Deadly stickers laced with fentanyl look like they're for children

KEY POINTS

- Fentanyl stickers are the latest horror to emerge from the US opioid crisis.

- Donald Trump has declared opioid epidemic a national health emergency.

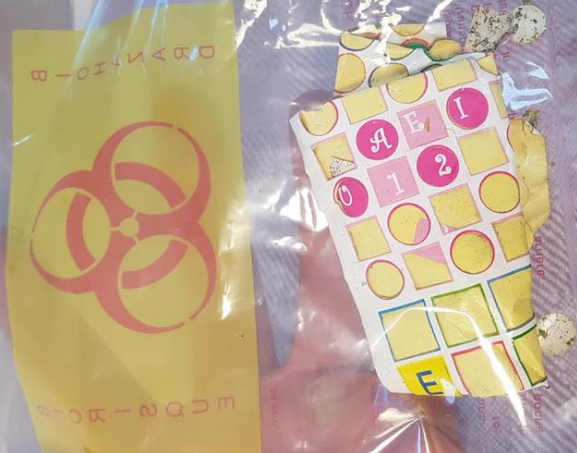

The stickers look like they came free with a children's magazine. In fact, they contain potentially lethal doses of fentanyl – the super-strength opioid wreaking havoc in towns across North America.

The pink, cutesy patches, which could easily be mistaken for a kids' play activity products, are the latest horror to emerge from a drugs death epidemic claiming thousands of lives.

US law enforcement are on high alert for the sinister product, which Canadian authorities believe claimed at least two lives earlier this year. More than 20,000 Americans died of synthetic opioid overdoses in 2016 – a four-fold increase on 2014.

Fentanyl drug is 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin and as little as a few grains can be fatal. On the black market it is often used to strengthen injectable heroin, resulting in many deaths because end users do not know how strong each mixture is.

The patches look like "something that a three-year-old would put into a colouring book," Dr. Mark Yarema, a Canadian physician, told the Ottawa Citizen back in August.

"The amount of drugs and the number of drugs could vary from sticker to sticker... you're playing Russian roulette and you have really no idea what you're getting into," he added.

Yarema stressed that a final analysis of the stickers had not yet been carried out – but he believed that a pair of recent deaths were linked to them.

Ironically, when fentanyl is legally prescribed as a pain reliever for cancer patients, it is commonly in a slow-release patch put on the skin. But these are produced in professional laboratories and users can trust the doses on the label. A dosage guide is absent on the pink stickers.

The patches resemble tabs of LSD, or 'blotters', which are made when a solution of the drug is soaked into sheets of paper on the assumption that the solution will spread uniformly throughout each sheet.

"These are not produced in high-quality pharmaceutical labs with stringent quality control," Yarema said.

"The faster way to get the effect would be to eat the patch and that's what people have done in terms of abusing the proper fentanyl patches. They simply eat them and the effects are within 30 to 60 minutes, tops."

The US opioid epidemic and the pharmaceutical industry

Around 64,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in 2016 – almost twice as many as a decade ago. At the heart of this troubling statistic is a vast number of people addicted to opioids.

In the 1990s, the pharmaceutical industry flooded the healthcare system with opioid pain relievers like Oxycontin and assured clinicians they were not become addictive. That assurance turned out to be false, giving rise to a generation of opioid-dependent Americans, many of whom turned to heroin as regulations on painkillers became more stringent.

The user group is now more vulnerable than ever as fentanyl, often manufactured in China, has started to flood the heroin market, leading Donald Trump to describe the staggering number of deaths as a "national healthcare emergency".

But it would be wrong to assume that the pharmaceutical industry's role in the epidemic was consigned to the distant past. The pharma giant Insys Therapeutics Inc has been sued by several states for fraudulently prescribing fentanyl to patients who did not need it this decade.

John Kapoor, the billionaire founder of Insys has also been arrested and charged for his alleged role in the crisis, which saw his employees lie to doctors and bribe them in order to boost the sales of Subsys, a fentanyl patch, Reuters reported. He strongly denies the charges.