Job losses, bailouts and fines have made for a restless summer in the European banking industry

Negative interest rates and tough regulatory rules are putting banks under pressure across Europe.

It has been a long hot summer for Europe's banking industry. Negative and ultra-low interest rates combined with tougher regulatory rules have rocked some of the continent's strongest banks.

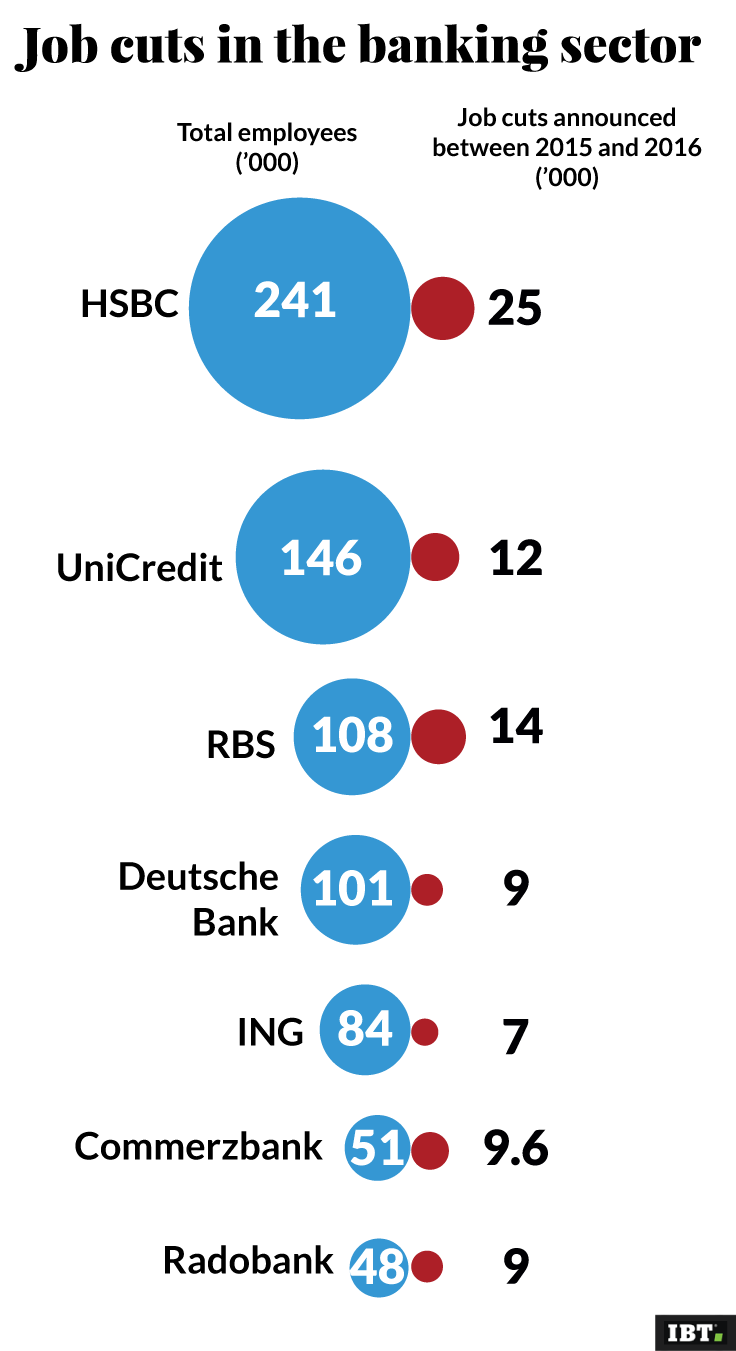

Dutch banking giant ING said on Monday (3 October) it will slash 7,000 jobs as it becomes the latest lender caught in the struggle to make profits amid Europe's tough banking environment.

It announced it would cut more than 13% of its worldwide workforce over the next five years as the bank focuses on investing €800m (£697m, $898m) in new technology and digital platforms.

Germany's biggest lender Deutsche Bank sank to fresh 30-year lows last week, after the US Department of Justice (DoJ) proposed it pay a $14bn penalty to settle allegations of mis-selling mortgage securities in the run up to the financial crisis in 2008.

Pressure on the bank's shares eased this week amid reports that it was close to a deal with the DoJ to pay $5.4bn settlement. Nevertheless, the bank, led by Yorkshireman John Cryan, has previously announced plans to cut more than 9,000 jobs.

Royal Bank of Scotland has seen its stock slide over the last two weeks, as it awaits a settlement with the DoJ on its sale of mortgage-backed securities in the run up to the global financial crisis later this year.

Germany's second largest lender Commerzbank also said last week it would axe 9,600 jobs and suspend dividend payouts "for the time being" due to low interest rates and weak client demand.

Since June the Italian government has been working out how to bailout its entire banking system, without falling foul of European Union state aid rules.

Italy's banks are also in deep trouble, burdened by some €360bn of souring loans, the equivalent of a fifth of the country's gross domestic product. Collectively they have provisioned for only 45% of that amount.

The biggest immediate worry is Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the world's oldest bank, which is trying to put together a €5bn to rescue package. But across the board shares in Italian banks have fallen by about half compared to a year ago.

Banks 'not really investable'

It is little wonder that Credit Suisse chief executive Tidjane Thiam said earlier this month at a Bloomberg conference in London that European banks are in a "very fragile situation" and are "not really investable as a sector".

He added: "I think there is also a lot of doubt, a fundamental doubt, is there a viable business model that covers its cost of equity? That's the big, big, big question."

European banks are battling against a number of headwinds, any one of which could capsize significant parts of the industry. The landscape is the worse the industry has seen since the eurozone sovereign debt crisis in 2009.

The first factor is that it is very difficult to make money out of banking amid zero interest rates, which also frustrates attempts to rebuild capital buffers after the bad debt write-downs of recent years.

Second, comes increasingly tough international capital requirements, measures brought in after the 2008 financial crisis to ensure banks hold more than three times the amount of capital they did previously. This means banks should be less prone to sudden collapse and taxpayer bailout, but also means lenders have less money to hand out as money-making loans.

Third, is the continuing story of misconduct fines, of which the DoJ's claims against the Deutsche Bank is the latest in a long line.

US regulators have the ability to levy the biggest settlements because they hold the power to withdraw key US banking licences, without which no serious bank can to business for international clients.

Bankers complain that negative interest rates imposed by the European Central Bank (ECB) are to blame for their firm's weak profitability.

Too many banks

But earlier this month ECB president Mario Draghi said at a Frankfurt conference that overcapacity among Europe's 7,000 banks was the real problem. He said the banking sector had "outgrown capital markets" and said the high number of European banks was a big factor on the low levels of profitability in the sector.

He added: "Overcapacity in some national banking sectors, and the ensuing intensity of competition, exacerbates this squeeze on margins."

This has long been a key criticism of European banking, that governments for a range of reasons have been kept afloat all manner of banks, whether they are systemically important or not.

This had led to hundreds of so-called zombie banks on life support, limping along supporting thousands of zombie companies, unable to write off the debts of weak and listless firms.

When the ECB president suggests it is time Europe pulled the plug on these banks, you know things are serious.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.