Child abuse in sport is not an issue of the past – the whole culture needs to be changed

Several victims have come forward, which raises a number of uncomfortable questions for sporting organisations.

The FA and the NSPCC opened a hotline this week to encourage survivors of sexual abuse to come forward. This was following the revelations from four footballers, who waived their anonymity as victims, that they were sexually abused as children by their coach Barry Bennell.

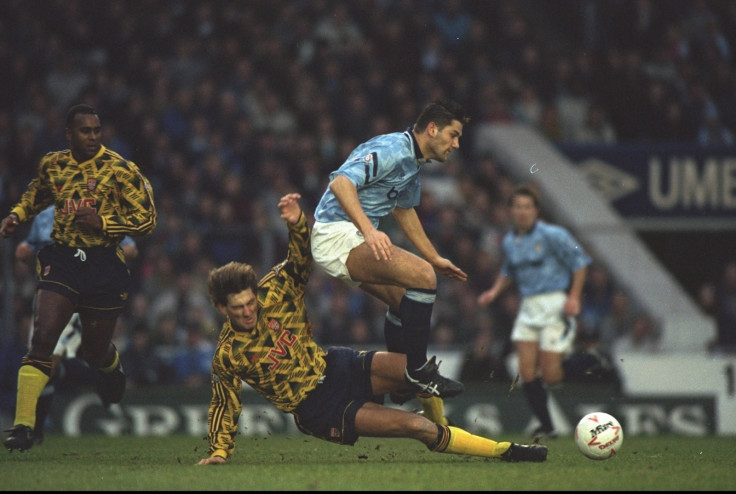

Former Manchester City footballer David White was the fourth footballer to disclose sexual abuse, following ex-Crewe players Andy Woodward and Steve Walters, and former Tottenham forward Paul Stewart.

Bennell was sentenced to nine years in 1998 after admitting 23 specimen charges of sexual offences against six boys aged nine to 15, and again in 2015 for a historic sexual offence committed against a 12-year-old boy.

Led by Andy Woodward, the former players started what is sure to be a wave of disclosures about sexual abuse in sport as more than 50 calls were made just within its first two hours of opening. The helpline, though welcome, does nothing to assuage the question as to whether the environment in which children play sport is safe.

This raises a number of uncomfortable questions for sporting organisations and adults who oversee the participation of children. Why is it that it is adults are speaking up but children are not coming forward in greater numbers to identify abuse or poor practice? And what is the role of elite sport in creating cultures where abuse thrives? The setting up of a helpline also seems to feed complacency that this is simply a retrospective issue and can't happen now.

The FA's statement on its website praises the bravery of the footballers and calls on others to come forward, it also quite properly talks about changes that have occurred over the last two decades. These include child protection systems, procedures and standards, a mandatory safeguarding and protecting children workshop undertaken yearly by 35,000 volunteers within football every year, the fact that every junior football club has a designated Welfare Officer and all adult volunteers undertake vetting and barring (DBS) procedures.

These are all welcome steps in making it more difficult for those who wish to use their involvement in sport to abuse their position of trust. However, these measures are directed at adults, focused on risk and reporting concerns after the incident has occurred in the majority of cases. There is also little awareness among the children – the people these policies are seeking to protect are unaware of their rights.

From 2003 to 2013 I was involved in developing Participation Through Sport (PTS) and undertook consultations on behalf of the FA in 2006 and 2012 seeking to listen to children's experiences and priorities in taking part. As a result a film "Listening to Children in Sport" was produced supported by the FA, Sports Leaders UK and the Cheshire Safeguarding Board. This established that children's view of child protection is more holistic than the procedural and legal context that focuses on ''significant harm'' (Children Act, section 47).

It means they don't like sarcasm from adults, being left out of teams and being shouted at or belittled. Their priorities are to have fun, team work and friendships: meaning that the quality of experience is always more important than the result. All qualities the FA found in its own consultation in 2011, as part of producing its National Game Strategy in 2011, entitled without a hint of irony "Your Kids, Your Say".

Achieving the above and empowering children to speak about their concerns means creating a positive environment that addresses children's priorities. It means involving them in decisions in relation to their participation; such as choosing the captain, rotating players, taking it in turn to take penalties, free kicks and corners, to name just a few. The film documented the fact that if children are involved in decisions they would be more likely to open up and share concerns.

It's an unfortunate truth that all studies taken within and outside sport suggest that the majority of children do not trust adults and report ill-treatment or abuse. The major study to date in relation to child protection in sport by Edinburgh University found this to be the case and identified that the participation of children is not present within sport.

That is why in sport, as in other areas where abuse has come to light such as the Catholic Church and at the BBC, people are adults by the time they feel able to speak out. Addressing this means changing the way children are viewed and experience sport.

Children experience sport under the direction of adults who shape their experience. This reflects the values of professional sport where winning is the priority. Plus, children play football for the entertainment of adults. As the former MBA basketball player John Amaechi expresses, in no other walk of life would the behaviour of coaches shouting at children be tolerated.

Professional football trades in young footballers, with kids as young as five in academy systems, which puts unrealistic pressures on children. A study of the football academy's trade in children, detailed in Every Boy's Dream by Chris Green, shows that less than 1% of the 10,000 boys in the system at any time become professionals. This is responsible for the toxic environment in which football takes place.

It is within this context we should understand the Daily Telegraph campaign against the abuse of referees earlier this year that describes parents routinely abusing young players, with 3,731 incidents of misconduct in children's football in a 15 month period.

Children and parents are often scared to speak out and share concerns, for fear they will be dropped from the team. They also collude by keeping silent because the coach has the power to make their child a star, as in the case of when Sheldon Kennedy, the Canadian ice hockey player, revealed systematic abuse from a coach through his childhood; only then did other parents and officials reveal their suspicions after remaining silent.

If we want to end child abuse in sport once and for all we need to recognise that children have the ability and motivation to shape their own enjoyment. Pressured, unsafe environments are avoidable.

The hotline will be available 24 hours a day on 0800 023 2642.

Jameel Hadi MBE is a Lecturer in Youth Justice, Care Leavers and Looked After Children at the University of Salford. Follow: @jameel_hadi

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.