The darker side of Stardew Valley: Escapism and humanity in 2016's hit country-life farming game

Reading between the lines of Eric Barone's love letter to Harvest Moon and other Nintendo classics.

"There will come a day when you feel crushed by the burden of modern life... and your bright spirit will fade before a growing emptiness." Stardew Valley opens with this line, uttered by a bearded elderly gentleman on his death bed.

Stripped of the twinkling, melancholic music track and the game's pixelated, technicolour art-style, these last words uttered by your avatar's grandfather appear uncharacteristically bleak for a game in which you'll spend an obscene amount of hours watering and harvesting root vegetables.

Eric Barone's (a.k.a. ConcernedApe) obscenely dense country-life game is full of darker, more contemplative moments like this, slipped in under the shadow of its twee, happy-go-lucky aesthetic – but this first one is crucial.

On a surface level, Stardew Valley and games of its ilk are exercises in pure, mindless escapism. Barone's PC hit (later releasing on PS4 and Xbox One, with a Nintendo Switch launch due in 2017) addresses this idea in its broadest strokes, depicting the idyllic, rural village as a literal escape from the player character's day-to-day job stuck inside a dank, cubicle farm run by the gluttonous mega-corporation Walmart... sorry, JojaMart.

Judging by the game's surprise popularity and the triple digit hour-playtime stat on my Steam profile (split between my bonafide Stardew-addict fiancé and I), it seems that many of us were more than willing to follow in our avatar's footsteps and stick around for the long haul.

This is partly thanks to the daily-to-weekly-to-seasonal design which effortlessly combines the vast amount of agricultural busy-work from the genre-classic Harvest Moon series with Animal Crossing's simple collect-athon gameplay and Minecraft-like crafting mechanics. Stardew Valley walks a delicate line with this enslaving gameplay loop however, threatening to turn into an enslaving burden of its very own with every passing hour spent in its obsessive grasp.

Barone's creation avoids this trap that so many RPGs (both country-life and otherwise) fall into by peppering its repetitive gameplay structure with a human element.

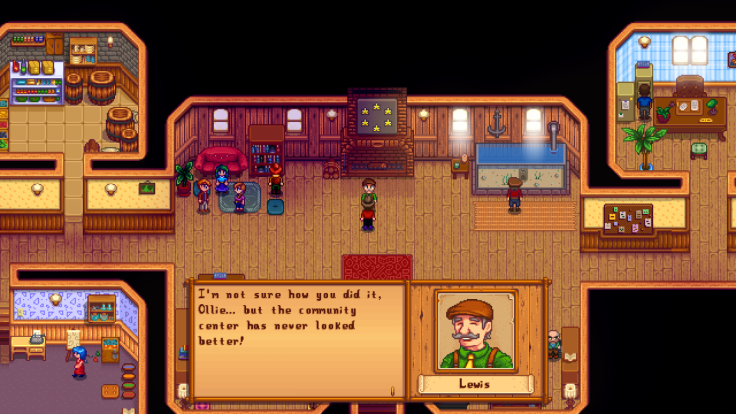

When you finally reach your plot you are faced with a daunting sight – an overgrown, unkempt field of trees, bushes, rocks and weeds. Yet, while you can pick up and axe and start the renovation project immediately, it's telling that Stardew Valley's slightly mawkish mayor, the ever-cheery Lewis, recommends your first act as a resident of Pelican Town should be introducing yourself to the townsfolk.

At its heart, Stardew Valley is a game about community – an idea that's hammered home by the main objective of the game's "good path", i.e. restoring the dilapidated Community Centre to its rustic former glory (with the help of a bunch of tiny forest spirits, of course).

As you come to learn more about each resident, you discover that almost every character in Stardew Valley is wrestling with personal demons of some kind. This has resulted in a fragmented population of disparate races and creeds where genial tolerance and responsibility for the village's upkeep –shopkeeper, blacksmith, doctor, mayor – supersedes genuine happiness and harmony.

