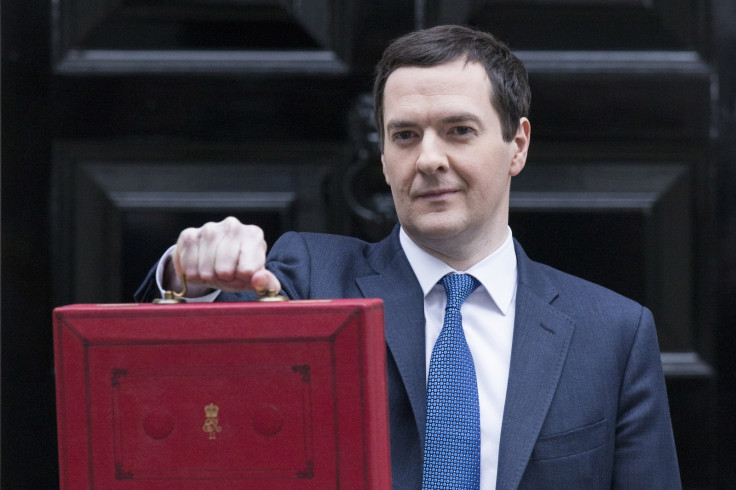

George Osborne election budget: How women have been excluded from economic recovery

Good figures on employment and growth are set to shine through George Osborne's budget speech on 18 March, but they will do little to shroud the alarming picture that the gendered impact of austerity cuts have painted for the economic recovery of women in Britain.

Women have essentially been frozen out of the process: they take home 85p for every pound earned by a man, make up the majority of those in low-paid jobs and around one million women are "missing" from the UK workforce because of a lack of flexible work opportunities necessary to balance work and caring commitments.

Women are losing out die to cuts to public services, being forced from their jobs in the public sector and having their pockets hit hardest due to cuts and freezes of social security

As the chancellor reveals more austerity plans in his final budget speech before the general election, women are set to fare badly. The government intends to impose larger spending cuts than in any other advanced economy - bigger than in any period in post-war history - to lower spending to levels last seen in the 1930s, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Yet the current austerity agenda and programme of deep spending cuts has left women facing a "triple jeopardy" of cuts to jobs, benefits and essential services, locking them into poverty. "Women have fared extremely badly under the government's austerity programme," Polly Trenow, of the Women's Budget Group, tells IBTimes UK.

"They are losing out die to cuts to public services, being forced from their jobs in the public sector and having their pockets hit hardest due to cuts and freezes of social security."

So why have women fared so badly in an age of austerity?

Public sector cuts

Women make up around two-thirds of the public sector workforce, so cuts to this sector are hitting them harder. According to the WBG, there is evidence women are not sufficiently benefiting from government action to create jobs in the private sector.

"Women make up the bulk of public sector employees, so the cuts to public sector jobs have forced many women out of secure employment and into low-waged work," Trenow says. "As many as one in four women now earn below the living wage and this is of particular concern in local government, where women make up 75% of employees."

Local government has faced some of the worst budget cuts of all the government departments. So far, local government cuts have led to a major reduction in the funding of social care – intensifying the pressure on the NHS.

Social security

Women lose more from the direct tax and welfare changes than men, mainly because females receive a larger proportion of benefits and tax credits relating to children – which have comprised a large proportion of the social security cuts between 2010 and 2015. With this heavier reliance on social security, austerity measures disproportionately affect women.

Overall, social security makes up twice as much of women's income than men's, so the freezing and uprating below inflation as part of inflation has hurt women – particularly single parents and lone pensioners – more than men.

"Around 66% of these changes have come from women's pockets," Trenow says. "Female lone parents have lost 16% of their living standards – their cash income plus the value of income in-kind as public services received – since 2010 and female single pensioner have lost 12%."

Employment and pay gap

In his budget speech, Osborne will paint a strong employment picture. The rate of unemployment has fallen sharply – from a peak around 8% to below 6% – and the employment rate has equalled the highest level on record. Still, the economic situation for women is still bleak. The rate of employment for women is at its highest, but it is still 10% below the men's rate.

Also, Trenow points out, it is pertinent to ask what type of work women are going into. "Since 2008, we have seen self-employment increase by 38% for women and 8% for men," she says. "People working part-time 'involuntarily' has almost doubled since January 2008 and women account for 57% of those jobs, as well as 74% of all part-time jobs."

The gender wage gap is at its lowest level since records began, with men earning around 17.5% more than women on average per hour – a decline of around two percentage points in a year. It might be a sign of progress, but there is still some way to go before the gap closes.

"Under austerity we also saw the gender wage gap increase for the first time in many years and now, despite so-called economic recovery in the private sector the gap stands at 26% - higher than the public sector," Trenow says. "It has only has only just started to fall slightly since 2013, from 27%."

Closure of refuges

Services and networks protecting women against domestic violence are under terrible strain as local authorities are facing a tsunami of funding cuts, threatening to send the country into a crisis that could set support for some of the most vulnerable women back by 40 years.

Some houses have been forced to close for good with no offer of alternative accommodation, while others have had their funding slashed because they do not take in men. The Haven Wolverhampton, which has run refuges in the area for 41 years, had its funding cut in 2014 by £300,000. It is struggling to stay afloat and has been forced to reserve some of its places for men – but it has not had a male referral to date.

There also needs to be an urgent review of how services are commissioned. Short-term contracts mean successful services like Refuge's are forced to undergo a constant churn of recommissioning

Sandra Horley CBE, chief executive of domestic violence charity Refuge, says since 2011, the organisation has experienced a reduction in funding across 80% of its service contracts.

"Refuge has increasingly had to rely on donations from the public to plug the gap left by the funding cuts," she says. "There also needs to be an urgent review of how services are commissioned. Short-term contracts mean successful services like Refuge's are forced to undergo a constant churn of recommissioning."

"Not only is this process hugely expensive, but it is also incredibly disruptive for the women and children who access these services," Horley adds. "In some cases the amount of time that women are allowed to stay in a refuge has been drastically reduced to a matter of weeks."

This is simply not enough time, she says before adding: "Women need an average of five to six months' support before they are ready to move on, sometimes longer."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.