The five spectacular fails that helped hackers take down the DNC

From FBI prank calls to a lack of cybersecurity know-how – how did it come to this?

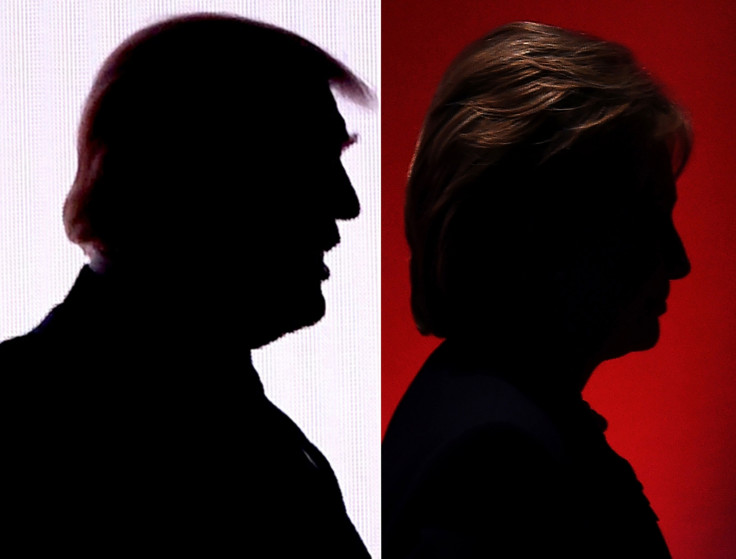

The cyberattack at the Democratic National Committee (DNC) – depending on which US intelligence agency you listen to – was a key stage in an unprecedented Russian influence campaign designed to help get the Republican presidential candidate, Donald Trump, into the White House.

Yet the infiltration did not happen overnight. In reality, it was a lengthy series of blunders that led to the political entity becoming so completely compromised by Kremlin-linked hackers . The new era of warfare had arrived, less bombs and more binary.

From the failure of key DNC officials to recognise glaring security issues, to multiple warnings from the federal government being ignored, the inability to fend off the state-sponsored hackers was never truly the fault of one poor staffer but rather a spectacular case of collective incompetency.

In the latest in-depth analysis of the incident released by the New York Times, the staggering scope of the hack becomes clear. It was a long-game, and the report shows that from the very beginning neither DNC – nor the powerful individuals inside it – were equipped to deal with the threat. But just how did it come to this?

Staff failed to take cybersecurity seriously

According to the NY Times, which based its probe on a series of insightful insider interviews, staffers at the DNC failed to recognise – or take seriously – the damage that hackers can cause an organisation, never mind one that is central to the political system in a major superpower.

When FBI special agent Adrian Hawkins contacted the DNC in September 2015, just under a year before the revelations would be exposed to the world, he spoke about a computer intrusion by a group linked to Russia called "The Dukes" that had previously targeted the White House.

The person who took the call, Yared Tamene, a part-time IT contractor, searched for references of the group online while doing a scan of the DNC's computers for malicious activity. He later admitted failing to respond to further FBI calls because – in his own words – they may have been a prank.

The FBI failed to follow up

When the FBI failed to solicit a response from the DNC (after telling it about the suspected intrusion by a foreign rival government, no less) it then reportedly failed to follow up to officials in person. Agent Hawkins, the Times found, did not visit the DNC headquarters in person.

Shawn Henry, an ex-FBI cyber expert, said: "We are talking about an office that is half a mile from the FBI office that is getting the notification. This is a critical piece of the US infrastructure because it relates to our electoral process, our elected officials, our legislative process, our executive process." By November, the situation had escalated, the computers were "calling home" to Russia.

The politicians failed to recognise phishing attacks

High-level politicians – in fact anyone with access to the internet – should be aware of phishing scams. Cybercriminals can create false links that when clicked will download malware onto a computer – sometimes a keylogger that can later be used to steal login credentials.

In the case of the DNC, the hackers, believed to be with ATP28 (or "Fancy Bear"), used the techniques to exploit a slew of political figures with ease. In one instance, as previously reported, John Podesta fell victim to this and as a result lost nearly 60,000 of his own emails.

"Why use your most sophisticated tool if a very simple one gets you in the door?" Toni Gidwani, a director of research operations at ThreatConnect, told IBTimes UK.

"[Hackers] will use phishing to get in and then start deploying tools that will allow them to get access to other parts of the network. Once that happens, it becomes much more difficult to eject them from the network."

The DNC failed to tell anyone

As the months rolled on, as two suspected Russia-backed groups continued to pillage the DNC's computer networks for sensitive documents, files and dossiers, officials failed to tell the experts who could have helped them kick the hackers from their systems.

In April 2016, months after the problems were first reported by the federal government, the DNC installed a "monitoring tool" which then highlighted what it already knew: it was being exploited from the inside. This person, or collective, it found, had "administrator-level security status."

Only then, the DNC hired Crowdstrike to properly evaluate its systems. Within a day, the Times reported, the problems had been classified as a suspected Russian operation. Even more embarrassing, the experts said two groups had infiltrated the networks independently of each other.

By July, the problems had hit the headlines. After the emergence of Guccifer 2.0, a suspected Russian propaganda front, WikiLeaks disclosed 20,000 emails from the DNC. It denied to discuss how these were obtained, but in any case they led to the resignation of a number of key officials.

In the same month, it emerged the hacking campaign was wider than previously believed – with cybercriminals also targeting the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), a group that handles donations for democrats running for the US House of Representatives.

However, according to the Times, even after DNC officials learned that the DCCC had been infected, they declined to notify their sister organisation, which operates from the same building, because they were "afraid that it would leak." After this, the problems only intensified.

The government failed to attribute the hacks

Unlike some attacks by other nations, specifically China and North Korea, the US government chose not to officially attribute the hacks to Putin's state. The reasons spanned from a fear of escalating the so-called cyberwar to concerns over the military relationship over the crisis in Syria.

Whatever the case, the lack of acknowledgement from the high-echelons of power ensured the Russian hackers had free reign to act – namely, by releasing sensitive documents into the public domain that many now believe were a coordinated attack on democracy in the US.

"We'd have all these circular meetings in which everyone agreed you had to push back at the Russians and push back hard. But it didn't happen," one intelligence source told the Times. When the official briefing was released, it was arguably too-little-too-late.

The dust is yet to settle. President Obama has ordered a "full review" that will analyse the impact the hacks had on the 2016 election. The CIA believes it was a direct attempt by the Kremlin to elect Trump, while other US intelligence chiefs admit clear involvement of nation-state hacking.

The term "cyberwar" remains contentious in cybersecurity circles. While tensions between the US and Russia remains high, the DNC has proven how things have moved on since the Cold War. Forget nuclear war, a team of hackers with some laptops and an internet connection can be just as effective.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.