Historic England: Previously unseen photos provide a fascinating record of 150 years of history

Ever since the invention of photography in 1839, photographers have engaged with the past and the present, recording traces of past societies, as well as capturing the world around them. A new book illustrates 150 years of England's history, providing a fascinating look at the changing appearance of the nation's buildings, landscapes and people.

The book features more than 300 pictures from the archive of Historic England (formerly known as English Heritage). With its nine million images of buildings and landscapes around the country, the archive is a priceless resource for anyone interested in architecture, archaeology, the natural environment and social history.

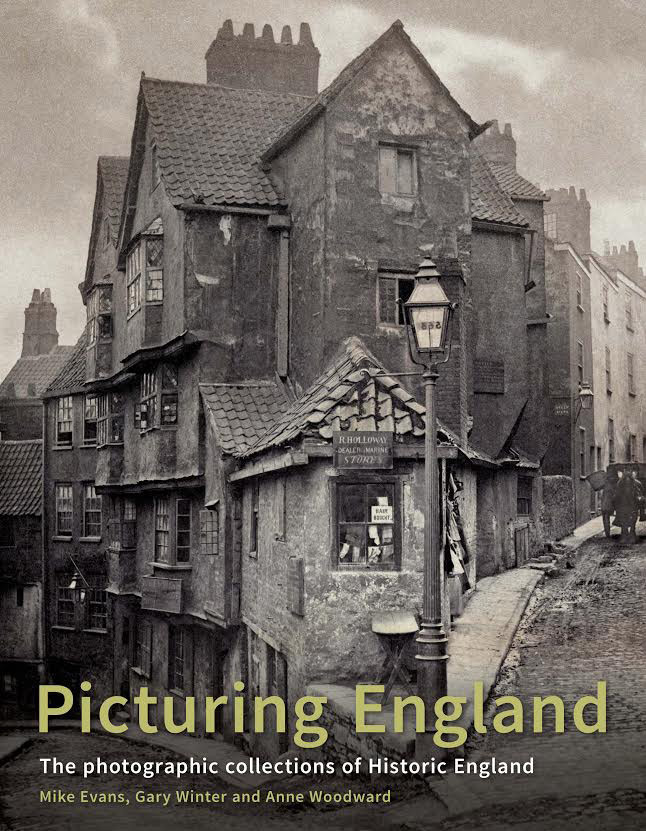

Picturing England pinpoints major turning points in the history of photography, demonstrating how inventions such as the picture postcard, the handheld camera and the aeroplane changed the medium forever. Many of the photos in the book have never been published before.

In this gallery, IBTimesUK presents a selection of images and the stories behind them.

London's city skyline is under constant flux, with towers being demolished and replaced by even taller towers. But one architectural masterpiece remains constant: St Paul's Cathedral, built between 1675 and 1710 after the destruction of its predecessor in the Great Fire of London.

This view of St Paul's Cathedral looming beyond the Thames-side wharves is an albumen print from a wet collodion negative, virtually identical to a calotype photograph taken before by Alfred Rosling, a timber merchant and one of England's earliest amateur photographers. It is possible that Rosling tried to recapture the scene later using the more up-to-date process.

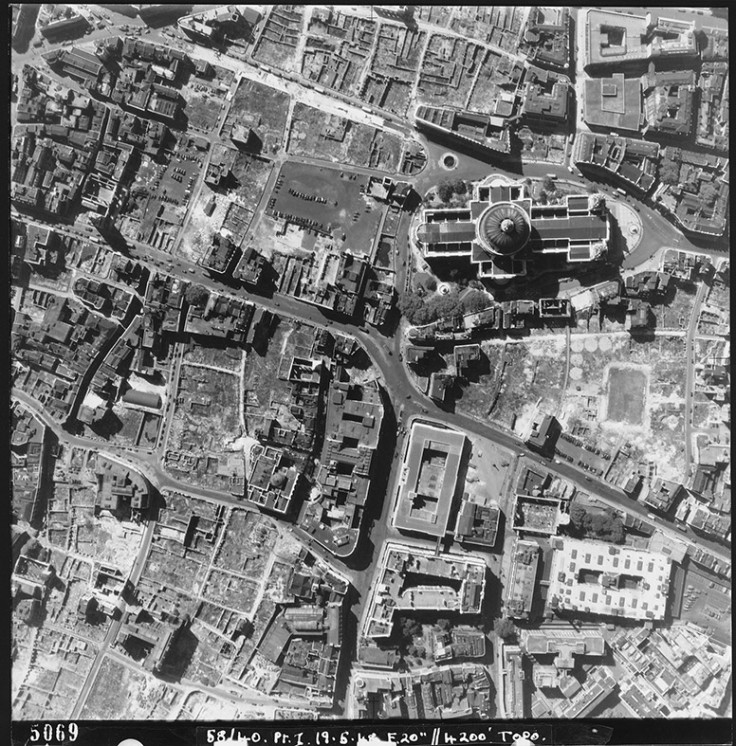

The first photograph in Britain from an aeroplane was probably taken in 1909, but very few were taken in the years before 1914. The First World War demonstrated the crucial value of aerial reconnaissance photos. Britain's first commercial aerial photography company Aerofilms proved so successful that Winston Churchill personally requested the company to form a new intelligence unit briefed to carry out aerial surveillance across enemy lines during WW2.

This view at a scale of 1:2500 shows in graphic detail the extent of the damage inflicted on the City of London during the Blitz. It also demonstrates the economic stringency of the post-war years, with much of the area around St Paul's Cathedral still consisting of cleared bombsites three years after the end of the war. The RAF produced these vertical aerial photographs during a post-war survey programme, covering the whole country at a scale of approximately 1:10,000, and built up areas at larger scales.

