How Cyrille Regis, The Three Degrees and The Specials fought racism in English football

KEY POINTS

- But the Rooney Rule and the Eni Aluko case prove The Football Association still have work to do.

- Regis died on Monday [15 January] aged 59 after spells at West Bromwich Albion and Coventry City.

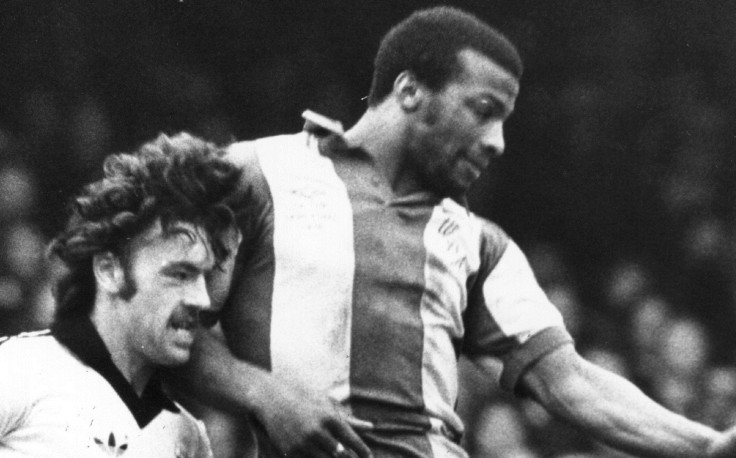

For those who have grown up during the cosmopolitan era of the Premier League, the footballing world that Cyrille Regis inhabited just a few decades ago must seem light years away. Regis, who has sadly passed away at the age of just 59, was at the forefront of sweeping changes in the sport and for a more tolerant and inclusive multi-cultural society.

Born in French Guiana, Regis moved to Britain when he was just five years old, and burst into the English footballing consciousness as part of a new breed of players at West Bromwich Albion. Under manager Ron Atkinson, Regis played alongside Laurie Cunningham and Brendon Batson. While they were not the first black players to feature in England's top flight, their collective development challenged attitudes and perceptions.

They were dubbed 'The Three Degrees' after an all-girl singing group of the same name who just happened to be Prince Charles' favourites. It was an affectionate nickname, given by their manager. Whether it would be considered quite so acceptable nowadays is open to debate, given subsequent developments in language and the fall from grace of Atkinson.

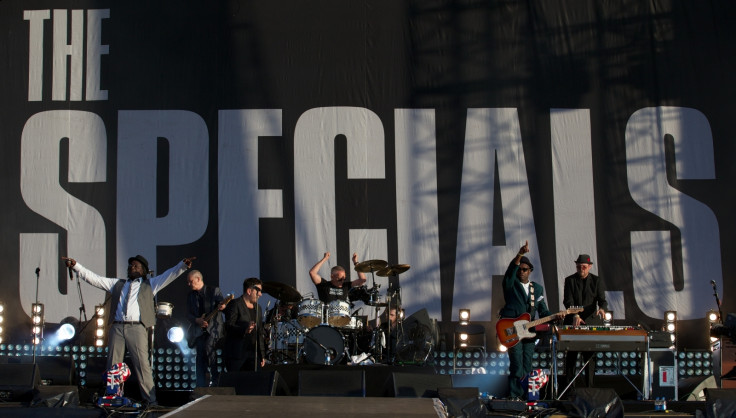

The Midlands, with large immigrant populations in the cities, spearheaded enlightened attitudes in society through the late 70s and 80s. Regis, Cunningham and Batson's glory days at WBA coincided with the growth of the Two-Tone musical movement in the region. As The Specials, The Selecter and others fused musical sounds and trumpeted a multi-cultural society, The Three Degrees did something similar on the football field. They were footballers rather than spokesmen, but their actions spoke louder than words.

This upsurge in multi-cultural tolerance and positivity was partially a reaction to entrenched racism. Enoch Powell's Rivers of Blood speech, attacking mass immigration, had been delivered in Birmingham in the late 1960s but was given new relevance in 1976 by the outspoken support for the politician by rock star Eric Clapton. Two-Tone and Rock Against Racism were in some ways spawned in direct opposition to these reactionary views. English football fans were often similarly reactionary and even more rabid.

Regis and his teammates were frequently subjected to racist abuse from the terraces. Monkey chants and thrown bananas were not uncommon. The abuse they faced came to a particularly ugly conclusion when Regis was awarded his debut cap for England and found a bullet in the mail along with the message: "If you put your foot on our Wembley turf you'll get one of those through your knees." The striker kept the bullet and later said in his autobiography: "The more abuse I received, the more I channelled my anger into my performances."

The news of Regis's untimely death has brought an outpouring of tributes from footballers who know that their lives were easier because of the hard yards put in by the physically-imposing centre forward. Former Manchester United striker Andrew Cole called him "my hero, my pioneer, the man behind the reason I wanted to play football". Player-turned-pundit Mark Bright described Regis as "an inspiration to myself and many players of my era – he blazed a trail for every black player who followed him".

Of course Regis's 158 goals (mostly for WBA and Coventry City) and his five England caps did not bring an end to racism in football. Recent allegations against some of Chelsea's managerial staff in the 1990s make for particularly ugly reading even if the charges have been denied.

And The Football Association recently found itself at the centre of claims surrounding the racial discrimination Eni Aluko and Drew Spence experienced during Mark Sampson's time as England Women's manager.

The FA is keen to be seen to be leading the fight against racism and has just introduced the Rooney Rule, which aims to tackle institutional racism in the sport by interviewing at least one candidate from an ethic minority for all jobs in the England set-up.

Named after a former owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, the Rooney Rule has had some success in challenging ingrained prejudices by requiring NFL teams to interview black, Asian and minority ethnic candidates for senior coaching roles. But The FA has its work cut out: there are currently just five BAME coaches across the 92 football league clubs.

Racism and prejudice still exist and the fact that football's governing body is bringing in this rule 15 years after the NFL suggests there is still a long way to go. But the experiences of Regis and company are hopefully less common for their footballing heirs.

That Regis is being mourned so fondly is a testament to his talents on the field and his stoicism off it. Regis's pace, power and good humour won many personal admirers during his career and helped challenge attitudes which had gone on for far too long. He has not died in vain.