Can smartphones replace your GP? New medtech apps put specialist knowledge in patient's pockets

One evening in late 2013, Brice Beakley wasn't feeling very well. The 15-year-old from Doylestown, Pennsylvania, had been hit by a hard tackle at football practice earlier in the day and still hadn't recovered. Not knowing what else to do, he picked up his iPad and Googled his symptoms: upper abdominal pain and left shoulder pain. Doctors later credited the search engine with saving the teenager's life.

What Google's results told Beakley was that he had ruptured his spleen, a potentially fatal occurrence that requires immediate medical intervention. After being rushed to the hospital by his parents, doctors performed emergency surgery to remove the spleen. Beakley was saved.

While Beakley's case may be exceptional, it illustrates an ever-increasing reliance on consumer technology when it comes to healthcare. The problem with searching symptoms through Google, however, is that the benefits are often outweighed by the downsides. People are often presented with the worst case scenario and search results can undermine medical authority.

This is what a new generation of apps is aiming to fix. The apps combine a smartphone's sensors with the vast power of cloud computing in order to accurately diagnose a disease or illness - ranging from skin cancer to eye disease. In some cases, the app's creators claim that the technology performs better than the average GP, potentially paving the way for apps to skip primary healthcare altogether and refer patients directly to specialists for immediate treatment.

"I believe that GPs play a very vital role as the first point of contact for people when they become sick or worry about something," Dick Uyttewaal, the CEO of SkinVision, told IBTimes UK. "But there is an awful lot of work that they currently do where they don't add value and that could be replaced by technology.

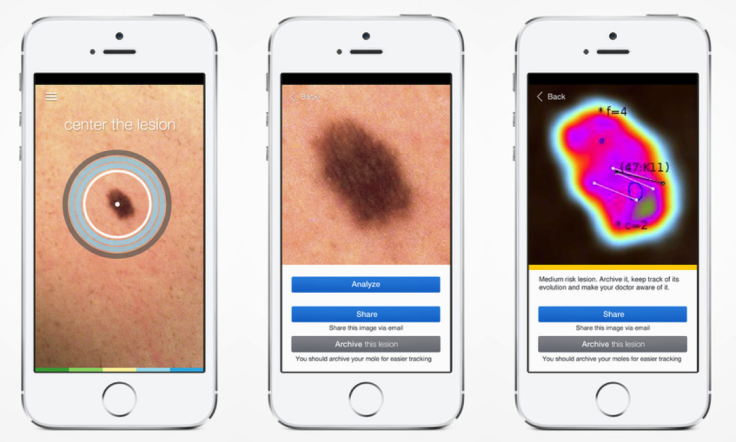

Uyttewaal's SkinVision app links a smartphone's camera to an algorithm capable of detecting melanoma. A study published in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology found that the app was 81% accurate in recognising skin cancer, bringing "the average eye of a dermatologist" to a smartphone. "That could mean that certain people with a certain risk profile could be directly sent to a dermatology consultant instead of first being seen by a GP," Uyttewaal said.

'Professional and patient caution'

The sudden emergence of this technology means that the regulation surrounding it is a long way behind where it needs to be. Before overburdened GPs can have their workload reduced through such apps, this issue will need to be addressed.

Professor Maureen Baker, the Chair of the Royal College of General Practioners, believes that while such apps can prove helpful in providing knowledge or advice, the current lack of safety standards in the UK mean they could never be put to use in any meaningful way.

"There are many functions that apps can bring into medicine and we should welcome and explore that but at the moment there's still probably a reasonable degree of professional caution and indeed public and patient caution," Baker told IBTimes UK. "People want to know: Is it safe? Can we trust it? Is it reliable? Kitemarking or assurance in general isnt' readily available, either to patients or to professionals. The medical regulatory framework that we now have for medical devices is not fit for purpose for 21st Century apps and the way in which technology is evolving. And that's a problem."

Following a study at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitat Clinic in Germany, SkinVision became the first skin cancer app to be CE marked for usage in the European Union, though this has little practical application when it comes to being able to refer people directly to a dermatologist. Instead, Utteywaal hopes that the SkinVision will be used as a complementary tool to existing medical detection methods, rather than a replacement.

"The issue with medical studies is that technology is fixed before the study starts and the study took one year with the publication going live in 2014," Uyttewaal said. "In contrast in the app development sector a lot of change happens in two and a half years and the world is completely different.

The rise of medtech apps

SkinVision - Analyses moles for signs of skin cancer

AliveCor - Detects serious heart conditions

Peek - Uses lens adapter to conduct professional eye exam

STD dongle and app - Uses dongle to detect HIV and syphilis

Mobilyze - Tracks behaviour patterns to identify mental health conditions

"We want the app to bring people into the healthcare system who otherwise might not be. There is a risk of false positives or false negatives — though none have been reported yet — so the online assessment is part of a wider journey for the customer."

'Computers can't make ethical decisions'

Another of the biggest limitations with current medtech apps is the inability to understand a patient's condition within a broader context. Rob High, chief technology officer of IBM Watson (of Jeopardy! fame), believes that despite advances in artificial intelligence, computers remain very limited in scope.

Speaking to IBTimes UK at the recent Hello Tomorrow conference in Paris, High said: "Computers can't make the ethical decisions that a doctor can on a broader scale, for example the knowledge that a patient has a sick daughter and therefore one course of treatment should not be chosen over another despite it being more beneficial as it would put them out of commission for a few days a week - leaving her unable to care for her daughter."

This idea of placing information in context is one shared by Baker, who also claims that a patient-doctor relationship can be therapeutic for the patient. According to Baker, trust plays an important role in assisting a person's recovery or handling of an illness.

"These days, people very rarely have just one thing wrong with them at any one time," Baker said. "Certainly machines, no matter how good they are, are nowhere near being able to handle that complexity at the moment, and nor are they likely to. I don't see machines replacing a significant proportion of doctors - not in the next five to ten years, and I think probably not for many years, if ever."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.