How the 2011 Japanese tsunami flung hundreds of marine species across the Pacific to the US West Coast

Researchers describe the event as the biggest, unplanned, natural experiment in marine biology history.

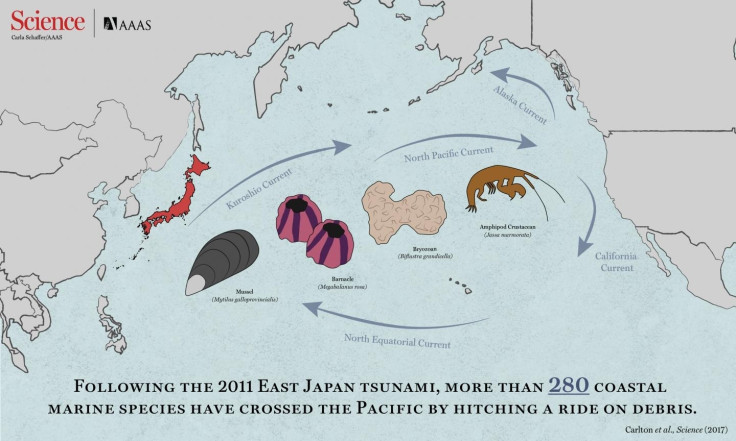

Following the powerful Japanese tsunami in 2011, which devastated the country's East Coast, an unprecedented migration of animals occurred. According to new research, nearly 300 species of marine animals hitched a ride on debris thrown into the ocean by the destructive wave, appearing years later on Hawaii and the West Coast of America.

The tsunami - which was triggered by the fourth most powerful earthquake ever recorded - killed more than 15,000 people and caused more than $200 billion of damage, as well as sparking a nuclear accident at the Fukushima power plant. At some points, the tsunami wave was reported to be more than 125 feet tall.

Amidst the destruction, millions of objects were swept out to sea including small pieces of plastic, fishing boats, buoys and crates. Many animals latched on to these objects in what would turn out to be the beginning of an epic journey across the hostile waters of the Pacific Ocean.

Surprisingly for the researchers, many of these coastal animals survived the trip, which could have taken many years. In fact, some of the animals survived at sea for four or more years longer than any previous observation of creatures found on so-called "ocean rafts."

The study, which also shows how marine debris could act as a novel vector for invasive species, is published in the journal Science.

"I didn't think that most of these coastal organisms could survive at sea for long periods of time," said Greg Ruiz, a co-author and marine biologist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. "But in many ways they just haven't had much opportunity in the past. Now, plastic can combine with tsunami and storm events to create that opportunity on a large scale."

Scientists first noticed animals washing up in Hawaii and North America when the first tsunami debris arrived in 2012. And by 2017, when the study came to an end, they had documented 289 different species of marine animals.

Many of the animals found were molluscs, worms, crustaceans or hydroids – small predatory creatures related to jellyfish. Nearly two-thirds of the species were unknown on the US West Coast, and none were thought to have been capable of surviving a transoceanic voyage. This is because the open ocean is a much more hostile environment for animals that are used to more hospitable coastal waters.

However, the researchers speculate that because ocean rafts move so slowly – 1 or 2 knots as opposed to around 20 for commercial ships – the animals were able to gradually adapt to their new environments. Some species may even have found their new surroundings to be beneficial for reproduction because their larvae could attach to the debris.

At present none of the new animal arrivals are known to have colonised the West Coast, although it can be years before an established population of a non-native species is detected. Researchers say the full consequences of the tsunami with regards to its impact on native animal populations in the US is still uncertain.

"This has turned out to be one of the biggest, unplanned, natural experiments in marine biology, perhaps in history," said John Chapman, co-author of the study from Oregon State University.

"One thing this event has taught us is that some of these organisms can be extraordinarily resilient," he said. "When we first saw species from Japan arriving in Oregon, we were shocked. We never thought they could live that long, under such harsh conditions. It would not surprise me if there were species from Japan that are out there living along the Oregon coast. In fact, it would surprise me if there weren't."

In attempting to combat invasive species, which can wreak havoc on native animals, scientists largely agree that prevention is effective strategy. Since preventing tsunamis is clearly not an option, the focus should be on managing plastic, Ruiz says.

"There's an increasing load of plastic and microplastics at sea that are thought to have significant consequences for biology and ecology," he said. "This is one other dimension and consequence of plastics and manmade material that deserves attention."

According to James Charlton, lead author of the study, there is "huge potential" for the amount of marine debris in the ocean to increase significantly.

A 2015 Science journal paper suggested that 10 million tons of plastic enter the oceans every year, a figure which is set to increase tenfold by 2025.

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.