Britain is still searching for Maddie – why don't we care about missing children of colour?

There is little to no coverage of non-white missing children, and lack of communal empathy.

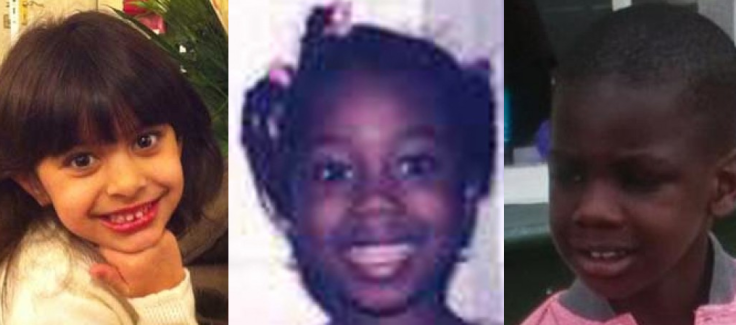

Elizabeth Ogungbayibi has been missing since 2006. She was 5 years old when she disappeared from Manchester. Aamina Khan went missing from Croydon in 2011 at age 6. Sean Iregi, then 7, went missing while on holiday with his family in Kenya in August 2016. Heydari Nastaran, then 7, has been missing for a year.

Moses John was 13 when he went missing from the East Midlands in 2015. Shahil Tariq, 15 years old, has been missing from West Midlands since March. Precious Myles, also 15, has been missing from London since March.

Hieu Thi Le, Suleimane Djalo, Helen Kebede, Anh Hoang, and Henry Oladimeji – children who are also missing from their homes.

You are unlikely to have heard of them. Unlikely to have seen a photograph of their faces, to have read details of their stature, hobbies, or interests, certainly not in any great detail.

Doubtful you will have witnessed a pained plea from their parents asking for their safe return, not on TV, nor in articles in mainstream media dedicated to their story.

Alongside this — played out like a horrific ten-season drama — the tragic disappearance of a child, presumably taken from her bed while on a family holiday in Praia da Luz. It is the ten year anniversary of the disappearance of Madeleine McCann, a household name for the saddest of reasons.

In what has at times seemed a perverse national obsession, you may find interview after interview, an official website, imagined impressions of what the child may look like at an older age, forums that have not merely shared thoughts, but asserted with unknowing certainty the fate of the child.

Kate and Gerry McCann have been scrutinised, bouncing between blame and innocence. Then, of course, there is the former Portuguese detective Goncalo Amaral, who appears between court cases with the McCanns to make one seemingly outlandish claim after another — most recently that Madeleine's body was cremated in the coffin of a British woman.

There is simply nothing useful about the extent in which both media and public have consumed the disappearance of a child like they have with Madeleine. It says, perhaps, a lot more about us as a society, that there are certain ingredients that captivate us in a particular way, and what those components need to be to keep us gripped like this.

The abuse and death of Peter Connelly, better known as Baby P, also took the nation towards a similar sense of concerned fixation. In what often seemed like the same unmanageable chaos that results in bricks thrown through paediatrician windows, misunderstood to be paedophiles — this all consuming outrage at Peter's death would eventually spiral into violent threats against the woman then in charge of Haringey Social Services.

I worked closely on the story. At the time, I worked in the press office of the North London hospital that had flagged the boy's abuse to social services. We followed it carefully, unravelling slowly in local newspapers as details of the torture and trauma were written in short paragraphs, buried between pages. The case eventually, understandably, erupted into mainstream media. Two thirds of a front-page — a photograph of the boy looking up into the camera. The care and attention this story suddenly garnered had shifted with this image beside it. The images of Peter, much like Madeleine, as cherubic as they were, never left either story's side.

Crimes against children understandably generate public emotion and engagement, as we respond to our disbelief that moral corruption has been acted out against the most vulnerable. But there is more at play as to what we have come to be told is worthy of our interest and outrage, and who it is that we are able to see as vulnerable.

We witnessed much the same compulsion with the death of JonBenet Ramsey — another fair haired, light-eyed child who represented what we are taught to associate with the image of virtue. As such, our concern becomes overwhelming — how can it not, when we are told there is one look to represent the absolute face of unequivocal innocence?

It is a simple fact that the press are four times more likely to report on missing white children, than children of colour. Just as we have ingrained in us this representation of purity and what it looks like, we have come to believe that a lack of innocence has its own face. Just as white individuals are presented staggeringly as victims (or saviours) in news stories, films, and television shows, it is people of colour who are over-represented as criminals. It is harder then to flip the narrative, to elicit the same kind of engagement from their disappearances or deaths.

The press are four times more likely to report on missing white children than children of colour

When we have been taught to view blackness and browness as threatening, it is no surprise then that it is harder to identify such individuals as lacking safety and, ultimately, innocent. As such, there is an immense absence in highlighting missing or victimised children of colour in our press. There is little to no coverage, and lack of communal empathy.

There are currently thousands of vulnerable children in Britain paying the price for a system out of their control. Paying the price for a media which perhaps wrongly doesn't trust that we are capable of crying for, and investing in all children in the same way as we have understandably afforded the tragedy of the McCann's.

Chimene Suleyman is a writer from London based in New York. She writes a column on racial politics for Media Diversified, and recently released her debut poetry collection Outside Looking On. Follow her on Twitter @chimenesuleyman

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.