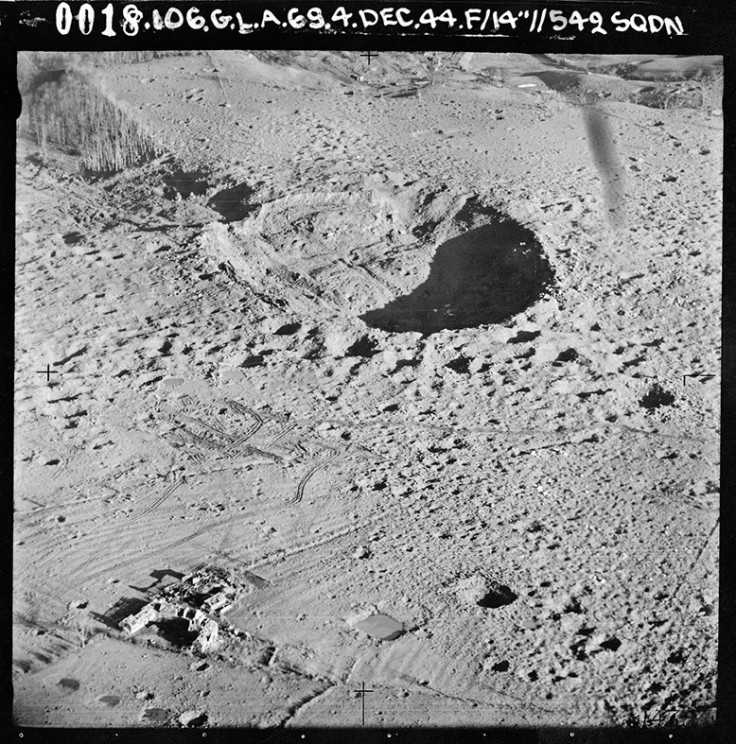

This RAF photograph was taken days after the largest-ever explosion on British soil. Just after 11am on Monday 27 November 1944 more than 3,500 tons (3,175 tonne) of ordnance exploded and destroyed part of an underground RAF munitions store near Fauld in Staffordshire. A store worker is thought to have used a brass chisel to remove a detonator from a live bomb, and so caused a spark. About 70 people were killed, including nearby workers as well as staff at the dump. Hanbury Fields Farm (bottom left) was badly damaged. The huge crater, 250m across, is still very visible in the landscape.

The evolution of specialist architectural photography in the late 19th and early 20th centuries coincided with a period of extensive urban growth and

redevelopment. Grand Victorian buildings and engineering projects were documented to display wealth and confidence at the height of the Empire.

The image below is one of a series of images taken by Henry Dixon to record progress on the Holborn Viaduct construction. It shows the scale of a project which involved demolishing more than 4,000 buildings and provided a causeway over the Fleet Valley, connecting the West End with the City.

The Thames embankment formed part of the scheme designed by Joseph Bazalgette for the Metropolitan Board of Works to construct a modern sewage system for the capital. Work had begun in January 1859, and the section south of the River Thames was completed in 1865; the northern section ten

years later.

Construction of the Rotherhithe tunnel began in 1904. The road tunnel connected the dock areas of the Ratcliffe district of Limehouse north of the Thames with Rotherhithe in the borough of Southwark to the south of the river. The Prince of Wales, later King George V, officially opened the tunnel on 21 June 1908.

Sydney Newbery captured this photo of lift attendants at Selfridges department store posing with military precision. The photograph was taken at around the time that the store's western extension was completed.

The accelerating pace of change since Victorian times has eroded the country's traditional streetscapes, landscapes and ways of life. Great Britain, unlike France, was slow to create a state-sponsored programme to protect and record the historic environment. It was left up to concerned individuals to fill the gap, forming groups of like-minded people who tried to protect landscapes and historic buildings. The pressure that they put on governments encouraged the gradual evolution of nationwide programmes to record and care for historic monuments.

Bristol's Steep Street existed in the medieval period when it was the main road from the centre of Bristol to Gloucester. In 1871, this historic thoroughfare was demolished in the name of progress and replaced by a modern road. This photograph of the charming old curved street, taken in 1866, was published in 1891 as a nostalgic view by Bristol art publishers and print sellers Frost & Reed. A limited run of 100 prints was produced and the negative destroyed.

In 1882, the state began to assume responsibility for the protection and care of the nation's historic monuments, although the Ancient Monuments Protection Act was initially largely concerned with prehistoric monuments such as stone circles.

After many years in private ownership, Stonehenge was given to the nation in 1918. A programme of restoration followed a structural survey by the Office of Works. The archaeologist Lieutenant-Colonel William Hawley supervised extensive works that included excavation, the righting of fallen stones, and remedial steps to prevent the collapse of others. Here a trilithon lintel is being replaced following the re-erection and setting in concrete of Stones six and seven.

Monkton House was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and built for William James in 1902, but this view of the staircase shows the striking result of the alterations and redecorations carried out by James's son, Edward, from the 1930s onwards. Edward James was a patron of the arts, and the foremost English supporter of Surrealism. He was particularly influenced by Salvador Dali. The Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England generally recorded sites threatened by proposals to demolish or alter the existing fabric, but photographic coverage here recorded the contents of the house in the Surrealist-influenced interior before they were sold at auction.

Picturing England: The Photographic Collections of Historic England by Mike Evans, Gary Winter and Anne Woodward is out now (Historic England, £45). To tie in with its publication, a free exhibition of the images from will run from 1 July to 21 September at The Library of Birmingham.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.