HIV: Researchers May Have Found The Trick to Slow Down or Even Halt Virus

The region of the DNA to which the HIV virus binds itself is what determines how quickly the disease progresses, says a new study.

By retargeting the integration site to a 'safer' part of the host DNA, new therapies for Aids can be developed.

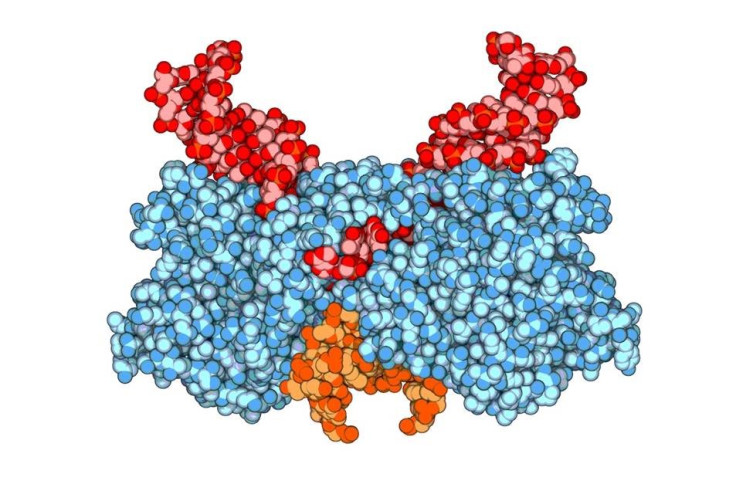

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) binds and invades human immune cells where it reprogrammes the human DNA to produce new HIV. The HIV protein integrase plays a crucial role by identifying a segment of the host DNA and orchestrating the manipulation of the DNA.

While the viral DNA can be inserted at many places on the strand, how it picks certain sections has been unknown.

Proteins are long chains of amino acids. In the viral integrase, the researchers found two amino acids that determine the integration site.

KU Leuven researcher Jonas Demeulemeester, first author of the study, explains: "HIV integrase is made up of a chain of more than 200 amino acids folded into a structure. By modelling this structure, we found two positions in the protein that make direct contact with the DNA of the host. These two amino acids determine the integration site. This is not only the case for HIV but also for related animal-borne viruses."

By replacing these amino acids by those of other animal-borne viruses, they saw that the viral DNA integrated into the host DNA at different locations.

The study also showed that the viral protein in HIV can vary with different amino acids appearing in the positions.

Most important, the work showed rapid progression of Aids when they changed the integration site.

The study by KU Leuven's Laboratory for Molecular Virology and Gene Therapy and University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa was published online in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

The fast mutating HIV has eluded a cure despite many claims in the recent past. The latest is the case of two men infected years ago who never developed Aids and have undetectable levels of HIV.

The virus was inactivated because its genetic code had been altered, said the researchers linking this to increased activity of a common enzyme Apobec. However, experts have questioned the accuracy and quality of the research, reports Newsweek.

While cocktail drugs have been able to slow down the virus or keep it down to low levels, no treatment has effectively cured anyone of Aids, as the virus has managed to stay one step ahead and hide somewhere before surfacing at a later time.

The longest time a person has remained healthy and seemingly free of HIV after infection is five years. Timothy Brown, who received a bone marrow transplant from a person genetically resistant to the pathogen, remains HIV-free five years after the treatment.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.