Can the art of cinema co-exist with the demanding industry of today?

Do artistic expression and pursuit of profit in the film industry directly cancel each other out, or can they co-exist?

How have big franchises like Marvel become the face of contemporary cinema?

When looking at the recent trend of sequels/ remakes taking up the majority of recent cinematic releases, there is no better example than the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

This iconic franchise originally began in 2008 with the release of 'Iron man' directed by Jon Favreuo, the film was an instant hit, grossing approximately £102,506,921 domestically opening week. Somewhat surprisingly so, due to 'iron man' being a relatively lesser known superhero at the time, and marvel itself being a smaller franchise than its competitor 'DC Comics'. Following on from this initial success Marvel studios put in place plans for several sequels in the form of 'phases', as of today the MCU is currently in its fourth phase.

Another tactic the studio employed was to sign actors to contracts that would last several years. This initially made actor Chris Evans sceptical about joining the franchise as Captain America, but was eventually convinced by Iron Man actor Robert Downey Jr.

It was clear that even in the early days of the studio they had every intention of becoming the multi-billion dollar iconic franchise they are today. But how was the studio able to be so consistent in creating so many successful movies, which ultimately culminated in the highest grossing film of all time in the form of Avengers Endgame which was released in 2019 reaching £1 billion worldwide opening week? One reason for this is suggested by the MCU's 'Falcon', Anthony Mackie. In 2017 at a comic con panel in London, Mackie stated "there are no movie stars anymore. Anthony Mackie isn't a movie star, the falcon is a movie star".

What Mackie was referring to, is that the main selling point of these films are the established characters. Not the plot, acting or direction of the film. This means that even before these sequels/ remakes are released they already have a guaranteed audience, meaning the studios don't need to rely on reviews/ advertisements as heavily as standalone movies do.

Another tactic used by big film studios like Marvel to gain profits from repeated sequels, is to create story arcs that pan across multiple different films. Avengers Infinity War (2018) was one of the first films in the franchise to do this, by combining characters from all the previous instalments to create a 'crossover film'.

By the time of the film's release the MCU had not only become hugely successful but it had also become a cultural phenomenon, this led to a sense of people not wanting to miss out. Prior to the release of the film there was an increase in people watching previous instalments after their cinematic release to make sure they were all caught up.

It is because of these tactics and an overall lack of risk taken when developing these sequels/ remakes that has led to their financial success, and led to them taking the forefront of the contemporary face of cinema. But this is also the same reason these films have faced criticism. In a 2019 interview with Empire, critically acclaimed auteur director Martin Scorcese compared these films to "amusement parks"and said "I don't think they're cinema". This analogy was likely referring to how these films offer quick easy entertainment without making a dedication to creating a piece of art.

While Scorcese makes a convincing argument, it is unfair to ignore some of the positive influences they have had on cinema. One of the main factors contributing to 'the death of cinema', is the significant decrease in people going to the cinema. This is mainly due to a significant rise in ticket prices(in the UK cinema prices rose from an average of £4.40 in 2000 to £7.25 in 2021), and the introduction of streaming services.

One of the most culturally significant moments in cinematic history was the release of Avengers Endgame because it made people excited to go to the cinema. There are countless videos online of people's reaction to certain points in the film, it returned a communal feel to the cinema experience which is what made cinema so special and unique. While the criticisms against these films are valid and they have made it harder for independent films to break through, it can't be said that they haven't contributed anything good for cinema.

Why is it so hard for independent filmmakers to break through?

One of the reasons independent films are finding it harder to break through is because they need funding. A lot of big budget studios will only finance a film, if they are guaranteed to make a return profit. This puts a strict limit on the artistic freedom independent filmmakers have when pitching their ideas/ scripts.

Quentin Tarantino's second directorial release 'Pulp fiction' was rejected by TriStar, despite the success of his first release 'reservoir dogs'. This is likely because of the scenes of graphic violence and depiction of drug use (which would restrict the age range of the potential audience). When the film was eventually approved it went on to win the 'Palme d'Or' at the 1994 Cannes film festival, securing Tarantino's auteurist reputation whose name is now a selling point of any film he is attached to.

The reason this is significant is because if this script was being pitched today the writers may have to remove some of the more risky elements, which is what made the film so iconic. Meaning from the perspective of an independent filmmaker it would appear the only choice you have is to craft a very safe down the middle story, or you won't receive funding at all.

