Eternal sunshine of the spotless mind: How PTSD patients can erase unpleasant memories

Changing the way we think about the context of past experiences could make them fade away.

We can intentionally erase memories we do not want to keep, scientists claim. Changing the way we think about the context of past experiences could make them fade away, because context plays an important role in shaping memories, both good and bad. And this could help people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), scientists say.

The study, published in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, examines the changes that happen inside the brain when people are asked to randomly remember or forget a number of words.

It shows that to succeed in both memorising and forgetting, people have to manipulate the context in which they first heard the words.

Scanning the brain for clues

It is well accepted among scientists that context is crucial for individuals to organise and retrieve memories. Situations, smells, sights, places and people around us help us create memories of specific moments, and to get access to them whenever we need to.

The study's authors, from Princetown and Dartmouth universities, wanted to find out whether people could also intentionally forget past experiences, and if so, how this process unfolds in the brain.

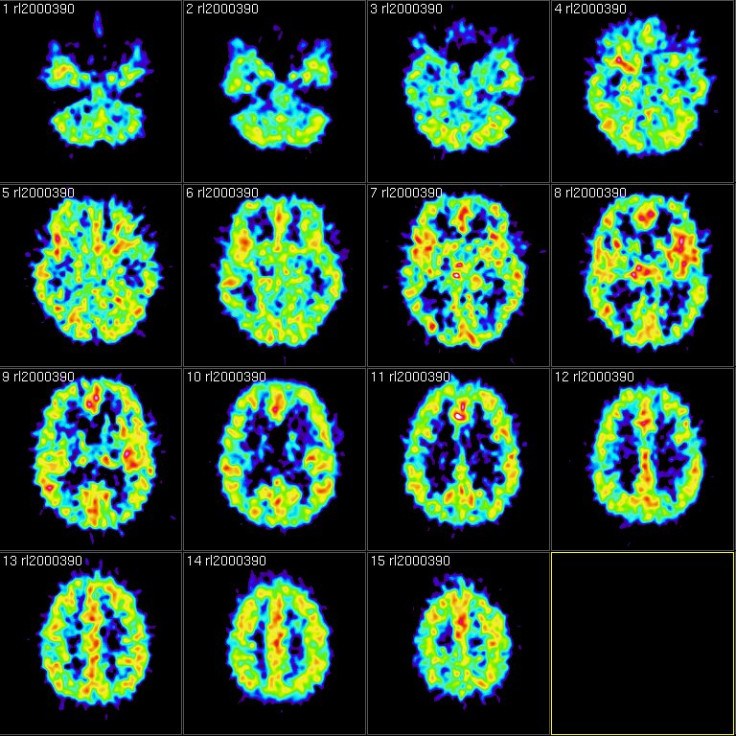

Their research is based on a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Participants studied random words on a list while being shown images of landscapes of beaches, forests or mountains. These outdoors scenes were meant to provide a context within which the words would be memorised.

The participants were then told to remember or to forget some words as the scientists scanned their brains. On the scans, the researchers discovered that when people were told to forget, brain activity relating to remembering the contextual landscape disappeared. Conversely, when they were told to remember a specific word, this particular brain activity remained.

"We used fMRI to track how much people were thinking of scene-related things at each moment during our experiment. That allowed us to track, on a moment-by-moment basis, how those scenes or context representations faded in and out of people's thoughts over time" explains lead-author Jeremy Manning.

The findings suggest that manipulating the way we remember the context of a memory – as well as not thinking about contextual elements associated to this memory – can make it fade away. "It's like intentionally pushing thoughts of your grandmother's cooking out of your mind if you don't want to think about your grandmother at that moment," Manning says.

Future implications

The most important consequence of this study is that it can help people who have gone through a trauma, and suffer from PTSD.

"Memory studies are often concerned with how we remember rather than how we forget, and forgetting is typically viewed as a 'failure' in some sense, but sometimes forgetting can be beneficial, too," Manning concludes.

"We might want to forget a traumatic event, such as soldiers with PTSD. Or we might want to get old information 'out of our head,' so we can focus on learning new material. Our study identified one mechanism that supports these processes."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.