Five years on, Brexit bedevils pandemic-hit UK

In Britain, at least 5.3 million long-resident Europeans have applied for settlement status to ensure their pre-Brexit rights are preserved.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson on Wednesday extolled Britain's decision to "take back control of our destiny", five years after a divisive Brexit referendum whose political and economic aftershocks are still reverberating.

The coronavirus pandemic has masked the trade dislocation caused by the referendum of June 23, 2016, in which a slim majority voted to end five decades of integration with the European mainland.

The benefits promised by Johnson for a newly invigorated "Global Britain" remain a work in progress, while the UK's own cohesion is at risk from an emboldened nationalist movement in pro-EU Scotland.

But the Conservative prime minister, who rode to power after years of post-referendum political paralysis, remains upbeat.

"Five years ago the British people made the momentous decision to leave the European Union and take back control of our destiny," Johnson said.

"Now as we recover from this pandemic, we will seize the true potential of our regained sovereignty to unite and level up our whole United Kingdom.

"This government got Brexit done and we've already reclaimed our money, laws, borders and waters."

In reality, Britain remains bound by reams of EU-era legislation, its fishermen are in uproar, and its farmers are crying betrayal over new trade deals.

Britons voted by a narrow margin of 52-48 to leave the EU. A new Savanta ComRes poll found that if the referendum were repeated today, the result would be 51-49 in favour of staying in.

But when asked if the UK should now rejoin the EU, 51 percent disagreed.

"I think that whatever happens, whether it's going to be good or it's bad, I think it's better to have our future in our own destiny," 60-year-old musician Stephen Clark said in Boston, eastern England, which recorded Britain's highest pro-Brexit vote in 2016.

But for the majority of Scots who voted to stay in the EU, the question of national destiny rings equally true.

The Scottish National Party is vowing to hold a new referendum on independence by the end of 2023, although the UK government again ruled that out on Wednesday.

"The impact of Brexit hasn't come because we've been too preoccupied, as the rest of the world has, with Covid," pro-independence university lecturer Diane Willis said in Edinburgh.

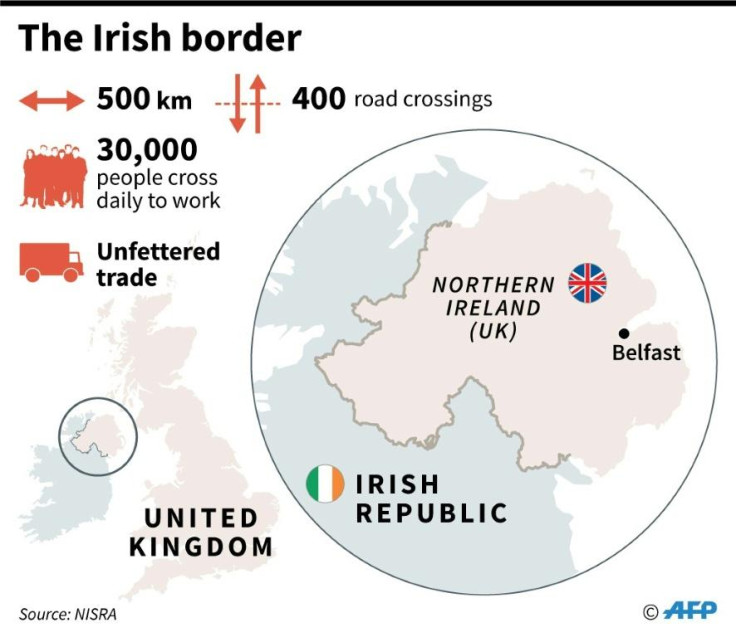

"But I think things are now seeping in," she said, giving Northern Ireland as one example where the scale of post-Brexit complications is becoming clear.

"The devil is always in the detail, and I don't think the detail yet has come out."

Northern Ireland remains in tumult after Brexit necessitated a set of intricate compromises to preserve its fragile peace.

The territory's biggest pro-UK party has shed two leaders in quick succession, and London is trying to rewrite the Brexit treaty's Northern Ireland Protocol in the face of protests and legal action from Brussels.

"The current position of the protocol is not sustainable," Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis told MPs in London, amid an ongoing row over trade in chilled meats dubbed the "sausage war".

The EU's ambassador to London, Joao Vale de Almeida, said the UK could face its own break-up.

"I don't know what our relationship will be in 20 years' time. I don't know what the EU will be like in 20 years. And maybe I don't know what your Union here will be like in 20 years' time," he told The Times newspaper.

"Who knows? So we have to be ready for change."

In Britain, at least 5.3 million long-resident Europeans have applied for settlement status to ensure their pre-Brexit rights are preserved -- well above the government's estimate of 3.4 million.

Any remaining Europeans have until June 30 to apply, threatening new battles with Brussels if some slip through the net and are deemed illegal aliens by London.

Writing in The Telegraph, Home Secretary Priti Patel complained in turn that some British expatriates are having problems accessing benefits, services and jobs in EU states.

King's College London economics professor Jonathan Portes said the immigration patterns experienced when Britain was part of the EU "will have very long-running social, cultural, political consequences long, long after Brexit and free movement are over".

In an online briefing for the anniversary, Portes also said that Britain's economy was suffering a "slow puncture" from Brexit, with a drag on growth of a quarter-to-half percent a year "for the foreseeable future".

Britain and the EU will remain bound by a host of committees envisioned under their last-gasp Trade and Cooperation Agreement signed on December 24.

Copyright AFP. All rights reserved.

This article is copyrighted by International Business Times, the business news leader