Egypt: Oldest known gospel found in mummy mask - what's really going on?

The oldest known fragment of a New Testament gospel has been found in a mummy mask, a story IBTimes UK highlighted on 19 January, citing comments made by biblical scholar Dr Craig Evans to Live Science.

The resulting media furore has made it a key talking point with archaeologists, Christians and lots more people around the world, so we decided to delve deeper.

Here's what we know so far:

- Many of the details about this find are vague – no one knows where the mask comes from, except that it belongs to the Green Collection, the world's largest private collection of rare biblical texts and artefacts.

- No research has been published – it was supposed to make an appearance last year but now will not be out until at least 2017, according to Evans – and there are no pictures of the papyrus fragment either.

- Non-disclosure agreements have been signed so no one in the Green Collection or the Green Scholars Initiative can release any details about the papyrus fragment or the mummy mask.

There are also two important issues at stake that many archaeologists have a strong opinion about: is it ethical for priceless ancient artefacts to be dismantled in order to access fragments of papyrus, and is it ethical to acquire artefacts for study via the black market or private collectors?

The significance of this find, if it is real

Dr Roberta Mazza is an ancient historian and papyrologist from the University of Manchester in the UK.

She has been following the news about the gospel papyrus fragment since it was leaked in 2012 by Daniel Wallace, founder of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts at Dallas Theological Seminary.

"To find a new manuscript of Mark is something very important in the study of the New Testament, but to find manuscript in mummy masks would also be a revolution about what we know about mummy cartonnage," Mazza told IBTimes UK.

"Up until now, we haven't found even one papyrus coming from mummy cartonnage that dates to a period after Emperor Augustus [27 BC – 14 AD]. If we were to find something dated to a later date, that would be fantastic, but it has never happened before because Egyptian burials changed after that time."

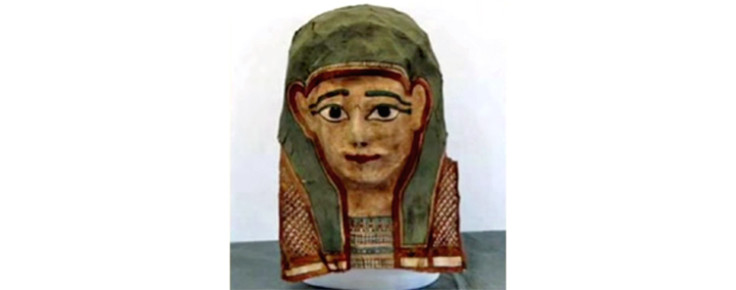

The phrase "mummy cartonnage" is implied by archaeologists to mean a type of papier-mâché used to fabricate any kind of mummy masks or panels used to decorate the mummy.

A variety of materials were used to create mummy cartonnage, including linen, papyrus and textiles. These were usually reinforced with layers of plaster and then moulded on to the face or body of the deceased to make cases, masks or panels to cover all or part of the mummified body.

Is it OK to dismantle ancient artefacts?

Evans, a professor of New Testament studies at Acadia Divinity College in Nova Scotia, Canada, is at the centre of the current furore due to comments he made about the fragment during a talk to the 2014 Apologetics Canada conference and his subsequent interview with Live Science. However, he says he has never seen the papyrus fragment before.

His research primarily focuses on how long biblical books have been in circulation and he says he only mentioned it in his talk to support his argument about how if this fragment is for real, it means the Gospel of Mark would have been used 20 years earlier as a complete book.

Evans' study into the circulation of biblical books has been peer-reviewed and has been accepted for publication in the Bulletin for Biblical Research, in its Volume 1, 2015 issue, which is out in two months' time.

He also does not think it is unethical to destroy mummy cartonnage in order to get to papyrus fragments.

"As I understand it, there are thousands of these mummy masks and various shapes and sizes of cartonnage [crocodiles, other types of animals, figures and the like]," he told IBTimes UK.

"Many of them are in poor condition, either from exposure to the elements or to vermin, or whatever. Some likely suffered damaged from rough handling.

"Some are well enough preserved but they are very poorly made and the artwork is quite shabby. These are the specimens that are being deconstructed in order to recover the papyri."

Evans says it is sometimes necessary to dig beneath one historical layer at an excavation in order to access an even more ancient layer of artefacts below it.

He said: "Stratigraphy literally means measuring layers, strata in the ground. The deeper you go, the older it is.

"In a layer of excavation, let's say you're in a layer dated to 4-5th century AD, and in that layer you find a pile of ancient books. If you found 1st century books in a 4-5th century layer, that means the books were in use 200 to 300 years ago."

Evans has defended the Green Collection's practices, although he admits he does not know exactly how it dismantles mummy masks and cartonnage, as it is not his field.

He says he is a consultant with the Green Scholars Initiative, which includes many highly respected scholars and archaeologists from around the world.

Evans said: "There are a whole bunch of us. We are on different faculties from different parts of the world and we're just consultants for the Green Scholars.

"The Green Collection has paid staff who work full time in Oklahoma City. They are technicians who know how to handle ancient artefacts, who have archaeological and scientific experience."

Mazza strongly disagrees. She said: "It is not OK to dismantle mummy masks. Some types of mummy masks might resemble each other but we never have duplicates. In that way, we could destroy all copies of manuscripts.

"Why is it that every little fragment is important, but why each mask is not? Who makes that decision? It's not only about destroying, it's about methodology. They are not the first ones to have dismantled mummy cartonnage, but how did they do that, and where did they buy the cartonnage?"

Where are these artefacts coming from?

Like many archaeologists, Mazza is particularly concerned about the private collecting of artefacts, which denies the world's people their heritage by hiding away artefacts that should be displayed publicly for study and enjoyment.

Her key concern is that Christian apologists, who are people seeking to present a rational basis for the Christian faith against objections, have been buying artefacts through unscrupulous means.

And although the Green Collection does not see itself as a Christian apologist association, Mazza believes it is one, and she even presented a paper last year about their practices to the Interdisciplinary Art Crime Conference in Italy.

"In 2012, I was alerted that a papyrus fragment called GC.MS.000462 from the New Testament was being sold on eBay. Then two years later, I went to Rome to visit a Green Collection exhibition and I found the fragment in the exhibition," she said.

"I asked the head of the Green Collection where the fragment came from, and nine months later, the day before I was to give a paper to the Biblical Society of Literature, they replied.

"I was told that the Green Collection bought the papyrus in 2013, and that originally it was part of a collection of papyri bought from Christie's in 2011. They haven't explained how the papyrus went from Christie's to eBay to them."

Why is it taking so long to be published?

IBTimes UK contacted the Green Collection and was told the organisation does not discuss artefacts that have not been published.

Michael Holmes, executive director of the Green Scholars Initiative, said items are published "in the order that they become ready for publication", and it takes time for artefacts to be investigated.

It also does not favour public discussions of artefacts until researchers are able to "make full and carefully considered judgments and to share fully the reasons and evidence upon which those judgments are based".

Mazza thinks the Green Collection needs to become a lot more transparent about its research and methods.

"How on earth is it possible to talk about something we haven't seen? Usually we do announce discoveries before we publish them, I have done the same before with papyrus," she said.

"I have put the image online, I have spoken about it publically at a conference in Manchester, and I have sent the image and research to my colleagues to review. If you are serious, you should not hide it away."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.