E. coli turned into factories to make new versions of antibiotic

Scientists have succeeded in the first step towards using bacteria in the fight against bacteria.

Researchers from the University of Buffalo have engineered colonies of the bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli) to produce antibiotics that also work against drug-resistant bacteria.

By virtue of their rapid growth rate, ease of genetic manipulation and scalability, bacteria offer an advantage over other forms of drug manufacture.

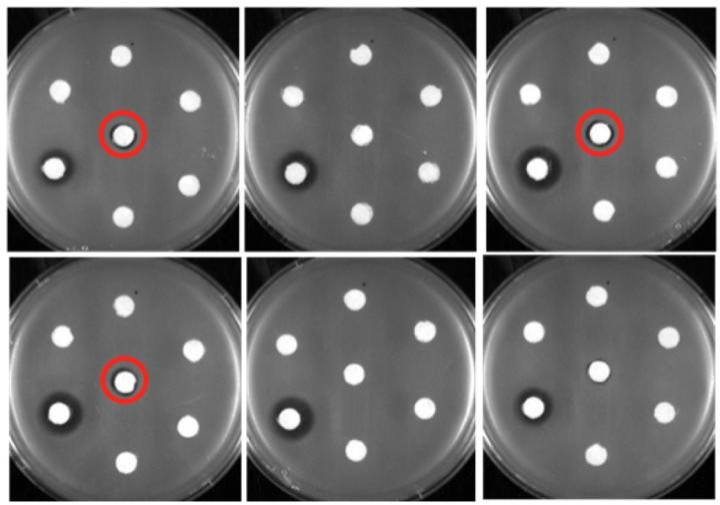

Led by Blaine A Pfeifer, an associate professor of chemical and biological engineering in the University at Buffalo School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, the team could make more than 40 new analogs of erythromycin — three of which killed erythromycin-resistant bacteria in lab experiments.

Erythromycin is used to treat a variety of illnesses, from pneumonia and whooping cough to skin and urinary tract infections.

The research is published in the journal Science Advances.

For more than a decade, the team has been studying how to engineer E. coli to generate erythromycin. The latest work addressed versions of the antibiotic different from those in use.

The process begins with combining three basic building blocks called metabolic precursors in an assembly line technique to form the final product, erythromycin.

For new varieties of erythromycin, parts with slightly differing structures are placed at various points on the assembly line.

Technique used

In the new study, Pfeifer's team focused on using enzymes to attach 16 different shapes of sugar molecules to a molecule called 6-deoxyerythronolide B at the end of the assembly line. The new forms of the drug have a slightly different structure from existing versions.

"We have not only created new analogs of erythromycin, but also developed a platform for using E. coli to produce the drug," he said. "This opens the door for additional engineering possibilities in the future; it could lead to even more new forms of the drug."

Most types of E coli are harmless, including those used by Pfeifer's team in the lab.

The study is important in the context of rising drug resistance by bacteria and other pathogens. The WHO has called for a global action plan to combat the biggest health threat of the century.

More people die from antibiotic-resistant bacteria than from traffic accidents in Europe.

Despite the need for new antibiotics, only two new antibiotics have been approved since 2009. Big pharma are not interested as the returns are low.

The last one to be introduced was ceftaroline in 2010 but within a year gave rise to drug resistant staph germ.

Globally, antibiotic use has risen by 36% during the last decade. Prescription of the drugs for a wide range of viral infections as also availability over the counter, and overuse in veterinary medicine, has led to development of drug resistant strains of microbes.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.