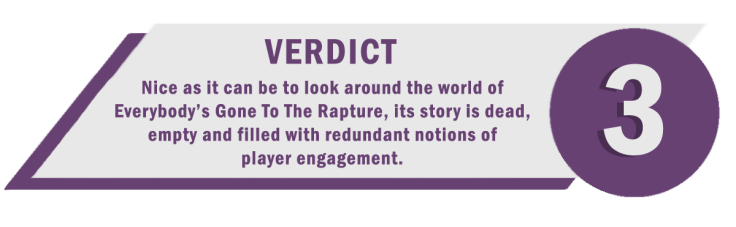

Everybody's Gone To The Rapture review: Boring video game narrative survives the apocalypse

Everybody's Gone To The Rapture

Platform: PS4

Developer: The Chinese Room

Release date: Out now

Price: £15.99

"Look for the answers in the light." As soon as I heard those words in Everybody's Gone To The Rapture's opening monologue, I knew what the game was: fluffy, empty, pseudo-art. Another example of video game developers serving up sizzle and calling it steak. You wander a deserted Shropshire village in the wake of a mysterious apocalyptic event and by following floating balls of light, watch ethereal reconstructions of conversations between the former villagers.

By doing this, you piece together the story of what happened here and to whom. Especially if, like myself, you were born there, there's an inherent novelty to exploring the West Midlands in a video game. But location aside, Everybody's Gone to the Rapture is rote and ornate, the kind of lifeless narrative that for years has been smuggled through customs under the ill-defined rubric of interactive storytelling.

I hate the gaming industry's short memory, its disloyalty to games more than 10 years old – I hate the capriciousness with which history is abandoned, especially when a new console arrives. But every single idea, discipline or – if we must continue to misuse the word, "philosophy" – behind Everybody's Gone To The Rapture has been done, and done, and done again. If anything about games needs to be left behind, after-the-fact narrative told via voice memos (or some equivalent) is it.

Navigating empty worlds, listening to the diaries or spirits or "lights" of people that used to be there is so flaccid and jejune. It's like examining a model, or pressing a button next to a waxwork of Abraham Lincoln, and hearing a recording of the Gettysburg Address. It doesn't matter how much the balls of light in Everybody's Gone To The Rapture argue and fight and swear at each other – they aren't people. They aren't even representations of people. They're just vaguely animated voice recordings.

You could argue that every character, in every game, by virtue of being a 2D or 3D render, is the same, a waxwork more human in appearance but a waxwork nonetheless. To an extent that's true, but there's something about eyes, ears, a face, that make an animated character easier to relate to. This is not the story of a group of people and the place they lived – it's a scavenger hunt for audio files. I feel more for the soldiers alongside me in Call Of Duty than the balls of light in this.

The balls of light ruin Everybody's Gone To The Rapture. It's not because their dialogue is strained, or they implicitly come over as insouciant and simplistically optimistic (everybody is a ball of light on the inside!) It's because you have to look for them. In Dear Esther, The Chinese Room's previous game, you're fed story, directly, as you walk – cross an invisible line and the narrator will start to speak. That leaves you free to just stroll through the game and imbibe the scenery. Even if you don't listen to or care for the game's writing, you can't help but relax and reflect. Like a walk in the country, Dear Esther is something for your eyes to merely enjoy while your mind works.

Everybody's Gone To The Rapture, by contrast, encourages you to walk back and forth; to search, hunt and find. Nuanced as it may be, it's difficult to submerge yourself in the game's environment, since you're always on the lookout for the next guiding orb. It's hard to just be in Everybody's Gone To The Rapture. The implied mystery of the village and the way you're breadcrumbed from place to place make walking feel like work.

The story itself reminds me of a presentation I saw back in 2013, when Sony was announcing the PlayStation 4 and its line-up of launch games. Nate Fox, one of the designers on InFamous: Second Son, walked on stage and started talking about bureaucracy, surveillance culture and governmental control.

"Two years ago, American travellers spent a combined 75,000 hours waiting at airport security," Fox explained. "Our security comes at a high price... our freedom. Now picture how things would change if a handful of people suddenly developed superhuman abilities." It was a gear change so clunky and massive it could be seen from space and it illustrated a prevalent trend in video game writing, of taking ostensible mature subject matter and trivialising it.

Everybody's Gone To The Rapture shows the people of an English village falling in love, making friends, striving to keep their lives and their families together. It borders on a soap opera or maybe, if you're generous, a Capote short story. And then they all vanish mysteriously. I don't know what it is about games that makes writers inject these daffy, science-fiction conceits, but it's a shame. It's a shame video games are so rooted in adolescence that an interesting premise is always rendered boring by so-called entertaining fantasy.

There are a lot of gaps in the game's story and you're encouraged to fill them in using your imagination. It's an approach that seems loyal to the core nature of interaction, insofar as it makes the player an active part of the narrative, but it's a cop-out. Rapture is a dead place full of non-people talking about things that have already happened – no amount of imagination can inject life into that story. And falling back to "it's an experiment", or "for the player to decide", or any other critical Alamo simply won't do. These are exhausted ideas of game design, re-heated and re-sold since BioShock.

In Dead Space, Fallout, Deus Ex: Human Revolution, Gone Home, The Novelist, Her Story, The Talos Principle, Sunset and countless others, relaying narrative through the diaries of characters, found in-game, has been done. We like to complain about AAA and the big video game factories constantly rehashing ideas, but there's a huge catalogue now of independent and apparent sophisticate games all doing the same thing when it comes to narrative style.

Everybody's Gone To The Rapture is just another empty world, masquerading as a story about people. If it has got a point to make about the nature of video games, it's that, increasingly, wherever you go, they're interested in level design more than writing and posturing over substance – the benchmark is still low.

For all the latest video game news follow us on Twitter @IBTGamesUK.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.