History told us not to ignore how furious people are at the elite – but we didn't learn

Globalisation has been extraordinarily beneficial but, while some race ahead, others are being left behind.

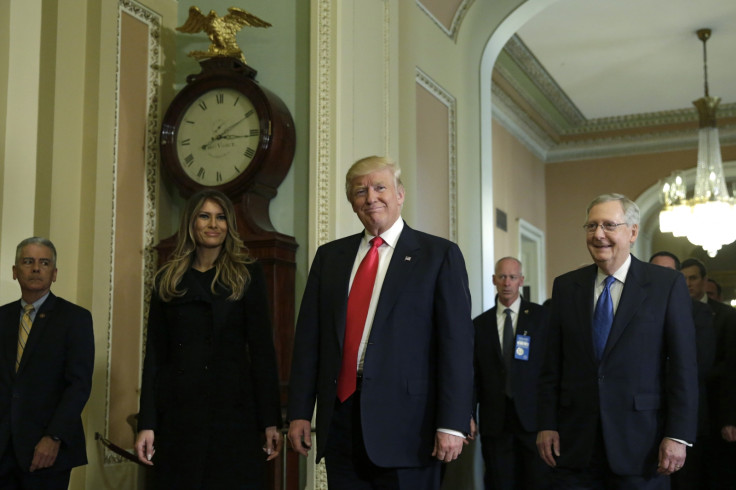

Donald v Hillary felt unique, but their battles echoed those of the Renaissance – as did Brexit. By failing to learn from history, polls and experts underestimated the groundswell of discontent.

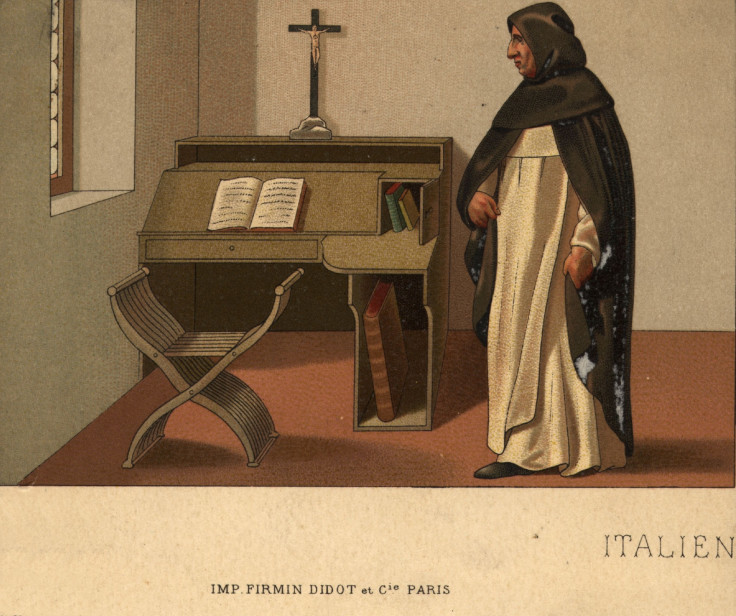

Donald Trump is a fundamentalist. His improbable presidential run followed closely the script set forth by the chief doomsayer of the Renaissance, Girolamo Savonarola. A political outsider, Savonarola exploded from obscurity in the 1490s to captivate the city of Florence and overthrow the Medici establishment that had made Florence the most advanced city in the world.

How did Savonarola do it? First, by shouting an apocalyptic message that stoked people's deep anxieties. Ottoman Muslims loomed to the east. The authorities were corrupt. Globalisation benefited only the well connected and brought new diseases and risks for the masses.

Second, he owned the news cycle. Print media was just emerging, and Savonarola harnessed its potential better than any. His fiery sermons rolled off the newly introduced printing presses, and just as Trump has used social media to confound the traditional media, Savonarola used one page pamphlets to circumvent the popes and princes who previously had monopolised information flows.

Third, he believed in himself above all others. God had appointed him to bring a better tomorrow.

The Renaissance was a time of tumultuous change. Those able to benefit from innovation and the voyages of discovery became fabulously wealthy, but the majority were left behind, not least the scribes and traders that were left without livelihoods by progress.

Savonarola understood that when societies change fast, people get left behind more rapidly. And when the fortunate few get fabulously wealthy, resentment and anger brew.

That citizens in America and Europe are angry with authority is not a surprise. The banking elite, aided and abetted by the central banks and treasuries of the world brought us the financial crisis, while the well paid international guardians of financial stability at the IMF, BIS and elsewhere looked on.

In the USA and Europe, the middle class has seen a stagnation of incomes while the super rich have claimed a greater share of wealth. Notable global companies avoid taxes, while governments that seek to attract them succumb to a race to the bottom.

Globalisation has been extraordinarily beneficial in many ways. But as in the Renaissance, what the politicians have failed to appreciate or address is that while some race ahead, others are being left behind. And that while unprecedented benefits have come from globalisation, not least in lifting billions of people in developing countries out of poverty, this is cold comfort for citizens in the advanced countries that feel more vulnerable and anxious as they witness accelerating change, growing inequality and rising uncertainty.

Brexit confounded the experts that confidently and correctly consider that it will be bad for the British economy and British workers. Yet the parts of Britain which are the most dependent on the European Union – such as Sunderland, the home of Nissan exports to Europe – or Cornwall and Wales, which receive significant EU agricultural subsidies - were virulently against Brussels. The anger was not identified by the pollsters who failed to capture the Brexit swing. Nor did they understand the dangers arising from the failure of the deeply unpopular Labour leader Corbyn to articulate a compelling vision for Remain.

By defining himself as the anti-establishment candidate, Trump made a virtue of his ability to defy the experts and the establishment media. The more they attacked him, the more he was able to define himself as anti-establishment and the friend of those citizens who felt betrayed by government and the Wall Street and Washington elite. As with Brexit, the polls underestimated the extent of anger at authority. And as with Corbyn, Clinton failed to inspire hope in the future, and could not distance herself from the elite with who she has been intimately associated.

The lessons need to be learnt. We ignore the legitimate concerns of those left behind at our peril.

Ian Goldin is Professor of Globalisation at Oxford University and former Vice President of the World Bank. Chris Kutarna is a fellow at the Oxford Martin School. Their new book, Age of Discovery: Navigating the Risks and Rewards of Our New Renaissance, is published by Bloomsbury.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.