Hong Kong protesters seek sanctuary overseas as noose tightens

The current trickle could become an exodus after Beijing announced plans to impose a sweeping national security law on Hong Kong in response to the protests.

Hong Kong protester Crystal has yet to tell her parents she has fled overseas to seek asylum in Canada, one of a growing number of residents choosing self-exile as Beijing tightens control.

The 21-year-old student spent months on the front lines of the pro-democracy protests, which first exploded with huge marches last June and descended into increasingly violent battles with riot police as each month went by.

A year on, she is waiting to hear if she will be granted refugee status on the other side of the world.

"My friends and family don't know about my situation," she told AFP, asking for her full name and location to be withheld -- like all applicants interviewed for this piece.

"They all thought I went to study abroad."

Activists in Canada say at least 50 former Hong Kong protesters lodged asylum applications before the coronavirus pandemic ended most international travel.

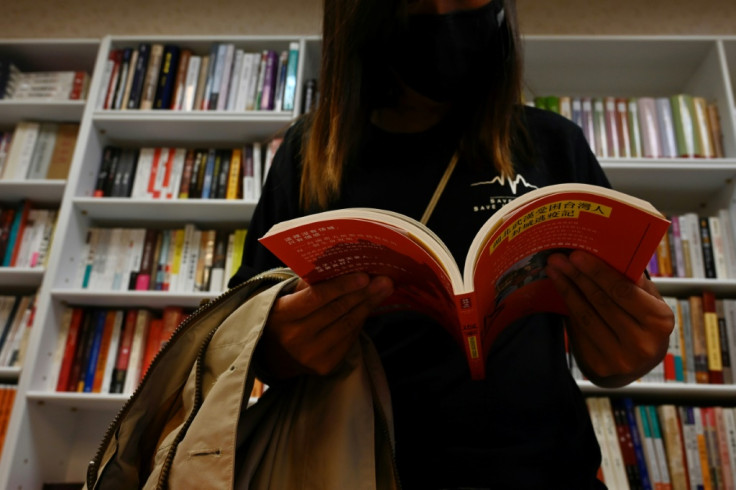

Hundreds more have relocated to democratic Taiwan, which under President Tsai Ing-wen has said it will try to accommodate Hong Kongers seeking to escape with freedoms sliding at home.

The current trickle could become an exodus after Beijing announced plans to impose a sweeping national security law on Hong Kong in response to the protests.

China says an anti-subversion law is needed to tackle "terrorism" and "separatism".

Opponents fear it will bring mainland-style political oppression to a business hub supposedly guaranteed freedoms and autonomy for 50 years after its 1997 handover to China by Britain.

In response, Britain has said it will extend residency rights for 2.9 million Hong Kongers eligible for British National (Overseas) passports, including a possible pathway to citizenship.

The documents are only available to those born before the former colony's 1997 handover. Which means younger residents -- the vanguard of last year's protests -- must risk asylum instead.

The concept of a Hong Kong asylum seeker is somewhat untested -- for decades the city was a place people fled to rather than from.

But there is one precedent.

Last year, Germany granted sanctuary to two independence activists wanted for their involvement in a violent protest in 2016.

It was the first time a western government decided Hong Kong dissidents were fleeing persecution and the move infuriated Beijing.

Canada has emerged as a favourite destination, aided by a network of activists who have helped people escape Beijing ever since the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown.

"Canada is always a country that welcomes refugees," said Martin, a member of the New Hong Kong Cultural Club which is currently helping 29 applicants.

"We believe there will be more Hong Kongers seeking asylum in Canada because the Hong Kong situation is falling into chaos."

Richard Kurland, a veteran Canadian immigration lawyer, said asylum claims would be decided on a case by case basis.

"An 'over the top' reaction by either Beijing or the local Hong Kong proxies would strengthen the case for bona fide refugee claims in Canada," he told AFP.

Asked whether plans for the new security law might constitute such a reaction, he replied: "It will all turn on the details of the new law, and how it is implemented."

Canada's asylum cases are decided by an independent tribunal, not the government.

But refugee claims could further strain already frosty ties with Beijing after Canada acted on a US arrest warrant for Meng Wanzhou, a top executive at Chinese tech giant Huawei.

Bonnie Glaser, an expert on China with the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said cooperation between western nations would make it harder for Beijing to respond.

"If one country acts by itself, it is possible that Beijing will try to impose punishment to deter other countries from doing the same: killing the chicken to scare the monkey," she said, using a popular Chinese idiom.

Those fleeing abroad face an uncertain future in an unfamiliar land.

Ah Gor, a graphic designer in his early thirties, arrived in Canada after he was charged with rioting, an offence that carries up to 10 years jail.

"Hong Kongers are unable to fully exploit their potential because we are forcibly fused together with the totalitarian Chinese state," he told AFP, saying he now supports independence, a red line for Beijing.

As someone who studied overseas, language has not been an issue.

But he has struggled with the Canadian winter: "Never in Hong Kong had I experienced temperatures that left my skin in pain."

Taiwan offers potential sanctuary closer to home, although it comes with caveats.

The island has no refugee law so most Hong Kongers must seek business and student visas.

Beijing also views the self-ruled island as its own territory, vowing to one day seize it, by force if necessary.

Xiao Hua, a 35-year-old registered nurse, worked as a medic during the early stage of the 2019 protests, has spent the last few months in Taiwan and is considering a full-time move.

"I feel Taiwan is a place where we can still voice our opinions freely," she told AFP inside a restaurant in Taipei that finds employment for Hong Kongers.

"It will be unbearable, to leave my family, my friends in Hong Kong. But freedom is a very important thing to me."

Copyright AFP. All rights reserved.

This article is copyrighted by International Business Times, the business news leader