First ever 3D printed plastic devices that can connect wirelessly to the internet now available

These devices have no batteries or circuits, but can connect to the internet.

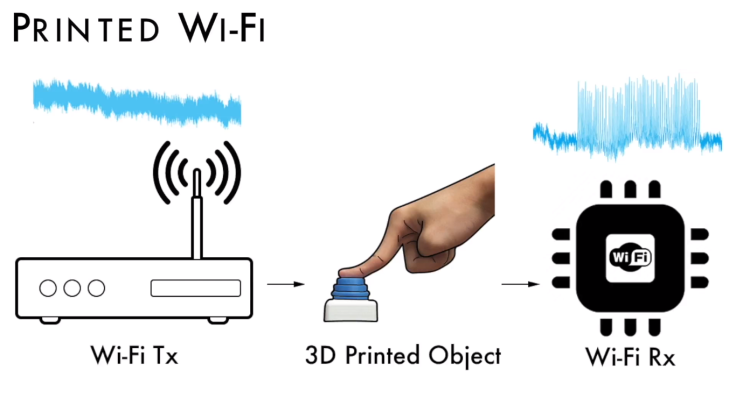

For the first time ever, objects made of plastic materials have been connected to the internet without any electronics and batteries. Called "Printed Wi-Fi", a team of researchers from the University of Washington (UW) have been able to create sensors made entirely of plastic and have it interact with a receiver wirelessly.

These sensors make use of ambient Wi-Fi signals and either absorb or reflect them. The reflection and absorption patterns are read by a receiver – which could be a smartphone – and they register as 0s and 1s, said the team.

"Our goal was to create something that just comes out of your 3D printer at home and can send useful information to other devices," said co-lead author and UW electrical engineering doctoral student Vikram Iyer.

"But the big challenge is how do you communicate wirelessly with Wi-Fi using only plastic? That's something that no one has been able to do before."

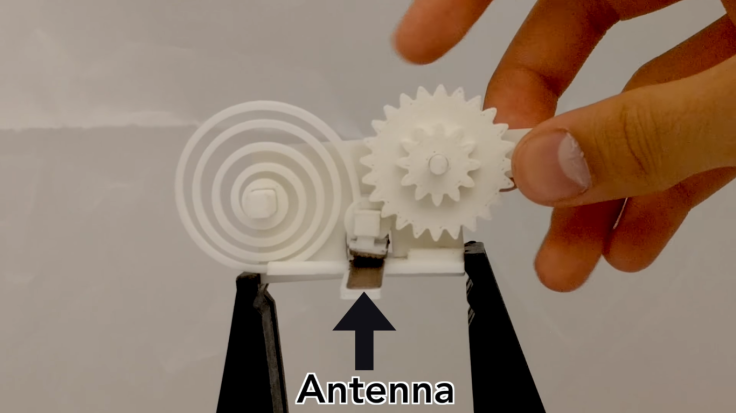

Backscatter – ambient Wi-Fi – techniques were used by researchers and they were able to make these devices communicate with each other. By replacing circuitry with mechanical switches, it becomes possible for objects that do not conduct electricity to still make use of Wi-Fi. A Phys.org report noted that this is a similar method by which analogue automatic watches keep time.

At the core of this system is a switch operated by a gear. The gear works a spring, which in turn operates an antenna. This antenna is printed out of a conductive filament – made out of a mix of plastic and copper – and when the switch makes contact with the spring, Wi-Fi signal transitions are recorded by the receiver. This way, a sensor or a switch or even a knob can be simply 3D printed out of plastic and used.

Every click of the gear against the spring will cause the conductive switch to either engage or disengage, sending out signals to the backscatter receiver. Controls can be programmed into the spring and switch system by alternating the teeth on the clicking gears. Also, the length of each click and the force of switches colliding can be altered based on the size and width of the gears, noted the report.

One of the examples mentioned in the report involved a liquid soap dispenser and a sensor placed at its mouth. When detergent flows out, based on its flow, the level inside the bottle can be decoded based on the speed of the sensor spinning. So when the bottle is running low, a new one can be ordered online, automatically.

Buttons, knobs, sliders and other input devices can be created in this same way, noted the researchers. By using iron in the filament instead of copper, magnetic properties of the material can also be exploited, encoding messages directly into the switch itself.

"It looks like a regular 3D printed object but there's invisible information inside that can be read with your smartphone," said Allen School doctoral student and co-lead author Justin Chan.

The report went on to add that CAD models for 3D printing are available for anyone to download and make use of for free, and commercially available plastics and 3D printers are sufficient to print out these controllers.