Executive pay: Big and getting bigger thanks to the big boys' club

Executive pay rose by 10% last year and neither shareholders nor governments seem able to do a thing about it.

Amid the fragile economies and shaky confidence of the West since the financial crisis, one thing has fearlessly refused to take a backward step – executive pay.

The bosses of the UK's biggest companies took home an average of £5.5m last year, a 10% jump on 12 months ago, according to a report from the High Pay Centre, and a rise of more than a third since 2010.

The median pay of FTSE 100 chief executives rose to just under £4m ($5.22m) last year, 144 times the median wage of the average Briton, which is currently £27,600.

By comparison, for most employees pay rose by around 2% last year, and is only just back to 2008 levels.

These findings come after Theresa May in her leadership pitch to become prime minister last month said: "There is an irrational, unhealthy and growing gap between what these companies pay their workers and what they pay their bosses."

The sense of there being one law for the workers, and another for those at the top of our biggest companies, is hard to shake off.

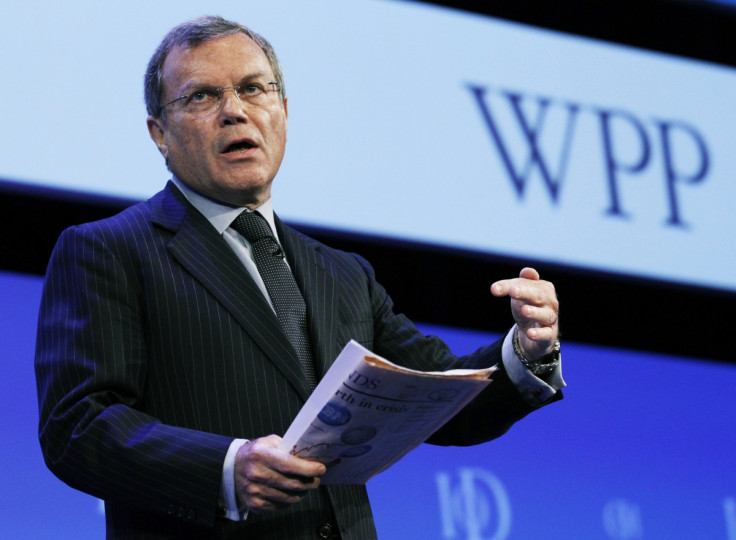

This year WPP advertising boss Sir Martin Sorrell was the UK's highest-paid executive, with £70m, reflecting, his firm said, the performance of shares in the worldwide group he founded.

BP investors rejected a pay package of almost £14m for chief executive Bob Dudley at the oil company's annual general meeting in April, while Smith & Nephew and Reckitt Benckiser faced similar, albeit smaller, rebellions. But these votes by shareholders are advisory, not binding on the firms they hold stakes in.

Large firms blame globalisation for these large rewards. The argument goes that in a worldwide market it simply costs more to attract and keep the brightest talent around the world.

But the counter argument is that multinational firms act as a big boys' club, passing round high awards among themselves.

Around 46% of the people who sit on the remuneration committees of FTSE 100 companies are current or former top executives.

It is too easy to blame globalisation for these rises. It is too easy to say I am an exceptional individual

Even the investment and pension funds, who are tasked with holding these firms to account, say that chief executive pay, when judged against multinational profits measured in billions, is often seen as little more than a rounding error.

High Pay Centre director Stefan Stern told IB Times UK: "It is too easy to blame globalisation for these rises. It is too easy to say I am an exceptional individual.

"The truth is that there is very little opposition in the system. Everyone involved in it is used to seeing very big figures awarded to individuals."

Oliver Parry, head of corporate governance at the Institute of Directors, told IBTimes UK: "The most important thing about executive pay is that it should be aligned to performance. And to help this pay should be less complex."

He said typically the packages of top bosses are split into basic pay, long-term incentives, pension rights, allowances and a number of other awards.

"These are complex, and are sometimes constructed so that only a remuneration expert could understand the formulas used," said Parry.

Parry notes that the value of the FTSE 100 Index is around where it was a decade ago, even though the pay of blue chip executives is "significantly" higher.

But Stern calls for more radical action. He wants workers to sit on board – a Labour policy recently echoed by May – which might have the effect of "grounding discussions about pay".

He would also like to see binding votes on pay by shareholders, and firms being forced to publish the pay ratios of top executives compared to average staff salaries.

However, the role of government in executive pay is always at the mercy of unintended consequences. When the European Union tried to limit bonuses of bank chief executives a few years ago, the result was that the basic pay of heads shot up.

Even so Stern hopes that May, having made a point of addressing the issue in words, intends to attack it with action.

However, executive pay has been growing like topsy for more than 20 years, and it will take sharp shears and steely determination to cut it back.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.