Can depression be treated by making brain signals travel the wrong way?

A recent study led by Stanford Medicine has revealed that magnetically stimulating the flow of abnormal brain signals can be used to treat severe depression.

In a recent study, Stanford Medicine scientists have discovered a potential treatment for depression by reversing the direction of abnormal brain signals. Using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a "non-invasive" procedure that involves using magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain, has been shown to effectively improve symptoms of major depression.

Before research had commenced, Dr Anish Mitra, MD, PhD and post-doctorate fellow in psychiatry and behavioural sciences at Stanford University said: "The leading hypothesis has been that TMS could change the flow of neural activity in the brain. But to be honest, I was pretty sceptical. I wanted to test it."

In order to test this hypothesis, Dr Mitra teamed up with American neurologist, Marcus Raichle, MD, who is also a professor of radiology at the Washington University School of Medicine in Saint Louis, Missouri.

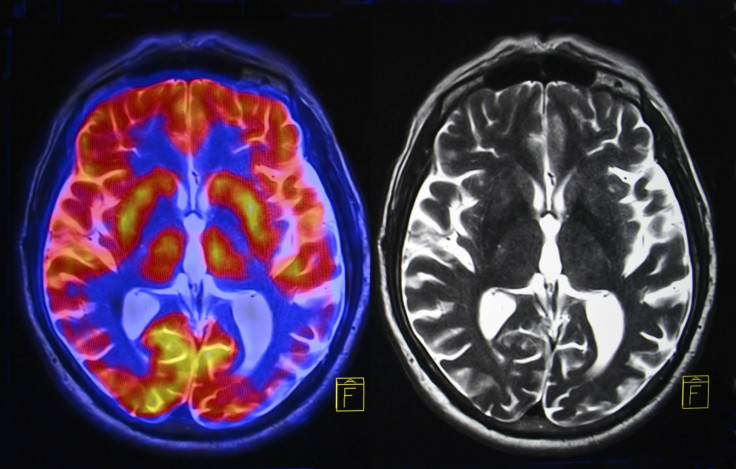

Within his own laboratory, Raichle developed a mathematical tool that analyses functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which is commonly used in locating active parts of the brain. The basis of the analysis was using small differences in timing between activation of various parts of the brain, which also revealed the direction of the specific activity.

Mitra and Raichle later teamed up with Stanford associate professor of psychiatry and behavioural sciences, Nolan Williams, MD, whose team has treated depression in their patients by advancing the use of magnetic stimulation and tailoring it to each patient's anatomy. This treatment, known as Stanford Neuromodulation Therapy (SNT), incorporates imaging technologies in order to stimulate brain activity and reduce depression with high-dose patterns of magnetic pulses.

To strengthen the hypothesis further, researchers enlisted the help of 33 patients, all of which had been diagnosed with major depressive disorders that proved highly resistant to treatment. To ascertain comparisons in the accumulated data, twenty-three patients received the SNT treatment, whilst the remaining ten received a "placebo" treatment that closely mimicked SNT, but avoided any magnetic stimulation.

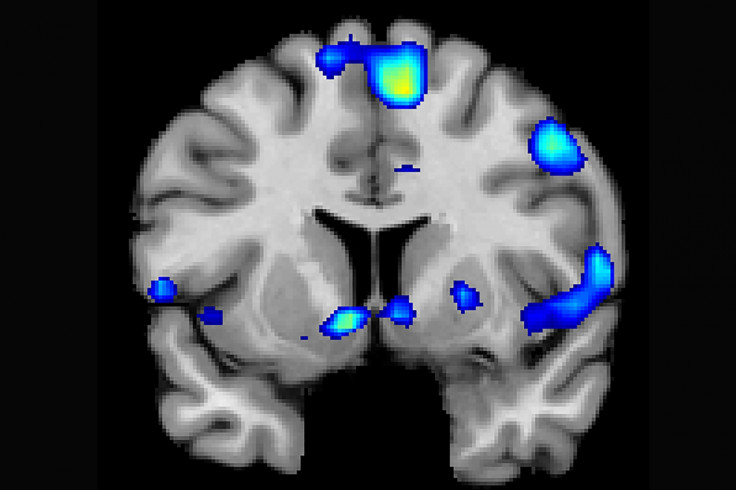

When the scientists analysed fMRI data of the brain, something significant stood out. In a normal brain, the anterior insula, a region which integrates bodily sensations, sends signals to another region that controls emotion, known as the anterior cingulate cortex. In the brains of approximately 75 per cent of the subjects, the typical flow of activity was reversed – specifically, the anterior cortex sent signals to the anterior insula.

Dr Mitra commented on this discovery in the published study, saying: "What we saw is that who's the sender and who's the receiver in the relationship seems to really matter in terms of whether someone is depressed."

Mitra continued: "It's almost as if you'd already decided how you were going to feel, and then everything you were sensing was filtered through that. The mood has become primary."

However, when depressed participants received the SNT treatment, in just one week, the natural flow of neural activity shifted back into the normal direction, which corresponded with the improvement of their depressive state. The scientists ultimately concluded that patients with the most severe depression and misdirected brain activity would benefit the most from this treatment.

Williams stated: "This is the first time in psychiatry where this particular change in a biology – the flow of signals between these two brain regions – predicts the change in clinical symptoms."

"When we get a person with severe depression, we can look for this biomarker to decide how likely they are to respond well to SNT treatment," Dr Mitra said.

Results of this fascinating study were published by the scientists on May 15th in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, with Dr Mitra serving as the lead author and Raichle and Williams serving as senior authors, respectively.

Commenting on the results, Raichle said: "Behavioural conditions like depression have been difficult to capture with imaging because, unlike an obvious brain lesion, they deal with the subtlety of relationships between various parts of the brain."

He concluded: "It's incredibly promising that the technology now is approaching the complexity of the problems we're trying to understand."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.