First Christians in the Americas discussed religious beliefs with indigenous people

16th-century markings found in Caribbean island cave show intercultural and religious dynamics.

Cave art recently discovered on the island of Mona in the Puerto Rican archipelago sheds light on the intercultural and religious dynamics that took place between local populations and European settlers during the early colonisation of the Americas in the 1600s.

Mona's caves include the most diverse preserved indigenous iconography in the Caribbean, with thousands of motifs and drawings found. This has allowed archaeologists to gain new insights into the culture that Europeans encountered in their expeditions to the New World in 16th century.

Mona, situated on a key Atlantic route from Europe to the Americas, was at the heart of Spanish colonisation at the time, with Christopher Columbus stopping there during his second voyage in 1494.

Exploration of 'Cave 18' – one of 200 caves on the island – has revealed that the local population was exposed to European culture, but also explained their own beliefs to the newly arrived settlers. Throughout the 16th century, new cultural and religious identities were forged from these exchanges.

As the research team explains in a paper, published in the journal Antiquity, markings on the walls of the cave bear witness to this process and show that both communities were communicating, and even telling each other about their belief systems.

Early evidence of encounters

Out of the 200 caves on Mona, around 60 to 70 have been explored so far. However, Cave 18 is the only one that appears to have been visited by Europeans in the 16th century.

"This is some of the earliest evidence of Christianity in the Americas and how the indigenous Taíno population experienced it. It shows that locals and Europeans interacted and communicated about their beliefs. It is also a very good insight into the origins of the identities that were shaped in the Americas after the European arrival, it shows the process by which hybrid identities were being built", author Jago Cooper of the British Museum told IBTimes UK.

His co-lead author, Alice Samson, from Leicester University, added: "Accounts of the encounters between Europeans and indigenous populations that we have access to are usually one-sided, we often only have the perspective of Europeans. Here, we have evidence of more personal, intimate cultural and religious encounters".

Thirty Christian names and symbols

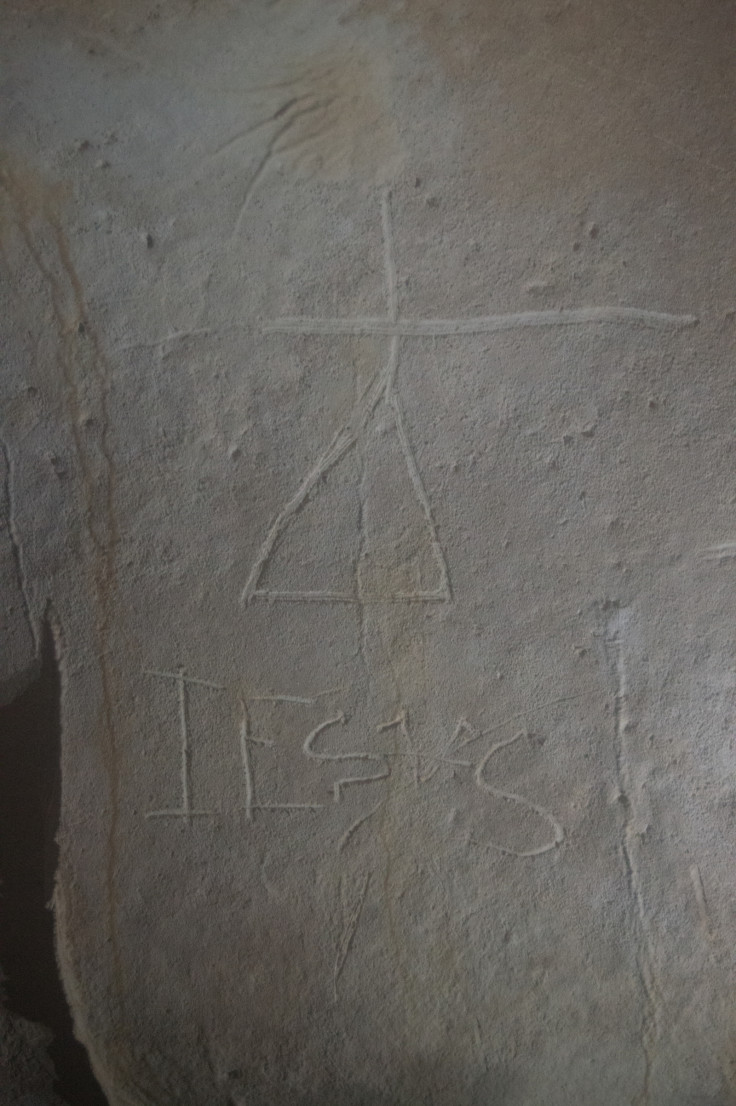

The researchers discovered around 30 historic inscriptions made by Europeans in Cave 18, including names of individuals, phrases in Latin and Spanish, dates, and Christian symbols such as crosses or abbreviations of the name of the Christ. But before the arrival of the Europeans and the marking of Christian symbols, indigenous iconography had already been finger-marked all over the walls of the cave.

"Their iconography is very rich and represents often complex figures, with human and animal hybrids, crosses – distinct from the Christian crosses – faces, and a lot of meandering lines which they made with their fingers", Samson said. In contrast, Europeans made their drawings with tools, probably with daggers and other sharp metal objects.

"What we see is a real communication between both worlds. The indigenous population invited the Europeans into this cave – a very sacred place for them, as they believed that their people had originated from a cave – and told them about what they believed in. In return, Europeans drew their own Christian belief system on the walls", Cooper said.

This impressive account of intercultural religious dynamics brings introduces new perspectives on the interactions between the Old and the New World. Since this cave is the only one found so far on Mona that indigenous people appeared to have brought the Europeans to, future research will focus on why this cave was so special to them.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.