From delivering emergency medicine to animal conservation: Flying drones save lives in Africa

IBTimes UK meets the teams using drones to combat wildlife crime in South Africa, Malawi and Zimbabwe.

First used for humanitarian purposes in a number of countries across Africa, including Rwanda, Madagascar and Uganda, drones are also becoming an essential tool to combat poaching and protect endangered species in Southern Africa.

The world's first unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) delivery service was launched in mid-October in Rwanda, where drones are used to deliver blood and emergency medicine to doctors and nurses in remote areas of the country. A similar service was carried out in Madagascar, this time for blood and stool samples. The Red Cross launched an initiative in Uganda in September using aircraft to monitor the humanitarian situation at a vast refugee camp on the border with South Sudan.

In Southern Africa, the UAVs are now used to save endangered animals, and the timing could not be more critical. Demand for elephant ivory and rhinoceros horn, fuelled by economic development in markets such as China and Vietnam, has sent poaching rates soaring.

NGO Save the Elephants estimates that, between 2010 and 2014, the wholesale price of raw ivory in China tripled, reaching $2,100/kg, meaning that across Africa, an elephant is killed every 14 seconds.

By the end of 2015, the number of African rhinoceros killed by poachers had increased for the sixth year in a row, according to the Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission's African Rhino Specialist Group (AfRSG).

In order to reduce poaching rates in Southern Africa, the Lindbergh Foundation reached out to UAV and Drone Solutions (UDS), a developer of drone solutions, as it sought out to extend its Air Shepherd program. Designed to protect these endangered species that wildlife campaigners say could be extinct within the next decade, the program began its operations in South Africa in December 2015.

Last month, Air Shepherd launched two drone programmes with financial assistance from World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in Malawi and Zimbabwe, under which 16 pilots fly 25 licensed drones.

'We don't want to be seen, and we don't want to be heard'

Operating in threes across Southern Africa's national parks, gangs of night-poachers typically shoot animals with a heavy-caliber rifle in the last light, and hack off the horn or ivory before exiting the park under the cover of darkness after rangers of the anti-poaching operations have gone home. Using another deadly tactic, poachers poison watering holes frequented by elephants with cyanide.

"Historically, there has been very little ability for an anti-poaching operation to work at night. One - you can't see tracks, it's difficult to see people and it's dangerous because the anti-poaching teams can walk onto elephants, rhinos or buffaloes," Otto Werdmuller Von Elgg, director of UDS, which is supplying the drones, told IBTimes UK in South Africa.

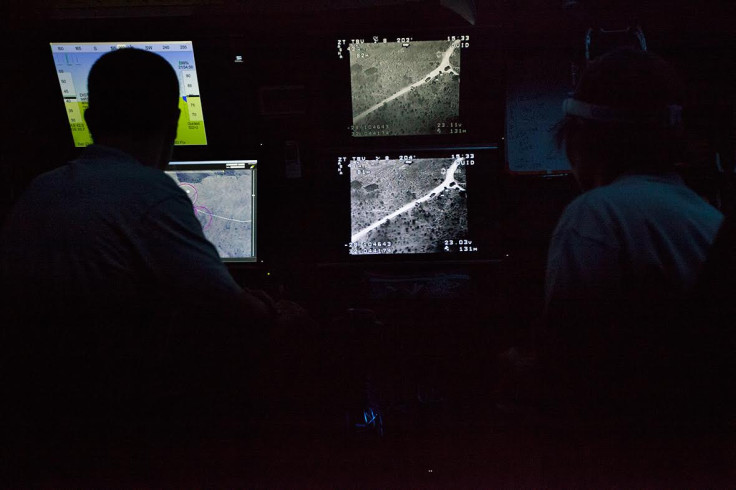

To overcome this challenge, 3m (9.84ft) wingspan drones equipped with infrared cameras fly at night for a distance of up to 25km (15.5mi) away from the teams manning the UAVs. The teams monitor the video feed from the aircraft from command vehicles parked either inside or outside the parks.

"That's unique because, for instance in the UK, you are strictly prohibited from flying this kind of machine at night, and you are not allowed to fly it beyond the vision line of sight (defined at 500m, 0.31mi)," Werdmuller Von Elgg added. "By being able to tell [rangers] where they can or can't walk, we can give them the security to operate at night, which they have never had to date."

The anti-poaching operators can use the drones in three ways to augment the limited police presence in these parks. Because the small fixed wing aircraft are silent, the teams can fly them in a completely covert manner across the vast wildlife reserves, and instantly inform rangers of the location of criminals. "We don't want to be seen, and we don't want to be heard," the director said.

Secondly, if the teams come across poachers operating under the cover of night, pilots have the ability to fly lower and switch on their lights in order to scare the poachers into leaving the park, which allows rangers to intercept suspects before a poaching incident can take place.

The programme has had success. Thermal footage provided to IBTimes UK by UDS shows three dots moving fast across the bush, away from the drone - a giveaway since poachers work in threes: a tracker, a shooter and a carrier.

"The clip shows those guys being chased - it was a hot pursuit because there were gun shots fired: they were running like hell to get out (of the park) as quickly as possible," Werdmuller Von Elgg explained.

Using drones to fight poaching, illegal fishing and logging

In Zimbabwe and Malawi, operations are carried out in a different manner. In Zimbabwe, where UDS works directly for the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority, drones are flown in the daylight because the area faces more from daytime poaching. Teams in Malawi deal with night-time elephant poaching, illegal fishing and logging, spearheaded by the conservation NGO African Parks, which has management responsibility for Liwonde National Park.

Fighting illegal fishing is relatively easy, Werdmuller Von Elgg says, because boats and canoes are easy to spot on water. "If we saw them, we can act in two different ways. We could fly covert and assist a boat that would go and apprehend them, or we could switch lights on and display that they have been seen, before we link that to some action on the ground." While infrared images mean the teams can not distinguish facial features, videos could be produced in court as evidence.

Local residents play an increasingly large role in the anti-poaching campaign. When they hear that the drones are flying in an area, villagers spread the word - which effectively halts poachers who, the activists say, do not know what to make of the drones, which they usually associate with military activity.

"We need to provide this service where there is no way of dealing with the poaching circumstance - if you have to be quiet or you are in a very dangerous area, and there is no other tool to use, that's when a drone should be used," Werdmuller Von Elgg said.

He expects other governments and organisations to turn to drones as tools once they become faster, more affordable and easier to fly in sub-optimal weather conditions.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.