Commercial US Spaceship Lands On Moon, A First For Private Industry

A Houston-based company has landed America's first spaceship on the Moon in more than 50 years, part of a new fleet of NASA-funded, uncrewed commercial robots intended to pave the way for astronaut missions later this decade.

A Houston-based company has landed America's first spaceship on the Moon in more than 50 years, part of a new fleet of NASA-funded, uncrewed commercial robots intended to pave the way for astronaut missions later this decade.

But while flight controllers confirmed they had received a faint signal, it was not immediately clear whether Odysseus, the lander built by Intuitive Machines, was fully functional, with announcers on a live stream suggesting it may have come down off-kilter.

The hexagon-shaped vessel touched down near the lunar south pole at 2323 GMT, having slowed from 4,000 miles (6,500 kilometers) per hour.

Images from an external "EagleCam" that was supposed to shoot out from the spacecraft during its final seconds of descent could be released.

For the time being, however, nothing is certain.

"Without a doubt our equipment is on the surface of the Moon and we are transmitting," said Tim Crain, the company's chief technology officer. "So congratulations IM team, we'll see how much more we can get from that."

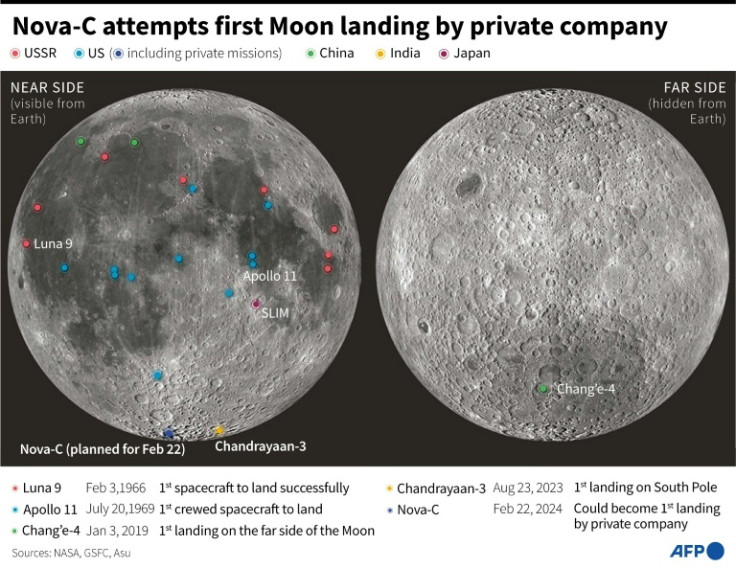

A previous moonshot by another American company last month ended in failure, raising the stakes to demonstrate that private industry has what it takes to repeat a feat last achieved by US space agency NASA during its manned Apollo 17 mission in 1972.

The current mission "will be one of the first forays into the south pole to actually look at the environmental conditions to a place we're going to be sending our astronauts in the future," said senior NASA official Joel Kearns.

"What type of dust or dirt is there, how hot or cold does it get, what's the radiation environment? These are all things you'd really like to know before you send the first human explorers."

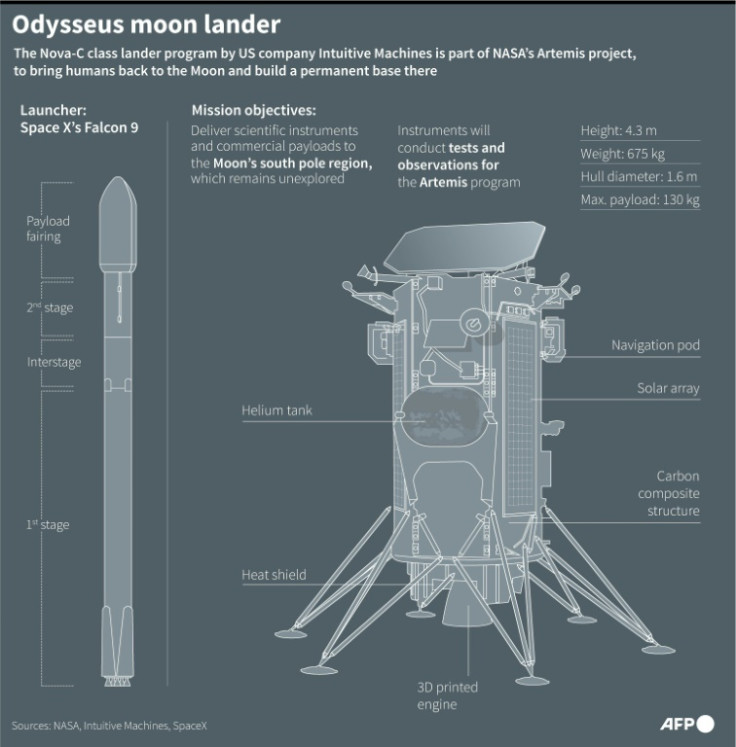

Odysseus launched February 15 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and boasts a new type of supercooled liquid oxygen, liquid methane propulsion system that allowed it to race through space in quick time.

Its landing site, Malapert A, is an impact crater 300 kilometers (180 miles) from the lunar south pole.

NASA hopes to eventually build a long-term presence and harvest ice there for both drinking water and rocket fuel under Artemis, its flagship Moon-to-Mars program.

Instruments carried on Odysseus include cameras to investigate how the lunar surface changes as a result of the engine plume from a spaceship, and a device to analyze clouds of charged dust particles that hang over the surface at twilight as a result of solar radiation.

It also carries a NASA landing system that fires laser pulses, measuring the time taken for the signal to return and its change in frequency to precisely judge the spacecraft's velocity and distance from the surface, to avoid a catastrophic impact.

This instrument was meant to run as a demonstration only, but Odysseus eventually had to rely on it for the entire descent phase of its journey, after its own navigation system stopped working -- forcing controllers to upload a software patch to make the switch.

The rest of the cargo was paid for by Intuitive Machines' private clients, and includes 125 stainless steel mini Moons by the artist Jeff Koons.

There's also an archive created by a nonprofit whose goal is to leave backups of human knowledge across the solar system.

NASA paid Intuitive Machines $118 million to ship its hardware under a new initiative called Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS), which it created to delegate cargo services to the private sector to achieve savings and stimulate a wider lunar economy.

The first CLPS mission, by Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic, launched in January, but its Peregrine spacecraft sprung a fuel leak and was eventually brought back to burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

Spaceships landing on the Moon must navigate treacherous boulders and craters and, absent an atmosphere to support parachutes, must rely on thrusters to control their descent. Roughly half of the more than 50 attempts have failed.

Until now, only the space agencies of the Soviet Union, United States, China, India and Japan have accomplished the feat, making for an exclusive club.

© Copyright AFP 2025. All rights reserved.