Election 2015: We need all-women shortlists to redress the lack of females in politics

To argue for all-women shortlists is a political minefield. Even female politicians pushing to improve female political representation almost unanimously agree all-women shortlists are a "blunt instrument" to shoehorn women into parliament, in theory, to inject some oestrogen into the predominantly male and pale Westminster. But in light of the meagre number of female MPs and the prevailing "Old Boys' Club" attitude to politics, it is the only option we have left.

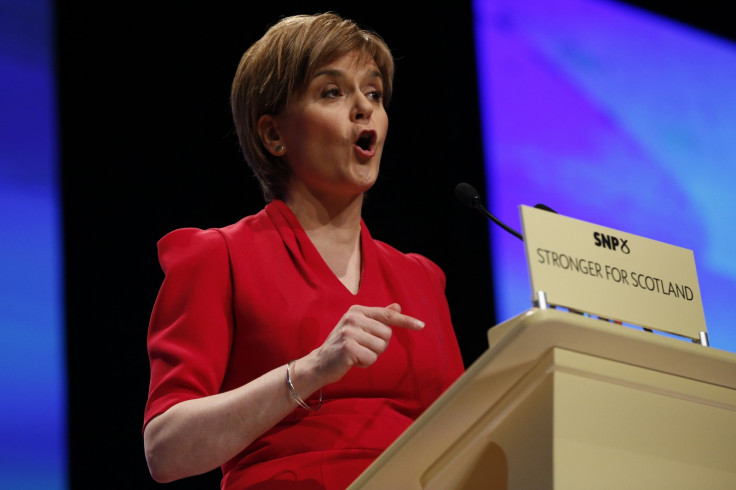

It is the same old arguments against all-women shortlists that crop up time and time again: they are undemocratic, discriminate unfairly against men and elections should be based on meritocracy. There is no denying gender quotas are unpopular. A YouGov poll commissioned by the Times in August 2014 found that 56% of the British public were opposed to all-women shortlists – the majority of whom were men. But at the end of March, the Scottish National Party voted heavily in favour of introducing them, reversing decades-long opposition to positive action.

It is easy to understand why these shortlists rub people up the wrong way. Women would obviously prefer to win without preferential treatment and men do not like being told they cannot put their names in the hat. But the current system is not working: men still outnumber women nearly five to one as MPs. In the absence of any other plan, it is hard to see opposition to temporary positive discrimination – in the form of all-women shortlists – as anything but a preference for the status quo.

All-women shortlists are currently only used by the Labour party, who perhaps coincidentally have the most female MPs of all the parties. In 1992, Labour tried to increase the number of female MPs by requiring at least one women to sit on every shortlist – which stirred up controversy but made very little impact. When all-female shortlists were introduced at the next election, the number of female MPs soared.

Society has not progressed the way it should – which should be the only case against all-women shortlists. But as long as the alternative is a male-dominated Westminster fuelled by sexism, positive action seems a better option. As was the case with the fight for women's suffrage, an organic shift in societal attitudes is idealistic and extremely unlikely – change needs to be enforced.

Women have long been systematically pushed out of parliament by white, well-connected Etonians. Even now, women still face an uphill struggle to get into politics, partly because they are busier - juggling paid employment with caring for children or elderly relatives, but also because the political sphere is still viewed by many as a male domain.

Of the seven leaders who took part in the TV debates on 2 April, three were women – but of the four men they were up against, three had been public schoolboys and three had attended Oxbridge.

Critics are quick to argue all-women shortlists are "undemocratic" – belying the philosophy of meritocracy – but it is difficult to argue about democracy when the last parliament looked so little like the people it was supposed to represent. Since 2000, the number of female MPs has increased by just 4.1%. It is frankly laughable to needlessly endure discrimination against women in politics as a superior option to the "unfair" all-women shortlists - it smacks of Labour MP Austin Mitchell's school of thought; a man who thinks the "feminisation" of his party made the Commons "less exciting".

There has been a gradual realisation that women can do the job of MP as well as – or better than – men, but we can't afford to wait decades for further change. In austere times, when economic decisions have a particular impact on women, it is important their needs and interests are being met. Women are needed in parliament as a matter of social justice and democratic legitimacy: the experiences and perspectives of one half of the country are being ignored.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.