Cholera-like diseases ride on El Niño to spread to new shores

El Niño could spread waterborne diseases, like cholera, across the ocean to new continents, scientists have warned. Research published in the journal Nature Microbiologyshows that Vibrio diseases, devastating illnesses caused by waterborne "vibrio bacteria", have been observed in Latin America whenever warm El Niño waters have reached the land.

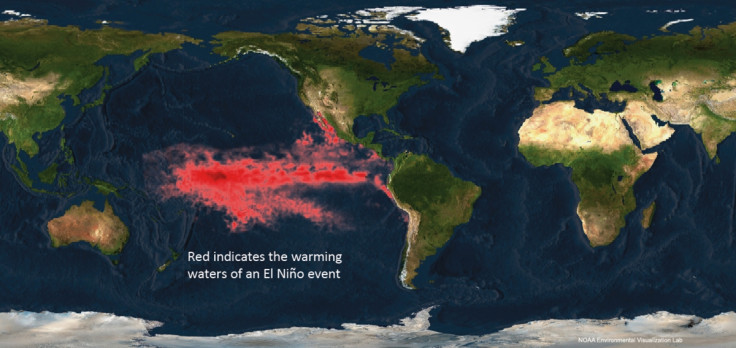

El Niño is a climatic event that leads to an oceanic warming of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean, including waters on the tropical west coast of South America. El Niño takes place every two to six years, but with different degrees of intensity.

While El Niño's effects on local weather and extreme meteorological events are well-documented, scientists still don't fully understand its impact on health, especially in the long term. This latest study brings clues to explaining how diseases spread with El Niño, and how new pathogens appear in regions where they had previously not been seen.

Cholera outbreak in Peru

The team of scientists from the University of Bath note that the beginning of some Vibrio disease outbreaks in Latin America was reported around the same time El Niño's effects started to be felt on the land, with warm water reaching the shores.

The scientists show that over the last 30 years, during the three last major El Niño events in 1990/91, 1997/98 and 2010, new waterborne diseases were reported. The most tragic episode was a cholera outbreak in Peru, caused by bacteria Vibrio cholerae, which killed more than 13,000 people in 1990-91. New variants of the Vibrio parahaemolyticus pathogens also emerged in later El Niño events, contaminating shellfish and causing the illness in thousands.

Comparing bacteria strains

The scientists then used data derived from the sequencing of these different bacterial strains, which they compared to strains present in Asia. Their analysis highlights a link between the pathogens, in both regions of the world, suggesting that the bacteria may have travelled with El Niño, "piggybacking" on the ocean currents to reach new shores.

"We suggest that so-called vibrios can attach to larger organisms, such as zooplankton, to travel oceans. Numerous previous studies have shown how such vibrios bind to and use these larger organisms as a source of energy and through this mechanism, we suggest, they are essentially able to piggyback to travel such enormous diseases, driven by ocean currents," says lead author Dr Jaime Martinez-Urtaza.

They believe their findings have important public health consequences and could help authorities in countries most affected by El Niño to prepare better for potential disease outbreaks.

"An El Niño event could represent an efficient long-distance 'biological corridor', allowing the displacement of marine organisms from distant areas. This process could provide both a periodic and unique source of new pathogens into America with serious implications for the spread and control of disease," concludes co-author Dr Craig Baker-Austin.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.