Damning report finds 'basic IT security' could have stopped NHS WannaCry cyberattack

The National Audit Office (NAO) spearheaded NHS probe.

The UK's National Health Service (NHS) could have prevented the unprecedented 'WannaCry' malware outbreak earlier this year if it had applied basic IT procedures and heeded warnings from security experts to apply software upgrades, a government report stated Friday (27 October).

The National Audit Office (NAO) spearheaded an investigation into NHS response to the cyberattack, the most widespread to hit the healthcare service.

"[WannaCry] was a relatively unsophisticated attack and could have been prevented by the NHS following basic IT security best practice," NAO chief Amyas Morse said in the statement.

"There are more sophisticated cyber threats out there than WannaCry so the Department of Health and the NHS need to get their act together to ensure the NHS is better protected against future attacks."

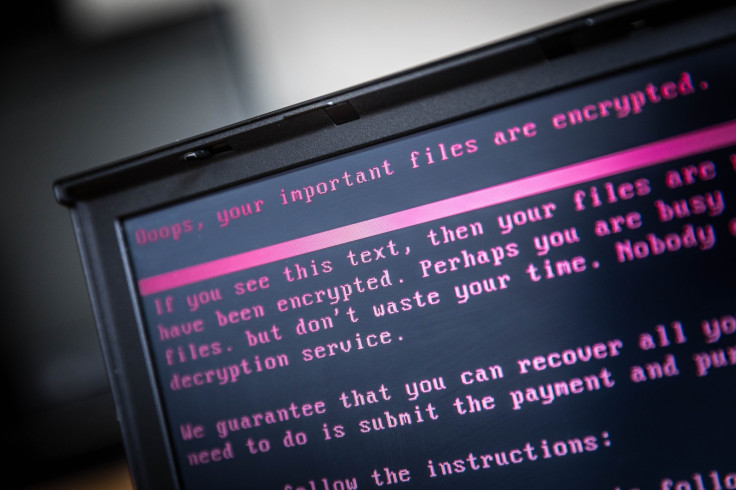

On 12 May, WannaCry, which encrypted data on infected computers and demanded a ransom payment to allow users access, affected 300,000 computers worldwide.

It eventually spread to approximately 150 countries and was later linked, by multiple cybersecurity companies, to hackers aligned with North Korea.

The report said at least 81 out of 236 trusts across England were affected. A further 603 primary care and NHS organisations were infected, including 595 GP practices.

But the probe found that the Department of Health had warned the NHS about the risks of cyberattacks a year before the incident took place.

It also said that in March and April this year, regional NHS health Trusts failed to patch their computer systems with the fixes that would have stopped WannaCry from spreading – despite being informed of the updates by NHS Digital.

NHS Digital told the probe that all organisations infected by WannaCry shared the same vulnerability and could have taken simple action to protect themselves.

Infected organisations had unpatched, or unsupported Windows operating systems making them susceptible to the ransomware, which spread with the help of a leaked computer exploit from the National Security Agency (NSA).

Thousands of appointments and operations were cancelled and in five regions patients had to travel longer distances to accident and emergency (A&E) departments.

NHS England identified 6,912 appointments had been cancelled, and estimated over 19,000 appointments would have been shelved in total. Neither the Department of Health nor NHS England know exactly how many GP meetings were scrapped.

It is believed that no NHS organisation paid the ransom demand, but the healthcare service still incurred significant costs as a result of the cyberattack, it said.

These costs included cancelled appointments, IT support provided by NHS local bodies, hired IT consultants and the restoration of data and networks.

The Department of Health had reportedly developed a plan, which included "roles and responsibilities of national and local organisations for responding to a major cyberattack", but had not tested the plan at a local level, the report said.

As the findings were released to the public, UK security minister Ben Wallace said it is "widely believed in the community and across a number of countries that North Korea" was responsible.

The cyberattack could have caused more disruption had it not been stopped by a researcher who activated a 'kill switch' that prevented WannaCry spreading. It was halted, admittedly by accident, by a 22-year-old coding expert called Marcus Hutchins.

NHS England and NHS Improvement claim to have now written to "every major health body" asking boards to ensure that they have implemented all alerts issued by NHS Digital between March and May 2017 and taken action to better secure local computers.