Housing Bill stalls as government warns 'unelected' peers not to trample on its mandate

Time is running out for the government to pass the controversial Housing and Planning Bill amid a stalemate between MPs and peers who cannot agree on a final draft of the legislation. The Housing Bill is in a status called "ping pong" where it travels back and forth between the two houses until a text can be agreed and sent off for royal assent, when it becomes law.

Ministers want the bill to pass before the state opening of parliament on 18 May when the government will move on to next year's agenda. If the bill fails to pass, it must be reintroduced and start its journey again through parliament. The government said it is listening to points made by the bill's critics.

Peers defeated the government on 13 amendments to the Housing Bill watering down several key policies, including discounted starter homes for first-time buyers and "pay to stay" which will see higher-earning council tenants pay market rents. But the Commons voted down these amendments, sending the bill into ping-pong.

Despite the delays, Labour's shadow housing team still believes the bill will pass before the looming deadline, but both the Lords and the government must make further concessions and meet in the middle.

"Our landmark Housing and Planning Bill will help us boost home ownership and we remain committed to delivering the homes that this country needs," a spokesman for the Department for Communities and Local Government (DCLG) told IBTimes UK. "We're listening carefully to points raised in debates and from the sector."

Baroness Williams of Trafford, a DCLG minister in the Lords, told peers she hoped amendments accepted by the Commons and passed back to he Lords would be sufficient. "We have a clear mandate to deliver 200,000 starter homes and to improve housing delivery," she said.

While the government is making some small concessions, it has invoked its financial privilege in the Lords to knock down some of the amendments. This is a convention in parliament where peers do not vote against the government if doing so will interfere with budgetary or financial matters. There was controversy at the end of 2015 when, despite the government invoking its financial privilege, peers voted down a package of cuts and reforms to the tax credits system.

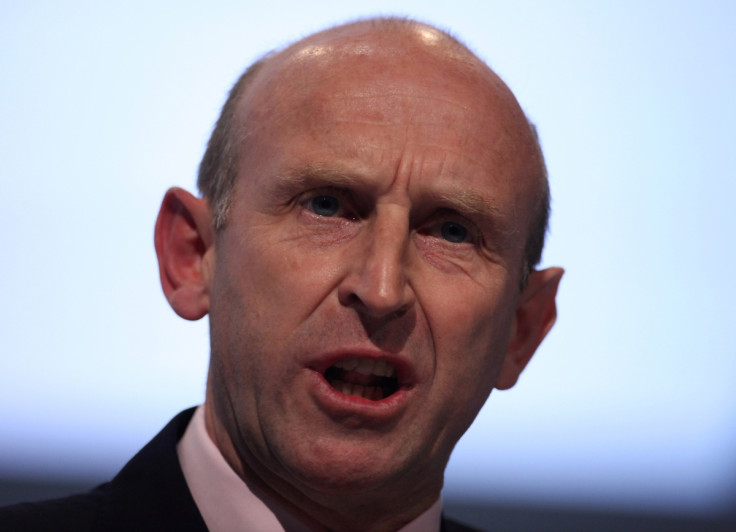

Housing Minister Brandon Lewis made some technical compromises to the bill before it was sent back to the Lords. While opposition peers noted the government's movement on policy, the Lords did not agree to the Commons' latest amendments, sending the bill back to MPs again after their session on 4 May with new compromises. On Twitter, Lewis bemoaned "unelected" peers for blocking his bill.

One example is disagreement over how much more rent higher earners should pay if they live in council homes. The government has already agreed with peers that there should be an incremental rise above the proposed earnings threshold, but the details are yet to be agreed. Pay to stay is intended to create a fairer deal for taxpayers by making those who can afford to pay market rents for living in council-owned housing.

The government suggested that for every pound over the household income threshold — £30,000 outside London and £40,000 inside, though peers want these both £10,000 higher — the rent should rise by 20p. But peers knocked this back, suggesting a 10p rise for the first £10,000 after the threshold and 20p above that. Now the government is proposing a 15p taper for all higher earners, with the threshold rising every year with inflation.

On pay to stay, the additional money raised from higher rents will go directly to the Treasury rather than the local council, so the government used its financial privilege. "We are hearing a good deal today about financial privilege as the government are deploying a tactic of pleading it as a reason to reject amendments passed in this house," Lord Beecham of Labour told peers.

"The words must sound ironic to couples on the national minimum wage, who are deemed to be 'financially privileged' if their household income exceeds £30,000 outside London or £40,000 in it, and therefore face, as we have heard, increases in their non-subsidised rent.

"They will no doubt contrast their position with the financial privilege extended to starter home buyers, who stand to benefit from discounts of more than £80,000 in London on the more expensive houses and tax-free capital gains when they eventually sell."

On starter homes, peers want local councils to have the authority to determine how many are built in their areas. Councils are hostile to starter homes, which the government believes should be classed as "affordable", because they think developers will build fewer homes for affordable rents as a consequence, chasing profits from starter homes instead. Giving them the power to decide how many are built would effectively kill off the policy.

There is now a back-and-forth between the Commons and the Lords on this issue. Each side is giving way on small concessions. The Lords is pushing to weaken the power of the secretary of state to overrule local councils and force through the construction of starter homes, and the government is seeking to retain an ability to get much-needed new housing built.

"It is a ground-breaking move to require that starter homes will be built on all reasonably sized and viable sites, but it is necessary and justified to ensure that these homes are delivered, and delivered soon," said Baroness Williams, citing the government's target of building 200,000 starter homes by 2020.

"We cannot wait for each of the 336 planning authorities to undertake local needs and viability assessments before action on starter homes is taken; given that 30% of councils have not adopted a post-2004 plan, the risks to delivery are simply too high."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.