Do sharks ever sleep?

Sharks do not have eyelids and are thus never going to appear asleep as we would expect.

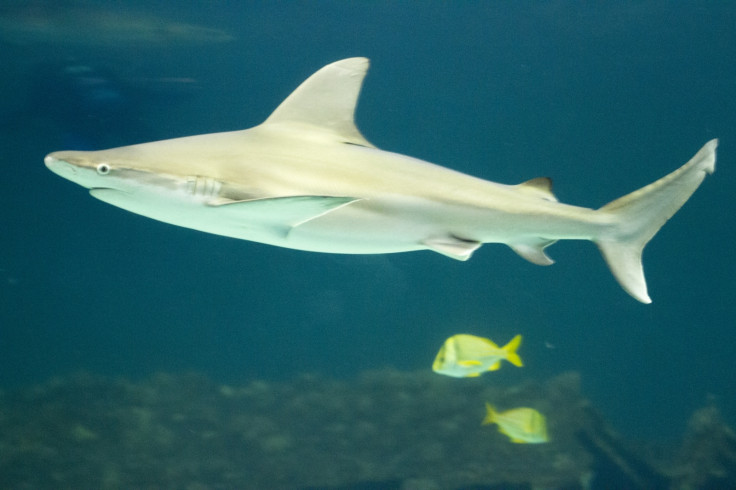

Sharks and their sleep patterns are still very much a mystery, although the question of whether sharks really sleep comes down to how you define sleep. We can identify sleep in many animals because they act in a manner similar to humans when sleeping. For example, dogs lie down, close their eyes and even twitch their feet when in a dream-like state. But how do you recognise a sleeping shark?

According to the Macquarie Dictionary, sleep is defined as "to take the repose or rest afforded by a suspension of the voluntary exercise of the bodily functions and the natural suspension, complete or partial, of consciousness". In other words, when asleep you are less aware of your surroundings, you have less control over your physical motions, and your rate of physiological functioning decreases.

Another definition by the same dictionary is that to be asleep is "to be unalert or inattentive", also suggesting a reduced power of comprehension of the external environment.

What does this mean for sharks? Traditionally considered perpetually on the go, it was widely thought that sharks had to keep constantly moving to force water over their gills to 'breathe'.

We now know that some sharks, particularly bottom-oriented (benthic) species like cat sharks, nurse sharks and wobbegongs 'rest' by lying in caves or on the sea floor.

During these periods of rest, they are able to actively breathe by pumping water through their spiracles (nose-like structures) and through their mouths and gills. Such pumping is related to a low/no swimming rate and respiration. To me, this suggests that at least some bodily functions and physiology are reduced during this sleep-like state.

The concept of consciousness is currently one of the hot topics in fish ecology. The difficulty lies in trying to directly measure a conscious sensation in an animal. As sharks are essentially big fish, these arguments are pertinent here. Most behavioural approaches to this problem can only infer a conscious state.

Aspects of behaviours that imply consciousness (at least in other types of animals) have been studied to tease apart this issue for sharks and other fish. Whether a fish is conscious of the feeling of pain or whether it is merely detecting a painful negative sensation is one example. Although still controversial amongst some, it is generally accepted that fish feel pain.

Studies have shown that fish can be conscious of suffering in a manner similar to birds and mammals, and research on shark physiological processes show that they can also feel stress.

Other studies show that sharks may even have personalities. It should be said, however, that the physiological aspects of pain and stress do not automatically mean that these are conscious mechanisms.

If sharks have such a similar and diverse range of traits that parallel ours such as these, however, the question should really be: "why shouldn't sharks have a level of consciousness?"

Back to the sleep question. Sharks do not have eyelids and are thus never going to appear asleep as we would expect. Behaviours of both benthic and oceanic species do suggest a regular sleep-like pattern. Oceanic species such as mako and blue sharks swim to the surface then drift slowly back towards deeper waters. During the sinking step of this behaviour, coined "yo-yo diving behaviour" one hypothesis as to one of the causes of this behaviour is that the sharks conserve energy and 'rest'.

Whether this energy conservation akin to resting occurs in all pelagic species, or whether this 'resting' stage is anything analogous to sleep, is at this stage anyone's guess.

Jane E Williamson is an Associate Professor in Marine Ecology in the Department of Biological Sciences at Macquarie University, Australia. You can find her on Twitter at @urchinhunter.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.