The end of privacy? It's become far too common to shame people on social media

There is no more important place to apply the 'do unto others as you would have them do unto you' principle.

There is ample evidence that when used ethically and while abiding by the sublime 'Do unto others as you would have them do unto you' principle, social media can be a force for good. It allows the forging of friendships, the increase in understanding between different social and ethnic groups, the communication of ideas and so forth.

Social media, however, has the potential to be a means of great harm: the propagation of dangerous lies, the victimisation of the weak, the bullying of the vulnerable, and the humiliation of the disadvantaged. Such is the power and scope of social media that it is impossible for the law to make more than a tiny impact on such behaviour – and even when it does, then the intense conflict between Article 10, the right to free speech and Article 8, the right to privacy, makes this an area in which the law has to tread with great care.

In my last article I wrote about how Paul Gascoigne had been shamed by pictures of him in his diminished state and effectively naked being published by The Sun.

More recently, Playboy model Dani Mathers, whose God-given features are a ticket for her to fame and riches, posted a naked picture of a woman in a shower whose own gifts may well be apparent, but do not include regulation body perfection.

This was not only a gross invasion of this woman's privacy, it was also an act of sororal cruelty and betrayal.

Unsurprisingly, Mathers has now apologised and backtracked by saying that the posting was accidental.

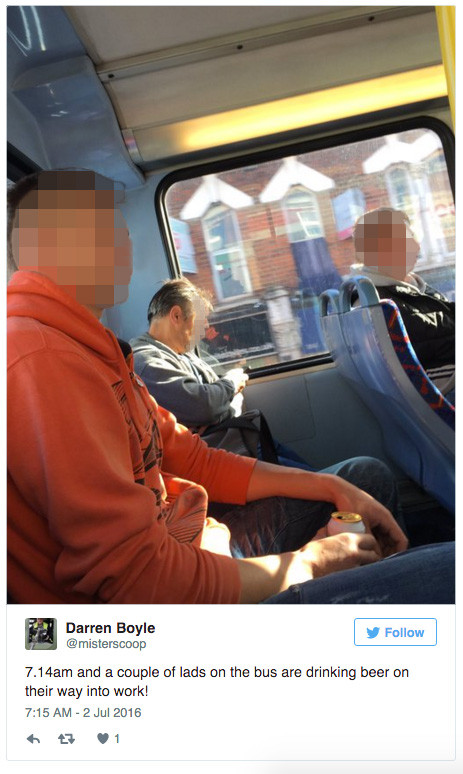

In the past few years, we have seen a plethora of sites pop up with the aim of shaming strangers, for example, Women Who Eat On Tubes or Men Taking Up Too Much Space on the Tube. But more commonly, it's become normal to post pictures of strangers on social media, or indeed private conversations with friends and family – often without their permission.

Did my mum actually just text me asking for weed pic.twitter.com/JzTJBPR0m3

— princess pri ✨ (@priyankanagpal_) 16 July 2016

That moment when Kanye West secretly records your phone call, then Kim posts it on the Internet. pic.twitter.com/4GJqdyykQu

— Taylor Swift (@taylorswift13) 18 July 2016

The desire to post 'selfies' on Facebook, Instagram and other sites appears to be driven by a combination of a desire for identity, significance and narcissism. However it creates a real risk of remorse in the future, when the identity to which we aspired when we were busy violating our own privacy via social media has changed and matured. For those who emerge into the ever expanding galaxy of celebrities, such self-exposure via social media may be a source of intense regret.

Such activity is of considerable significance legally because neither the courts nor the press regulator IPSO will ignore past self-disclosures if their assistance is sought for the purposes of privacy protection. The IPSO Code, which purports to protect the privacy of individuals at paragraph two says: "It is unacceptable to photograph individuals without their consent, in public or private places where there is a reasonable expectation of privacy".

The code also warns that; "account be taken of the complainants own public disclosures of information". As Piers Morgan famously quipped in the seminal Naomi Campbell privacy trial in an attempt to justify the wrongdoing of his newspaper: "Naomi Campbell has been invading her own privacy for years".

For those who emerge into the ever expanding galaxy of celebrities, such self-exposure via social media may be a source of intense regret

As I have explained earlier, the press takes scant note of its obligations under the IPSO Code, and IPSO's administration of its own Code betrays its utter premise and resonant determination to favour the interests of its funder/creator over various of the individuals which any genuine independent press regulator should prioritise.

Dani Mathers taking a picture of another woman in a shower room would be an unlawful breach of the privacy of that woman, as would the posting of that picture on any form of social media. However, the wronged woman's rights are of no practical value because the damage to both her privacy and dignity have already been done. She would also have to be one of the small number of individuals who had both the resolve and means to enforce their rights through the courts; although no-win-no-fee arrangements sometime solve the 'means' problem, which is presumably why they are so hated by the tabloids.

It comes down then to our own consciences, which we often ignore at our peril. I acted for Tulisa when footage of her engaged in an intimate act with her then-boyfriend was posted online a few years ago. That was a gross invasion of her privacy by her boyfriend and the Dickensian cabal of villains who sought to make money out of shaming a beautiful and successful young woman. Thankfully I was able to ensure that these were actions that they came to regret, although I do not know whether at any stage their consciences were engaged.

I believe that we are given consciences as a gift both to protect ourselves and others from harm, and that there is no more important place than social media to apply the 'Do unto others...' principle. Examples such as Dani Mathers' Snapchat will hopefully remind her – and all of us – that we owe a responsibility to the people around us to consider what the impact will be of our actions on others, and not just ourselves.

Jonathan Coad is a specialist media lawyer and partner at Lewis Silkin LLP. He acts for both claimants and defendants.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.