HIV is Mutating to Adapt to Humans Warn Scientists

HIV is slowly adapting within its human hosts, scientists in Canada warn in a newly-published study. Although it is believed the rate of evolution is too slow to have an impact on the design of vaccines to fight HIV there is concern that in areas of the world hardest hit the rate of adaption may be more pronounced.

The research was done by scientists from the Faculty of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia and published in the journal PLOS Genetics. The team reconstructed the epidemic's ancestral HIV sequence since the first recorded cases in 1979, which enabled them to assess the spread of immune escape mutations.

Most research into HIV - Human Immunodeficiency Virus – focuses on how the virus adapts to anti-viral drugs. This study wanted to discover how HIV adapts to humans, explains lead author of the study Zabrina Brumme:

Transmitted immune escape mutations could erode our ability to naturally fight HIV

"HIV adapts to the immune response in reproducible ways. In theory, this could be bad news for host immunity – and vaccines – if such mutations were to spread in the population. Just like transmitted drug resistance can compromise treatment success, transmitted immune escape mutations could erode our ability to naturally fight HIV."

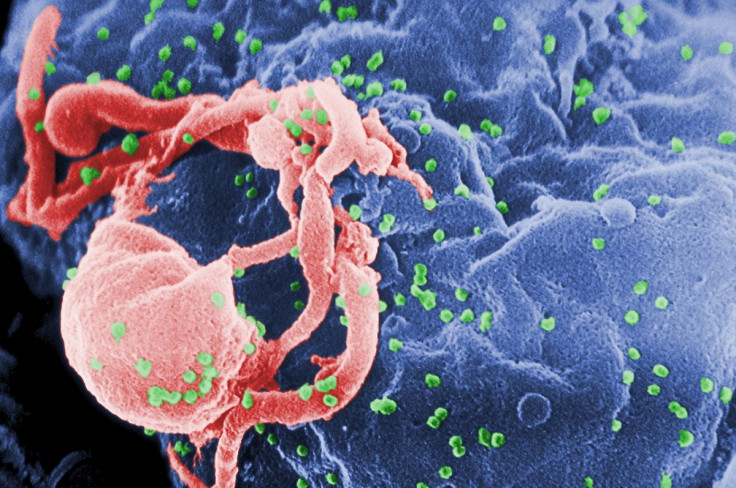

HIV weakens the body's immune system by destroying CD4 cells. If enough CD4 cells are destroyed you can develop full-blown AIDS. To date, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimate at least 36 million people have died from the epidemic.

The origins of HIV are disputed, with many scientists believing it originated in Africa at some point between the late 1800s and the 1950s, possibly as a result of a human eating "bush meat" – probably a chimpanzee. Today Africa has far higher rates of HIV and AIDS, and report author Brumme warns the virus may evolve more rapidly in such an environment.

"Overall, our results show that the virus is adapting very slowly in North America," says Brumme.

"In parts of the world harder hit by HIV though, rates of adaptation could be higher. We already have the tools to curb HIV in the form of treatment – and we continue to advance towards a vaccine and a cure. Together, we can stop HIV/AIDS before the virus subverts host immunity through population-level adaptation."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.