Is brilliance a male trait? Some women tend to think so

A study suggests that women are less likely to apply for a job if it demands intellectual genius.

Despite efforts to make the workplace more gender balanced; most top positions continue to be filled by men. One new study suggests that this may be partially due to women's perceptions of the role.

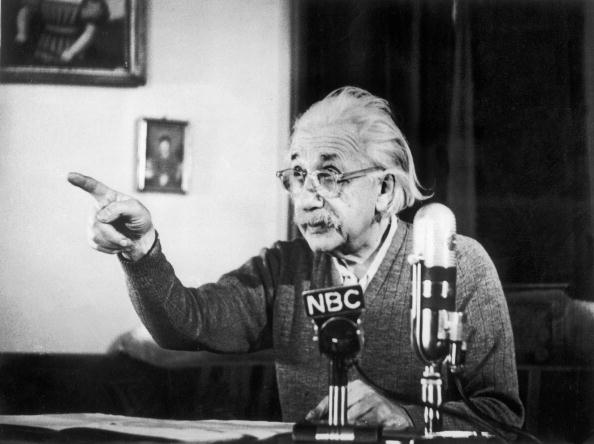

Research published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology claims that female candidates are deterred from applying for jobs that call for brilliance and intellectual genius because they consider these to be specifically male traits. Thanks to cultural stereotypes, we are more prone to associate Albert Einstein with being brainier than Marie Curie or say, Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize in 1983 for the discovery of genetic transposition.

"We know that women are underrepresented in fields whose members believe you have to be brilliant to succeed," Andrei Cimpian, an associate professor in New York University's Department of Psychology and the study's senior author explained. "These findings reveal one reason why this is the case: when certain fields or jobs are linked to intellectual talent or brilliance, which is seen as a masculine trait in our culture, women's interest declines."

As part of their study, researchers conducted a series of experiments on multiple groups of male and female subjects. In one part of the study, 199 male and female undergraduates were asked to list their interests in various internships and fields of study, from science, technology, engineering and maths to social sciences, business and humanities.

These opportunities were described differently to the subjects, with some requiring "brilliant" or "intelligent" applicants while others needed "motivated" and "passionate" people.

The results indicated that among the subjects, women believed they could not be as "brilliant" as their male counterparts and tended to shy away from activities that would require high levels of intelligence and preferred to opt for internships with other descriptions.

On the other hand, the male subjects were not particularly affected by the need for brilliance and were less reluctant to apply for those positions.

In another experiment, school-going girls and boys were asked similar questions.

"In earlier work, we found that girls start to associate 'smartness' with boys by the time they are six years old," co-author Sarah-Jane Leslie, the Class of 1943 Professor of Philosophy and director of the Program in Linguistics and the Program in Cognitive Science at Princeton University, said.

"These new findings show that the effects of these stereotypes persist over time, continuing to shape women's educational and career trajectories well into adulthood."

Thirty eight other adults of both genders were asked to make choices regarding job opportunities, and in follow-up research around 600 subjects were asked about how they felt about positions that demanded "brilliant" applicants.

First author Lin Bian, a visiting researcher at NYU believes these stereotypes also undermine women's sense of how they might fit in with others — their sense of belonging in the field.

Considering that jobs that require "brilliance" and "genius" may restrict many qualified people from applying, Cimpian agrees that there is a higher tendency for women to infer that they will encounter a less-than-welcoming environment in these fields – "that they won't fit in and be accepted and successful".

"De-emphasizing the role of brilliance in achieving success may be one way to reduce the impact of the cultural prototype of the 'brilliant person' on women's interest and involvement," he recommended. "Our findings showed that when the same opportunities — majors, internships, and jobs — were described as requiring dedication and effort instead of brilliance, women's interest remained high."