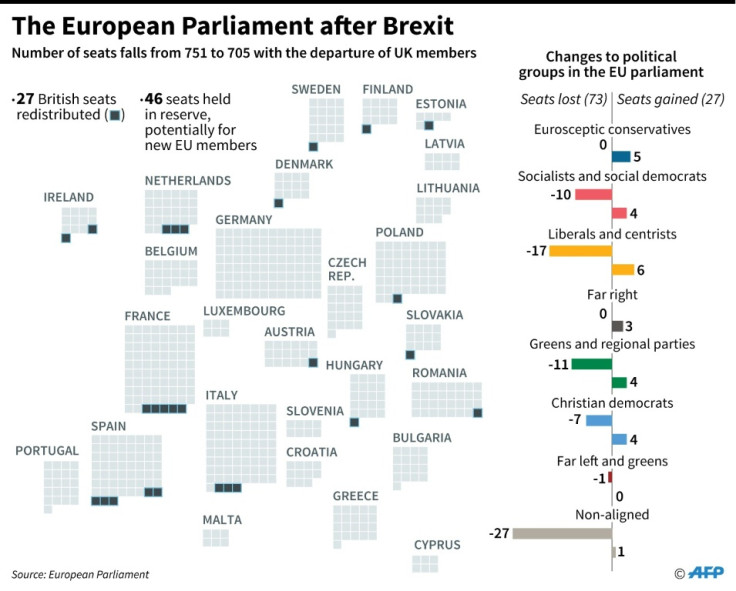

It has no MEPs, the 73 Brits elected in May have left. 46 of the seats will be kept for future EU members and 27 distributed among under-represented countries.

Britain no longer has to nominate a top official to the European Commission, although London failed to do so last year and its seat is already vacant.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson will no longer be invited to summits of the European Council of leaders, and ministers no longer attend EU council meetings.

As non-EU citizens, Brits are not eligible for senior bureaucratic posts in Brussels, but many have already secured dual nationality and residence rights.

More junior officials whose careers began before Brexit will stay in post.

Britain will, however, continue to pay into the EU budget as the second largest net contributor after Germany until the end of the transition.

According to the United Nations, around 1.2 million British citizens live in other EU countries, mainly in Spain, Ireland, France, Germany and Italy.

And according to the UK stats office, another 2.9 million citizens of other EU countries live in Britain, around 4.6 percent of the population.

Under the withdrawal agreement signed by both sides, both sets of expatriates retain the rights they had before Brexit to work and reside in their host country.

But Britons in Europe and EU citizens in the UK may have to register with the authorities and individual member states will set up procedures of their own.

Free movement will apply until the end of the transition. Afterwards, the withdrawal treaty says EU nationals will be able to stay in the UK if they continue to work.

The UK government has said it intends to end "freedom of movement" for future EU arrivals, and precise details of reciprocal rights will be negotiated after Brexit.

Britain has, of course, already spent years negotiating with European Commission official Michel Barnier's Brexit task force on the terms of its departure.

But these negotiations changed after Friday, when the "Article 50" procedure in the European Treaty expires and the UK becomes a third country.

The UK nevertheless remains subject to EU law and the European Court of Justice until the end of the transition, and in any judgements in cases pending from before the final departure.

Barnier is in talks with EU member states to draw up a negotiating mandate for a trade agreement to govern cross-Channel commercial ties after the transition.

This will then be hammered out with UK officials in the same way as Europe's free trade agreements with other third countries, such as Canada or Singapore.

Barnier will unveil the goals of his draft negotiating parameters on Monday, but EU leaders have already warned that Britain will not enjoy the benefits of membership outside the bloc.

Copyright AFP. All rights reserved.

This article is copyrighted by International Business Times, the business news leader