EU referendum: The NHS needs immigration

Announcing her decision to defect from Vote Leave to the Remain campaign, Conservative MP Dr Sarah Wollaston claimed: "If you meet a migrant in the NHS, they are more likely to be treating you than [be] ahead of you in the queue". How right she is.

Migrants fall into two groups: those who are visiting temporarily, and those who are residents. People from the first group who use the NHS have been dubbed 'medical tourists', taking advantage of free healthcare. But such visitors now have to pay for the care they receive.

Visa and immigration applicants from outside the European Economic Area have to pay an annual 'health surcharge' if they plan to stay in the country for more than six months. Those staying less than six months have to pay 150% of the cost of hospital care. EU visitors have to show their European Health Insurance Cards when using the NHS so that their home countries can be billed for their care. These arrangements mean that visitors are no more a drain on the NHS than they are on restaurants or West End theatres: they're paying for the services they receive.

Migrants that become 'ordinarily resident' in the UK are entitled to use the NHS on the same terms as people born here – but they are less likely than the native population to do so. People who migrate tend to be younger and healthier than native populations. Older people and those with disabilities and severe illness are less likely to move, apart from in extreme circumstances. This underpins a longstanding epidemiological phenomenon called the 'healthy migrant effect'.

This is backed up by evidence from NHS data. A University of Oxford study using local authority immigration data and NHS hospital data found that areas with more immigration had lower waiting times for outpatient referrals. On average, a 10% increase in the share of migrants living in a local authority reduced waiting times by nine days. The authors find no evidence that immigration affects waiting times in A&E and in elective care.

Migrants are less likely to be ill, and also more likely to be working. The Institute for Public Policy Research recently reported that EU migrants have higher employment rates than UK nationals. The employment rate of UK nationals is 74%, slightly below the 75% for migrants from EU15 countries (those in the EU before 2004). Employment rates for migrants from newer member states is 83 per cent, although they tend to be in lower-skilled and lower-paid work.

If migrants are working, they'll be paying income tax and making national insurance contributions. These are the sources of NHS funding. This means that resident migrants are likely to be paying their share towards the costs of the NHS.

So immigrants to the UK are more likely to be healthy and more likely to be working. The opposite may be the case for emigrants from the UK. Around 1.2m Britons live in other EU countries – mainly in Spain, Ireland, France and Germany. While some of these emigrants have moved to work, many have chosen to retire overseas. And retirees are more likely to make use of the health system, simply because they are older. On balance, then, the UK benefits from 'healthy immigrants' while exporting 'unhealthy emigrants' for other health systems to deal with.

Are you likely to be treated by a migrant?

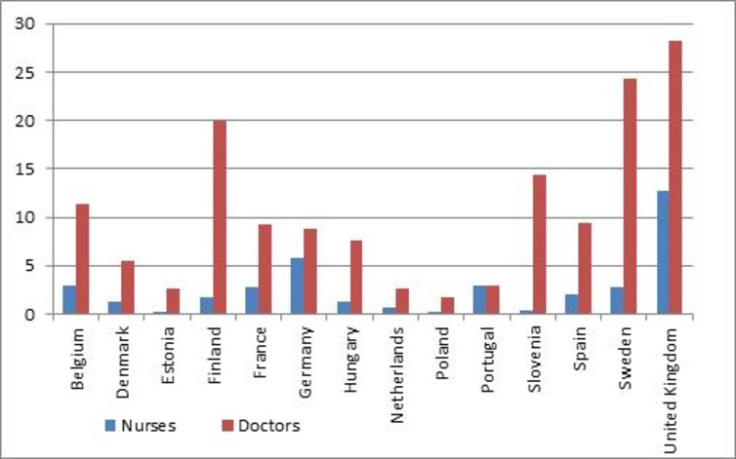

Not only are migrants more likely to working, they are very likely to be working in the NHS. According to statistics collected by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the NHS is more reliant on 'foreign trained' staff than are other EU countries (see chart below).

In 2014, 28% of doctors working in the UK were trained abroad compared with an average of just 9% across the other countries. Thirteen percent of nurses are foreign trained compared with 2% elsewhere. Some of these are trained outside the EU, but 11% of doctors and 4% of nurses working in the NHS are from other European Economic Area countries (the EU plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway).

The Public Accounts Committee has been very critical of evident failures in NHS workforce planning. This has meant that overseas recruitment has been essential to fill shortfalls in staffing. Leaving the EU will make the situation worse, particularly in shortage specialities such as emergency care and general practice, severely constraining our ability to recruit overseas staff.

The Leave campaign claims that Brexit would allow us greater border control, above and beyond the higher entry barriers the UK already has by not being part of the Schengen area. These restrictions are likely to reduce immigration from other EU countries, which may reduce use of the NHS, but would also reduce NHS income received directly from such users or via taxation.

More worryingly, Brexit would reduce access to a pool of staff that we need to draw from in order to address NHS workforce shortages. There also may be adverse consequences for UK emigrants and holidaymakers, if the other EU countries retaliate by making it more difficult to retire abroad or ask us to surrender our European Health Insurance Cards.

Karen Bloor, Professor of Health Economics and Policy, University of York and Andrew Street

Andrew Street, Professor, Centre for Health Economics, University of York

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.