Another way independent filmmakers may create a film is through self funding. This route allows filmmakers to avoid input from studio executives and allows them more creative freedom. Although, it also brings its own set of challenges.

Unless these independent filmmakers are sitting on a small fortune, they are going to be faced with serious limitations on what they can realistically achieve. They won't be able to rent out shooting locations, invest in special effects, buy music rights as easily as a major studio would be able to. They also might not be able to afford a good acting cast, which could result in their story not being brought to life in the way they had imagined.

This isn't to say that it's impossible to create a highly artistic low budget film, there are many examples of this happening. For example 'the blair witch project' was shot to look like it was from the perspective of film students with little to no budget, therefore the film was very cheap to make, costing only £500,000 (worldwide box office is 413.8 times production budget) It was because of this unique aspect that gave the film an exciting selling point, gathering an audience.

However, very few 'indie' films are this lucky, and even if the filmmakers can find a way to create a fully realised film on a low budget, they likely won't have the money they need to spend on advertisement. Meaning upon the film's release they will likely not return a profit and likely even face a loss.

Blade Runner: Industry and Art working together

Is this to say that big budget films and sequels can't be artistically expressive, not at all. However, the examples of films that do manage to do this, only manage to do so due to a few crucial factors. One of which being the director's name. Even today when we are seeing a decline in 'star directors', there are still a handful of directors who can attract an audience to any film they put their name to. One of these directors is Ridley Scott.

Scott originally directed TV advertisements then went on to start directing films in the late 1970s. He gained a reputation for his use of striking visual shots, innovative production design and leading female protagonists (as early as the 1979 release of 'Alien'), and went on to release several critically acclaimed and commercially successful films, such as 'Gladiator' and 'The Martian'.

But one film that really stood out was 'Blade runner'. Originally released in 1982 to polarising reviews and a poor box office reception in North America, grossing around £7.5 million opening week.

Some of the reviews for this film critiqued the film for its slow pace and lack of action, which Warner Bros also feared might happen, therefore before the film's release they insisted Scott do something to make the film have a more mainstream appeal. Scott reluctantly obliged and added a voice over by Harrison Ford (who played the protagonist Rick Deckard) explaining the plot points to help the audience follow the narrative. He also removed some scenes to cut down on the runtime, including a plot defining dream sequence.

Despite these changes insisted by the studio, the film still did not do as well as they hoped at the box office, and Scott himself was reportedly very upset with the direction he was forced to take.

Looking at this example it would appear that this conforms to the argument that big studios harm the creative potential of artistic films to make a profit. Some years after the original release of Blade Runner in 1982, Scott was still unhappy about the theatrical release version of the film and off the back of the success of Thelma and Louise (1991), in 1992 Ridley Scott decided to create the director's cut of Blade Runner to bring to life the film he had initially envisioned.

Surprisingly Warner Bros approved this edit and even screened the cut at the Cineplex Odeon Fairfax Theater in Los Angeles. The director's cut then went on to be released worldwide and has become a cult classic regarded as one of the best science fiction films of all time. This would imply that there can be big budget films released with the intended vision of the filmmaker despite being backed by a major studio like Warner Bros.

However, it's likely that Ridley Scott's director cut of Blade Runner was only approved because of his star status as a director and possibly due to the unauthorised 1990 and 1991 theatrical release of the workprint version of the movie, with Warner Bros wanting to take back ownership of the film.

In a 2016 directors roundtable interview with the Hollywood Reporter, Ridley Scott brought up the topic of sequels to the table (that included Quentin Tarantino, Danny Boyle, and more). He asked the question "do you think sequels are wearing us out a little bit… I think they do", he then went on to say "you can't blame the studio for wanting to do it because it's a financial return".

At the time of this interview it had been announced that Scott was working on the long anticipated Blade Runner sequel. This quote from him would imply he was sceptical about reimagining a classic film.

Upon the release of said sequel (Blade Runner 2049 (2017)), it received praise for its jaw dropping visuals and deep thought provoking philosophy running through the film which is what made fans fall in love with the original, but it also expanded upon the original film while expanding by exploring the theme of material consumption and an obsession with the virtual world, which has become more relevant in today's society.

This is a perfect example of industry and art working harmoniously, because the studio knew the film would attract a guaranteed audience so they could allow Scott to pursue his creative vision.

How does the rise of streaming services influence this debate?

