Margaret Thatcher Falkland Files: A Knife in the Heart of the Iron Lady

She called it, simply, the worst moment of her life.

It came in March 1982 during the days before the Falklands War, after Argentina established an unauthorized presence on Britain's South Georgia island amid talk of a possible invasion of the Falklands, long held by Britain.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher realized there was little that Britain could do immediately to establish firm control of the contested islands, and feared Britain would be seen as a paper tiger that could no longer defend even its diminished empire. She was told that Britain might not be able to take the islands back, even if she took the risky decision to send a substantial armada to the frigid South Atlantic.

"You can imagine that turned a knife in my heart," Thatcher told an inquiry board in postwar testimony that has been kept secret until its release by the National Archives on Friday, 30 years after the events it chronicles.

"No one could tell me whether we could re-take the Falklands - no one," she told the inquiry board. "We did not know - we did not know."

The assessment is more downbeat than the view offered in Thatcher's memoir, The Downing Street Years.

Thatcher's handling of the Falklands crisis is remembered as one of the key tests of her leadership. The former prime minister, now 87, has been hospitalized since having a growth removed from her gall bladder shortly before Christmas. She has stayed out of the public eye in recent years because of worsening health problems.

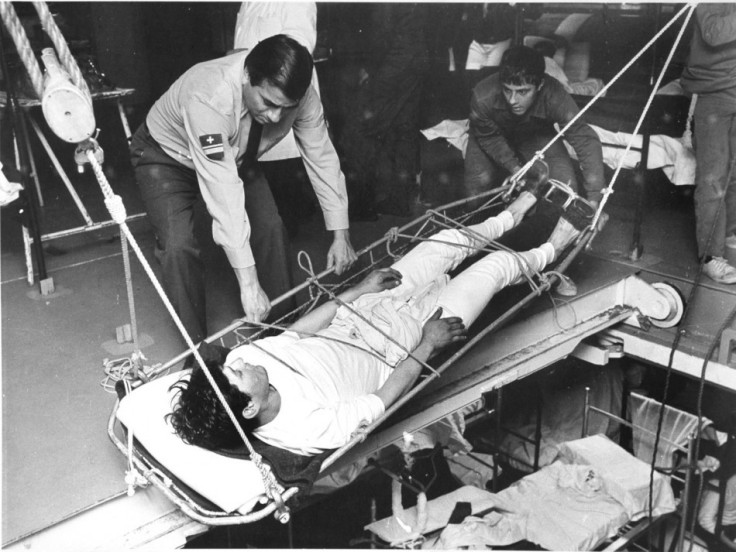

Argentina did invade on April 2, and Thatcher launched a naval task force to take back the islands three days later, after the United Nations condemned the invasion. Britain succeeded by mid-June. The war claimed the lives of 649 Argentines and 255 British soldiers, along with three elderly islanders.

Thatcher testified she had been terrified that by sending the seaborne force which would take weeks to reach the Falklands (known as Las Malvinas in Spanish) she would provoke even more aggressive action by the Argentines while the vessels were in transit. She feared this might make the military operation even more hazardous when they arrived.

She persisted in the bold mission despite the risk of an Argentine troop buildup that might force her to turn the armada back, a result that she said "would have been the greatest humiliation for Britain."

She doesn't state the obvious political cost: The mission's failure would have cut short the career of Britain's first female prime minister with her almost inevitable sacking as party leader.

Britain was Unprepared for Invasion

The vivid picture of Thatcher's feelings of helplessness and rage - and eventual resolve - are portrayed in thousands of pages of formerly Secret documents released by the National Archives.

Historian Chris Collins of the Thatcher Foundation - which plans to make the documents available online - said Thatcher's testimony before the inquiry chaired by Oliver Franks was "very carefully prepared" because she felt politically vulnerable.

"She was concerned at the damage the report might do her, because there was much potential for embarrassment at the government's pre-war policy of trying to negotiate a settlement with Argentina ceding sovereignty while leasing back the islands for a period, plus suggestions that Argentine intentions could have been predicted and invasion prevented," he said.

She concedes to the committee that her political analysis was incorrect because she believed Argentina's junta would not invade, as it was making progress at the United Nations in its effort to build diplomatic support for its claim to the disputed islands. She said she thought the junta wouldn't risk this support with unilateral military action.

"I never, never expected the Argentines to invade the Falklands head-on," she told the inquiry board, which was investigating, among other things, whether the government should have been better prepared. "It was such a stupid thing to do, as events happened, such a stupid thing even to contemplate doing. They were doing well."

The papers detail how Thatcher urgently sought U.S. President Ronald Reagan's support when Argentina's intentions became clear, and reveal Thatcher's exasperation with Reagan when he suggested that Britain negotiate rather than demand total Argentinian withdrawal.

Iron Lady Mode

The documents describe an unusual late night phone call from Reagan to Thatcher on May 31, 1982 - while British forces were beginning the battle for control of the Falklands capital - in which the president pressed the prime minister to consider putting the islands in the hands of international peacekeepers rather than press for a total Argentinian surrender.

Reagan's considerable personal charm failed on this occasion. Thatcher, in full "Iron Lady" mode, told the president she was sure he would take the same dim view of international mediation if Alaska had been taken by a foe.

"The Prime Minister stressed that Britain had not lost precious lives in battle and sent an enormous Task Force to hand over the Queen's Islands (the Falklands) immediately to a contact group," says the memo produced the next morning by Thatcher's private secretary. She told the president there was "no alternative" to surrender and re-establishment of full British control.

The newly public documents also reveal an extraordinary draft telegram written several days later by Thatcher to Argentinian leader Gen. Leopoldo Galtieri in which she describes in very personal terms the death and destruction both leaders would grapple with in the coming days unless Argentina backed down.

She tells her counterpart that the decisive battle is about to begin, imploring him to begin a full withdrawal to avoid more bloodshed.

"With your military experience you must be in no doubt as to the outcome. In a few days the British flag will once again be flying over Port Stanley. In a few days also your eyes and mine will be reading the casualty lists. On my side, grief will be tempered by the knowledge that these men died for freedom, justice, and the rule of law. And on your side? Only you can answer the question."

The telegram was never sent, and Galtieri resigned in disgrace several days after Britain reclaimed the islands.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.