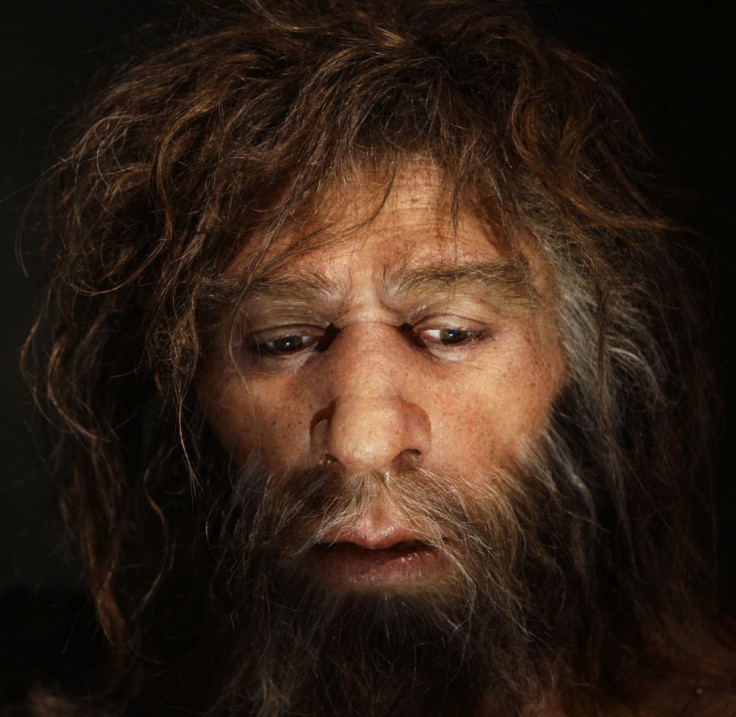

Genetic mutation for fire tolerance may have given us the edge over Neanderthals

Better hydrocarbon receptor made humans up to 1,000 times more desensitised to smoke toxins.

A genetic mutation that made our early human ancestors more tolerant to smoke toxins may have given us the evolutionary edge of Neanderthals. Scientists have found key differences in a receptor involved in the body's response to certain toxins that made humans better able to cope with smoke exposure, meaning they could better harness it for their development.

The ability to control fire considered to be a major step forward in our evolutionary history, allowing human ancestors to expand their diets. There is evidence of hominin species using fire as far back as two million years. Neanderthals are also known to have used fire, with recent research showing they had continuous use of it from around 400,000 years ago through to their demise around 40,000 years ago.

In a study published in the Molecular Biology and Evolution, researchers looked at how different species coped with the toxins from smoke.

They compared the genetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (toxins found in smoke) in humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans (another hominin species more closely related to Neanderthals).

Their findings showed huge differences in how each species was able to process the toxins, with humans being far more desensitised to them.

Study author Gary Perdew, from Penn State University, said: "For Neanderthals, inhaling smoke and eating charcoal-broiled meat, they would be exposed to multiple sources of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are known to be carcinogens and lead to cell death at high concentrations."

At high concentrations, smoke toxins can increase the risk of respiratory infections and among pregnant women, it can increase the risk of infant mortality and a low birth weight. By being able to better metabolise the toxins, human ancestors could have had an advantage of Neanderthals, Perdew said.

"The evolutionary hypothesis is, if Neanderthals were exposed to large amounts of these smoke-derived toxins, it could lead to respiratory problems, decreased reproductive capacity for women and increased susceptibility to respiratory viruses among preadolescents, while humans would exhibit decreased toxicity because they are more slowly metabolising these compounds," he said.

"We thought the differences in aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand sensitivity would be about ten-fold, but when we looked at it closely, the differences turned out to be huge," said Perdew. "Having this mutation made a dramatic difference. It was a hundred-fold to as much of a thousand-fold difference."

As well as potentially playing a role allowing humans to become the dominant hominin species, the team also believes it could have paved the way for habits like smoking: "Our tolerance has allowed us to pick up bad habits," Perdew said.

EMBARGO TUESDAY 2ND AUGUST 22:00

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.