Distance – both emotional and physical – is a common theme in the majority of the NPC-specific side-stories: Introverted loner Sebastian spends most of his time sat behind a computer, planning his escape from a dull existence via a programming career and his beloved motorcycle. Leah hides out in her cottage, crafting (admittedly rubbish) sculptures, afraid to present her work to the town and struggling to cope with phone calls from an ex-partner who brands her decision to move away from the city as "selfish."

Most of these stories have a fairly straightforward resolution, with several including fun one-off mini-games (particularly the brilliant Dungeons and Dragons-style role-playing session), but the subject matter takes a darker turn with certain characters, each without a simple solution.

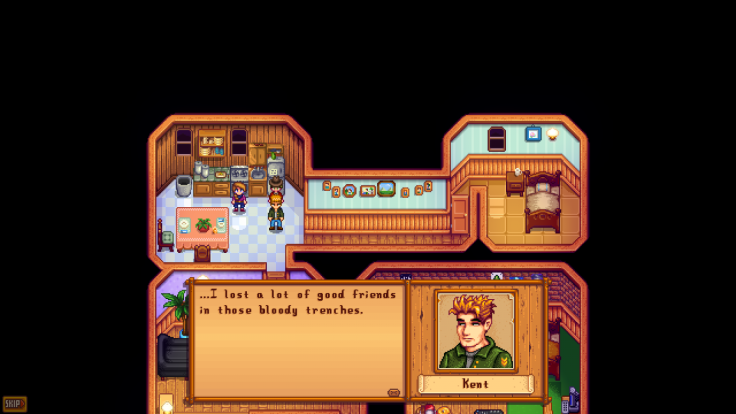

Elderly curmudgeon George eventually opens up about the mining accident that left him unable to walk, explaining that no one has asked him about it for some time as few people spare any to those of his generation. In the second year, Jodi's husband, Kent, returns to Pelican Town after a stint in the army, with a later cutscene revealing that Kent he has severe Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and struggling to rekindle a relationship with his son, Sam. Even Alex – a sporty lad who won't shut up about sports – is quietly suffering in silence, suppressing memories of his late mother and abusive father.

Much of the incidental dialogue from the villagers implies that the appearance of a JojaMart store was catalyst for the loss of a communal atmosphere among the townsfolk, and the faceless, charmless supermarket chain looms large over Pelican Town, despite the fact that the local store sits off to the east, outside the main part of the map.

You can actually buy into the corporate regime should you wish by entering into a clandestine arrangement with shady JojaMart store owner Morris – a decision that replaces the Community Bundle challenges with a hollow pay-to-win (using in-game currency) tick-sheet. Completing this set dooms the Community Centre and Pierre's struggling local shop for good, although I had to look this scene up as I've struggled to find anyone who actually picked this route – even with the allure of cheaper seed prices.

Most poignant however, is JojaMart's role in the life of Stardew Valley's best side-story. When you first enter Pelican Town, most will see Shane first, clad in blue overalls, pacing slowly toward the JojaMart store for the start of his grueling 8am-5pm shift. After the slew of warm welcomes from the majority of the town's colourful cast, his initial dialogue response is jarringly hostile: "I don't know you. Why are you talking to me?"

Persistence pays off at first and his mood around you eases over time, but it's hard not to notice how Shane frequents the Stardrop Saloon almost every night, each time clutching a pint glass. Cutscenes later reveal that Shane loathes almost every part of his life, alienating potential friends in the community and causing endless worry for his family in the process.

Shane's inferred struggle with depression and his resulting suicide attempt are dealt with in an honest manner, showcasing the game's maturity and sincerity underneath its whimsical surface and reveal a great deal about Stardew Valley's central theme.

These deeply personal interludes transform an at-a-glance, run-of-the-mill Harvest Moon clone into a fable of sorts, complete with a tender moral lesson teased in the first five minutes of the game inside the grandfather's letter:

"You must be in dire need of a change. The same thing happened to me, long ago. I'd lost sight of what mattered most in life... real connections with other people and nature."

Escapism, we are told, can be a blessing in dark times, but we shouldn't ever confuse it with isolation, and in a year as grim and divisive as 2016, an escape to Stardew Valley was the perfect escape.

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.