A noticeable development to the landscape of cinema that also plays a role in this debate is the emergence of streaming services. Since the release of Netflix's streaming service in 2007 it has consistently been leading the competition with recent competitors including Amazon Prime video, Disney+, Hulu, Apple TV+ and countless others all competing to win the so called 'streaming wars'. The impact these services have had on the type of film content being produced has been both very positive and negative.

First, let's look at the negative impact. Initially streaming services were hosting platforms, where people would watch pre-existing content from external producers. Since then streaming services have gone on to produce their own content that can be viewed exclusively on their streaming service for a monthly/ yearly fee. This is an example of vertical integration, where a company owns all aspects of a product (in the case of film that would be pre-production, production and distribution).

This is a widely condemned practice because it forces out smaller businesses that would supply bigger companies with an element of production and discourage other businesses from entering the marketplace. In some instances vertical integration can lead to legal consequences.

One streaming service known for its use of vertically integrated content is Disney+, while Disney+ does host content from external sources, their main draw for new subscribers is their exclusive content. Disney+ owns the rights to many beloved franchises including Star Wars and Marvel.

The only way to view new content for these franchises is through Disney+ (with the exception of some cinematic releases). By prioritising exclusive content streaming services following this module do not provide a viable alternative for independent filmmakers looking for an alternative to theatrical releases, because they are not allowing room for external contributors to their platform.

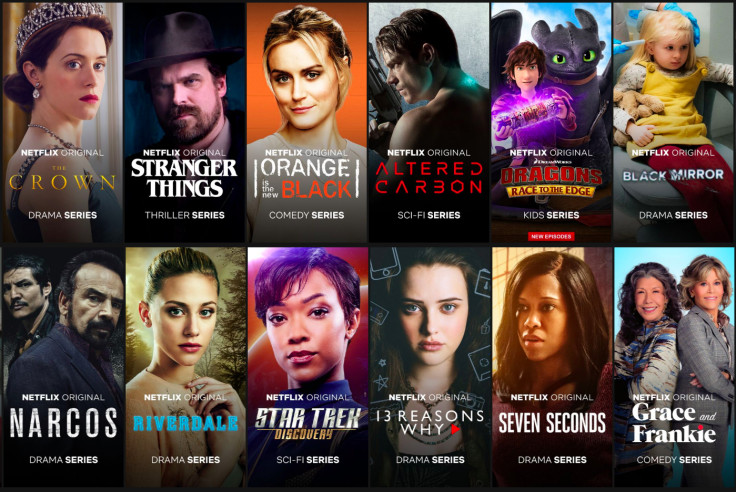

Although not all streaming platforms follow this model. Netflix also now hosts original content called 'Netflix originals'. However, unlike other streaming platforms Netflix allows external contributions and even funds a lot of independent filmmakers to produce film/ TV which would then go on to become a netflix original.

It's become a sort of running joke in recent years about how many Netflix originals are funded and how easily Netflix gives funding to independent creators.

The adult cartoon, South Park, even referenced this by depicting a Netflix executive answering the phone with the greeting "Netflix, you're greenlit. Who am I speaking with?" Jokes aside, this business model does offer a viable alternative to theatrical releases for independent and alternative filmmakers. Also because of the variety and scope of Netflix's content there is a lot of room for filmmakers to experiment with the kind of content they produce.

What does this mean for the future of film?

But what does this mean for the future? It's unfair to say that the films being produced today are bad, there is still a consistent level of quality being released every year. But these are films often funded due to director notoriety, so what happens when said filmmakers and directors stop producing films.

Without allowing new directors with unique voices to break through in today's landscape of cinema, who will be making the films of tomorrow? Will cinema become a factory line process only releasing 'safe' 'down the middle' content? Or will streaming services allow new directors to break through creating a new generation of filmmakers that will produce new exciting content for generations to come? It's hard to say, but one thing for certain is that the film industry is in a delicate position.

All this taken into consideration I believe that there is an attainable future where industry and art can co-exist. After All there is a somewhat circular nature to cinema, in the 1990's there was a rise in commercially successful arthouse films like 'Shawshank Redemption', 'Good Will Hunting', 'Pulp Fiction' and 'Fight Club'. These films gained popularity because people had become tired of the traditional Hollywood formula of 80s blockbuster action films. So perhaps we are about to witness a similar reprisal in the near future.

But in order for this to happen there needs to be more investment in independent filmmakers and there needs to be a more accessible way for new filmmakers to get their films seen by audiences for this future to happen. And as audience members we need to be more willing to explore different kinds of cinema to provide an audience for new filmmakers trying to break through.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.