Here's why you might not stick to your New Year resolution of exercising more

Inactivity may be a consequence rather than a cause of obesity.

Obese people are often less active, and scientists have discovered that the reason might not just be down to the difficulty of carrying more weight. Defective dopamine signalling may also explain why they are less likely to move.

After the excesses of the Christmas season, many people take the new year resolution to exercise more. However, it is not always easy to stick with sport and dieting, especially after gaining a lot of weight.

It can be particularly difficult for people who are obese, and the consequences can be devastating. Obesity is indeed associated with physical inactivity, which exacerbates the health consequences of weight gain.

What exactly mediates this link between inactivity and obesity remains unclear. Studies have previously suggested that obese humans and animals found that their weight was a barrier to them moving, but few other theories have been proposed.

Senior author Alexxai V Kravitz, from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, said: "We know that physical activity is linked to overall good health, but not much is known about why people or animals with obesity are less active. There's a common belief that obese animals don't move as much because carrying extra body weight is physically disabling. But our findings suggest that assumption doesn't explain the whole story."

In the study published in the journal Cell Metabolism, the scientists have worked with mice, investigating another physiological factor that could be responsible for inactivity – a dysfunction in the animals' dopamine systems.

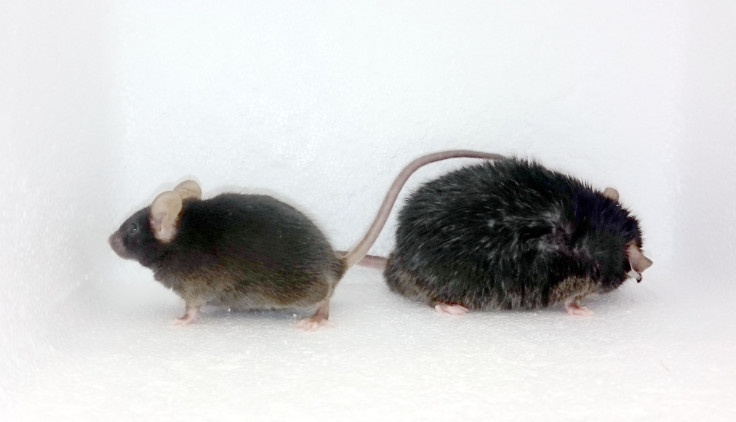

Obese and lean mice

The scientists worked with two groups of mice — lean mice and mice which they had made overweight by feeding them with a high-fat diet for 18 weeks.

By week four, the mice with the unhealthy diet spent less time moving and moved much more slowly than the lean mice.

What was surprising however was that this inactivity appeared even before the mice gained the majority of their weight. This indicates that the extra weight to carry on their bodies was not solely responsible for their inactivity.

The scientists thus decided to take a look at the dopamine signalling pathway in the brains of the mice, because it is linked to movement. "Other studies have connected dopamine signalling defects to obesity, but most of them have looked at reward processing – how animals feel when they eat different foods. We looked at something simpler: dopamine is critical for movement, and obesity is associated with a lack of movement. Can problems with dopamine signalling alone explain the inactivity?" Kravitz explained.

They found that dopamine D2-type receptor binding was reduced in obese mice. Restoring normal signalling increased activity in obese mice. In contrast, genetically removing D2 receptors from neurons was sufficient to reduce motor activity in lean mice.

However, these lean mice were not more likely to gain weight when they started moving less, which suggests that inactivity might be a consequence, more than a cause of obesity.

The study is important because it identifies a possible explanation for why people are less active after gaining a lot of weight or when they are obese. It can reduce the stigma they face by showing they may not be inactive by choice.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.