Do Trade Sanctions Work? One Economist Tackles a Question for our Time

A new report by a respected economist has cast a shadow over the efficacy of trade sanctions.

Jamal Ibrahim Haidar of the Paris School of Economics has just completed a study entitled Sanctions Backfire: Did Exports Deflection Help Iranian Exporters? It investigates the portion of sanctioned Iranian goods that were simply exported to new destinations when their route to western markets were closed off.

IBTimes UK has seen a draft of the study and the conclusion is stark: "Export sanctions may be less effective in a globalised world as exporters can deflect their exports from one export destination to another."

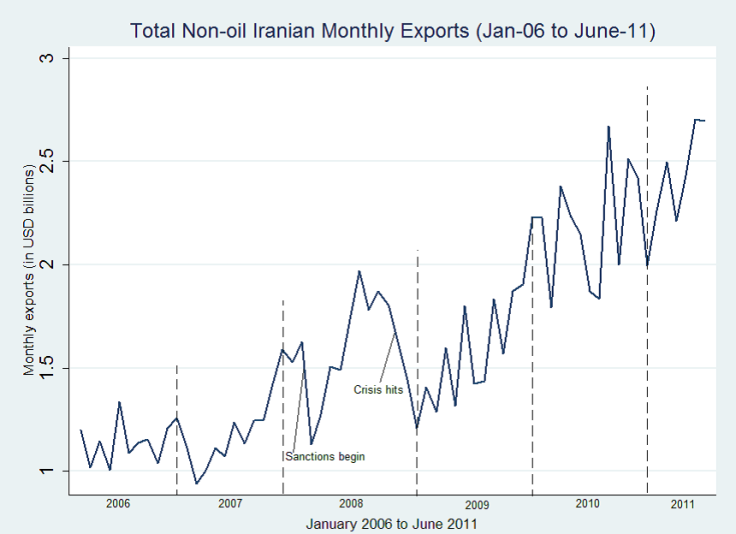

Haidar studied the data from non-oil transactions that were completed under the scything sanctions regime the West imposed on Iran. The dataset covers the period spanning January 2006 to June 2011 and includes details on 1.81 million transactions, logged on a daily basis.

While oil is the dominant sector in the Iranian economy, Haidar chose to study non-oil transactions for a number of reasons: first and foremost, because overseas oil companies were only really forced to stop buying from Iran in 2012.

Furthermore, despite accounting for 80% of Iran's exports, there is only one oil exporter in Iran: the state-owned National Iranian Oil Company. There are, on the other hand, more than 35,000 non-oil exporters, accounting for 38% of total employment, compared with 0.7% at the oil utility.

Haidar, who formerly worked at the World Bank, Deloitte and UNESCO, found that "two-thirds of the value of Iranian non-oil exports thought to be destroyed by exports sanctions have actually been deflected to destinations not imposing sanctions".

Not only that, he discovered that non-oil exports actually increased under the period studied. Iranian exporters largely had to reduce the prices of their goods and, obviously, find new customers in Iranian-friendly countries, but the message, which is pertinent in the current economic and political climate, is clear: trade sanctions need not signal the death knell for a country's exports sector.

It's a vital message for companies in the UK and wider EU as much as for those in Russia. Part of the EU's reluctance in imposing the latest set of sanctions on Moscow was the value of trade the EU would stand to lose.

The study suggests that the lag could potentially be picked up by alternative markets, particularly if European exporters are willing to show some price elasticity.

The moral of the story holds for Russia too. Already analysts are speculating which markets stand to benefit from the gap in the Russian market left by the West.

After Russia slapped a retaliatory ban on the import of most foodstuffs from the EU and US, as well as Australia, Canada and Norway, around 90 new Brazilian meat plants were approved to sell chicken, beef and pork to Russia, with Brazil also hoping to increase its exports of corn and soybeans to Russia, according to its secretary of agricultural policy, Seneri Paludo.

Moscow was also said to have been meeting with representatives of other Latin American governments last week to further diversify its trade routes.

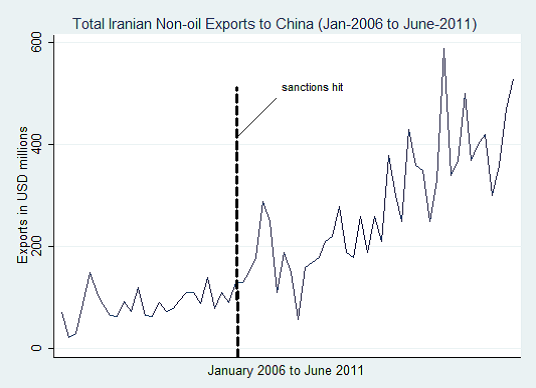

It's a move which mirrors the strategy assumed by Iran post-2008. After sanctions hit Iran, non-oil exports to China, Brazil, Nigeria, South Africa, India and Afghanistan increased at a greater velocity to the slump in trade with western markets (see below).

Why Did Iran Negotiate?

Last year I conducted an interview with Tom Pickering, the former US ambassador to, among others, the UN, Russia and Israel, when he was on a visit to London. He said that it was only once Iran was excluded from the international banking system in 2012 that sanctions really began to bite and when policymakers in Tehran felt they needed to sit down and talk.

Iran had been banned from using the SWIFT network, through which traders around the world send and receive information about financial transactions. Even for those traders in countries which were permitted to trade with Iran, if they used the SWIFT network, they were unlikely to continue doing business with those Iranian companies that were excluded from it.

Russian companies have yet to be banned from using SWIFT and, unless we see a drastic escalation in hostilities, are unlikely to be in the near future.

The country's state-owned banks and companies have, however, been banned from raising capital on the European markets, excluding them from the debt and stock markets in London, Paris and so on.

These financial sanctions may well be more crippling than the trade embargoes. Already, Russian firms are expected to face difficulties in refinancing debt facilities which are due to mature over the coming years. According to a report by Moody's Investors Service released in July, Rosneft has $112bn in debt due to mature over the next four years, with the bulk expiring next year.

Barred from raising debt on the European markets, it will find it extremely difficult to replace the facilities. Russian domestic banks also commonly visit European markets to raise debt and since the government holds a majority stake in most of them, the likes of Rosneft finds itself in a double bind.

Russia may have alternative fundraising options in the East but the coming months may serve to prove the hypothesis that's implicitly suggested in this paper: that financial sanctions are more effective and punitive than any trade sanctions, no matter how scything the latter may seem.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.